Huntington’s disease (HD) has long been impossible to cure, but new research is finally giving fresh hope. HD is a progressive, hereditary brain disease that affects movement, cognition and emotions. Doctors often diagnose HD when people show clear movement problems, typically around 30-50 years of age, after which patients live about 15-20 years.

The global prevalence of HD is about five per 100,000 people. While it is not as prevalent as Alzheimer’s disease, the disease starts much earlier in life, often when people are still in work and raising families.

Sadly, there is no cure. But a couple new research papers, by our team and others, suggests this may be about to change.

The causes of HD long remained a mystery since it was discovered in the 19th century. But in 1993, researchers uncovered that HD is caused by repetitive expansions of three DNA letters (C, A and G) in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene, resulting in the production of a mutant huntingtin protein.

This gene normally has a section that repeats the letters CAG over and over. In healthy people, the repeat is lower than 35. Repeat lengths greater than 39 will result in HD. The more repeats you have, the earlier symptoms usually start. In addition to your inherited CAG length, this sequence tends to continually expand in certain cells over a person’s lifetime, known as somatic expansion.

At the time, in 1993, the discovery generated lots of excitement. First, you could identify which relatives in a family with a history of the disease would develop it. Those of us working in HD clinics at the time were highly concerned about the ethical and mental health issues this also raised. There was a big need for counselling, for example. Second, it was thought, somewhat mistakenly, that very quickly there would be a treatment.

Many studies have investigated people with the HD gene expansion 15 years before onset and some even as far as 25 years before onset. Even before the onset of movement problems, changes in cognition, mood and the brain have been found.

Samurai Cat/Shutterstock

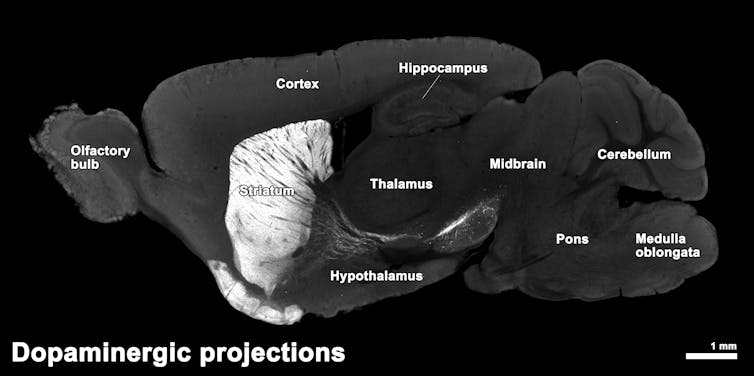

In particular, the brain changes start in a part called the striatum, which helps control movement. Here, certain nerve cells (called GABAergic medium spiny neurons) die off. As HD gets worse, damage spreads to other areas like the cortex, which are important for cognition, and white matter, which connects brain regions.

Progress at last

Only recently has there been some promising results in the treatment of HD by clinical researchers Sarah Tabrizi and Edward Wild at University College London. Although, the research is still waiting to be peer reviewed and published, the results have been reported in a press release by uniQure, a US biotechnology company.

In this trial, a gene therapy, AMT-130, that reduces the production of the toxic mutant huntingtin protein was given to 29 HD patients with a definitive clinical diagnosis, between the ages of 25 and 65. The results showed slower cognitive decline on standard neuropsychological tests, particularly in processing speed and reading ability. Most significantly for doctors, cerebrospinal fluid levels of a protein called neurofilament light, a general marker for neurodegeneration, were reduced after three years follow-up, even below baseline levels.

This indicates that the therapy may actively protect brain cells from damage rather than simply masking symptoms. It is hoped that, in future, it will be possible to provide safe and effective treatments at earlier stages of the disease. Hopefully, people with the HD gene expansion will have improved cognition and emotion and reduced motor symptoms, which will improve quality of life and may even extend their lifespan.

This was a motivation for our new work, a collaboration between UCL and the University of Cambridge, for the HD- Young Adult Study. The study recruited 131 people: 64 with the HD gene expansion and 67 controls, long before predicted disease onset, approximately 24 years. The study gathered in-depth information about participants’ cognition, mood and behaviour, alongside brain scans and tests of blood and other fluids that can show how healthy their brain cells are.

At this early stage, we noted some increases in markers of neurodegeneration with limited effects on brain volume and cognition. Given that the striatal circuits are disrupted early in HD, we wanted to determine whether cognitive flexibility, how easily people can swap between different approaches and perspectives, a function that relies on this circuitry, was affected at this very early stage in those with HD gene expansion.

Indeed, we showed some mild early disruption to cognitive flexibility, which was associated with alterations in the connectivity in these circuits. This cohort was also followed up about 4.5 years later, where changes in many measures became more apparent.

Importantly, in collaboration with the University of Glasgow, we showed that somatic expansion, how the CAG sequence tends to continually expand in certain cells over a person’s lifetime, can give crucial information. This study was the first to show in living humans the faster this somatic expansion, the faster the disease progresses. This can explain why some people who have identical inherited CAG length in the Huntingtin gene can still have different onset of the disease.

Cognitive deficits were apparent at this time, although they were in a specific cognitive process. Our findings reveal early sustained attention deficits in people with expanded CAG sequences, which are associated with changes in brain circuits in the inferior frontal gyrus (involved in attention) well before movement was affected.

Intriguingly, this brain area is also linked to the inability of people with ADHD, to focus their attention, as we discovered in an earlier study. This suggests that this disruption in sustained attention in HD may reflect a neurodevelopmental process rather than a neurodegenerative one at this early stage of the disease.

These findings suggest that there is a treatment window, potentially decades before motor symptoms are present, where those with the HD gene expansion are functioning normally despite having detectable measures of subtle early neurodegeneration.

Identifying these early markers of disease is essential for future clinical trials in order to determine whether a treatment is having any effect and preserving the quality of life. In addition, as drugs that slow the worsening of the disease rather than treat the symptoms, are approved by the regulatory bodies for HD, they could be implemented at an early stage to improve quality of life and wellbeing.

We hope that these now rapid advances in the understanding and treatment of HD will, in the near future, bring great benefits to patients.

![]()

Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian receives funding from the Wellcome Trust. Her research work is conducted within the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Mental Health and Neurodegeneration Themes. She is a co-inventor of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB).

Christelle Langley receives funding from the Wellcome Trust. Her research work is conducted within the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Mental Health and Neurodegeneration Themes.