On April 27 2024, near the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, a touring bus was blocked, sprayed with water pistols, and a banner bearing the slogan “let’s put out the tourism fire” was stuck to its front. It was a headline-grabbing protest against the stranglehold tourism holds over the city, and underscored growing tensions between touristification processes and an increasingly vocal local backlash.

Large-scale protests have made Barcelona synonymous with social resistance to the negative impacts of predatory and extractive tourism, but it is far from alone: popular destinations such the Canary Islands, Málaga, and the Balearic Islands have all seen massive protests against the excesses of tourism over the last year.

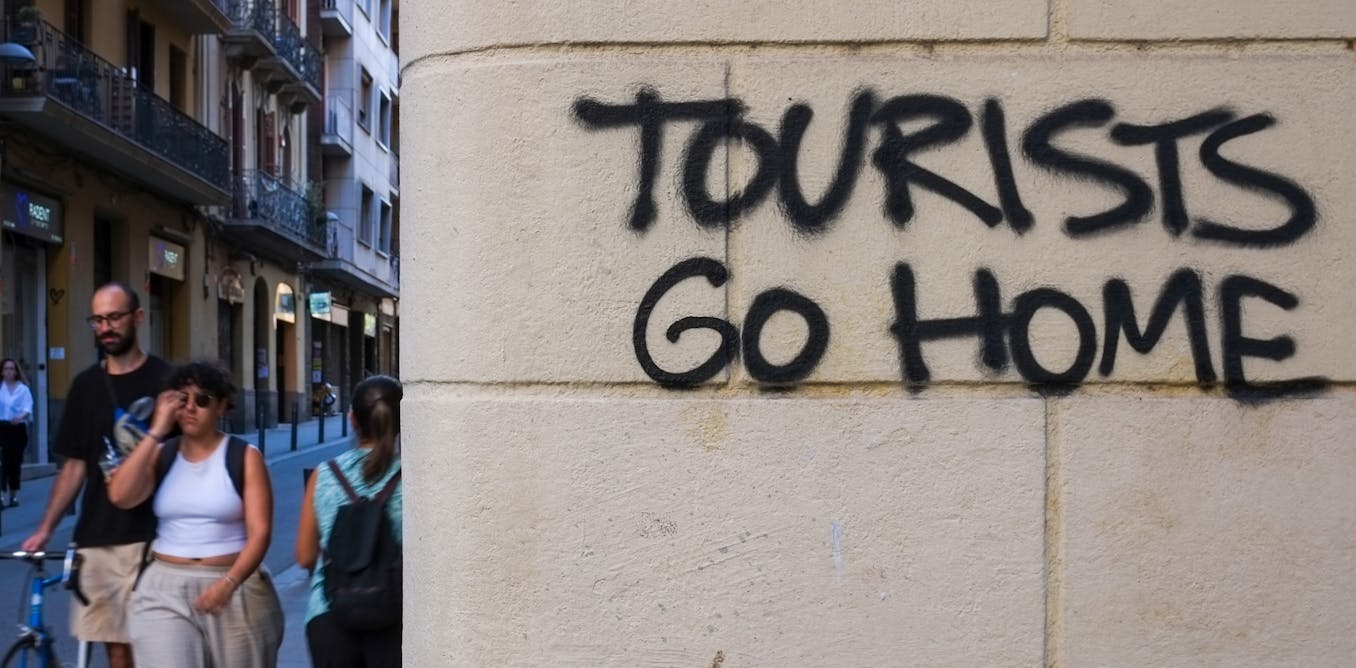

People are fed up, and the writing is quite literally on the wall – tourist apartments graffitied with the slogan “tourists go home” have now become an almost ubiquitous sight in many Spanish cities. However, it is not individual tourists that are to blame, but rather the excessive reliance on tourism which has, over several decades, gradually pushed countless residents out of their homes and neighbourhoods.

But how did we get here? As international travel rebounded in the wake of COVID-19 lockdowns, Barcelona and other Mediterranean cities saw tourists return in remarkable numbers. This led to mounting social unrest, as local communities became increasingly frustrated with how tourism has reshaped urban spaces at their expense.

Nicolas Vigier

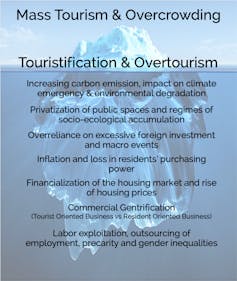

Residents’ concerns range from housing shortages and job insecurity to environmental damage. The privatisation of public spaces is also high on the agenda in Barcelona, exacerbated by high-profile events, such as the 2024 America’s Cup and Formula One Grand Prix, which brought little benefit to local residents.

The ongoing backlash signals a “we’ve had enough” moment that can no longer be dismissed as mere inconvenience or NIMBYism. Instead, it reflects structural inequalities and deeper conflicts over urban space, social justice, and the power dynamics that underpin the tourism sector’s unchecked growth.

Read more:

Overtourism: a growing global problem

Evolving activism

Anti-tourism activism in Barcelona traces back to the mid-2010s, when neighbourhoods like Barceloneta first challenged tourism’s role in displacing residents. Since then, groups such as the Neighbourhood Assembly for Tourism Degrowth (ABDT) have pushed back against policies fostering excessive reliance on the tourism economy.

The ABDT notably prefers the term “touristification” to “overtourism”. According to them, the concept of “overtourism” risks depoliticising the issue, framing it as a simple problem of too many visitors. Instead, they say, the problems are a result of the structural inequalities tied to capitalist accumulation, tourism’s extractive nature, and a sector that funnels community wealth into private hands.

What distinguishes this current wave of activism from its predecessors is a shift from blunt opposition to providing organised, constructive proposals. At one major demonstration in Barcelona in July 2024, activists presented a manifesto calling for clear measures to reduce economic dependence on tourism, and for a transition towards an eco-social economy.

Key demands included ending public subsidies for tourism promotion, regulating short-term rentals to prevent housing loss, cutting cruise ship traffic, and improving labour conditions with fair wages and stable work schedules. The manifesto also urged leaders to diversify the economy away from tourism, repurpose tourist facilities for social use, and develop programs to support precarious workers.

Milano et al. 2024

The movement shows no signs of slowing down. Over the weekend of April 27 2025, exactly one year after the water pistol episode, the Southern Europe against Touristification Network gathered in Barcelona to agree on a shared political agenda. They also convened a coordinated demonstration across multiple cities in Southern Europe for June 15 2025.

Marginalised groups hit hardest

Anti-tourist activism is often dismissed by those with a vested interest in tourism, labelled as either “tourismphobia” or “NIMBYism” – a desire to protect one’s own local area from unwanted development (derived from the acronym of “not in my back yard”).

Milano et al. 2024, Author provided (no reuse)

These labels ignore the fact that tourism-driven economies most strongly impact marginalised groups with little political power, such as tenants, migrants and precarious seasonal workers, and disenfranchised young people. Social movements in Mediterranean cities have taken this to heart, broadening anti-tourism activism to address more general government inaction on housing, labour rights, climate action, and the defence of public space.

These movements confront the complex, interconnected challenges of touristification, including social division of labour, gender inequalities, and capital concentration. They also, importantly, are living proof that many residents want to prioritise community wellbeing over economic growth.

Read more:

Bali gives a snapshot of what ‘overtourism’ looks like in the developing world

Academics and politicians are failing

Both policy makers and academics are falling short in addressing protesters’ concerns. Countless studies focus on topics like space management, green tourism, or tourism as a tool of empowerment. Few, however, explore the experiences of people living in tourism hotspots, or how the sector produces precarious labour conditions, social exclusion and environmental injustice.

As a result, current policies mostly aim at managing visitors or transport, not at curbing tourism’s growth or addressing power imbalances. This limited approach fails to solve the root causes of the problem, and will only perpetuate inequalities.

Beyond urban transformations, tourism’s reliance on precarious labour is a pressing issue. Many jobs in the sector are low-paid, unstable and highly seasonal. While international organisations and cities’ authorities promote tourism as a driver of economic prosperity and job creation, the question of “what kind of jobs?” is too often overlooked.

Going forward, more grounded, intersectional research is needed, especially longitudinal and ethnographic studies that examine the class, gender, and environmental impacts of tourism. This will, in turn, inform policy-making at all levels, and guide it away from the current predatory, growth-first mindset that is fuelling social conflict and inequalities.

Rather than viewing protests as isolated single-issue nuisances, they should be understood as part of broader struggles for social justice. This movement shows that co-constructed alternatives and proposals need to prioritise community wellbeing over economic growth.

Rethinking urban tourism means reimagining cities as places where residents can thrive, not just survive. To achieve this, we must address the deeper inequalities at the heart of touristification processes.