Dr Robert Hawkes, RSPB Conservation Scientist, explains the findings of a recently published article. Here, RSPB and BTO scientists, in partnership with Natural England, explore how much bird-friendly agri-environment management is needed to stabilise or reverse farmland bird declines.

The UK government has recently committed to halting species abundance declines in England by 2030, with similar timebound EU targets currently under discussion. With many species of conservation concern dependant on agricultural habitats, there is a pressing need to rapidly implement effective conservation interventions across the farmed landscape. Well-targeted agri-environmental incentives can enhance species abundance, but little is known about the scale of wildlife-friendly farming required to meet these targets nationally. In a new study, we addressed this question.

Agri-environment schemes

Agricultural intensification is a major driver of global biodiversity decline. In Europe, farmers are financially incentivised to create wildlife friendly habitats through agri-environment schemes (AES), the main mechanism for addressing these declines. Here in the UK these schemes underpin the conservation of our most sensitive species and habitats, from Corncrake in Western Scotland to Cirl Buntings in Devon and Cornwall.

Many AES focus on farmland birds which require a combination of seed-rich and insect-rich habitats for a year-round supply of food, plus adequate nesting habitat (Figure 1). AES can meet these requirements through a range of different options including sown wild bird seed mixes, sown flower-rich margins, and large fallow (bare ground) plots to provide in-field nesting opportunities (Figure 2). Farmers are encouraged to adopt multiple measures on the same holding.

From 2005 two tiers of AES were available in England under the Environmental Stewardship (ES) scheme. A ‘broad and shallow’ lower-tier (Entry Level Scheme, ELS), which encouraged farmers to adopt bird-friendly measures across 3-4% of their farm, and a more demanding ‘narrow and deep’ higher-tier (Higher Level Scheme, HLS), with a target minimum provision level of 7%. The higher-tier scheme was targeted at farms already holding priority farmland bird species and involved bespoke 1-2-1 landowner advice, and provides the backdrop to the current study.

Our approach

We set out to establish how much AES provision is required at the scale of individual farms and landscapes to enhance farmland bird abundance. To achieve this, we measured changes in the abundance of farmland birds across 67 farms deploying higher-tier AES over a ten-year period, with equivalent monitoring across lower-tier farms and farms with no bird-friendly AES.

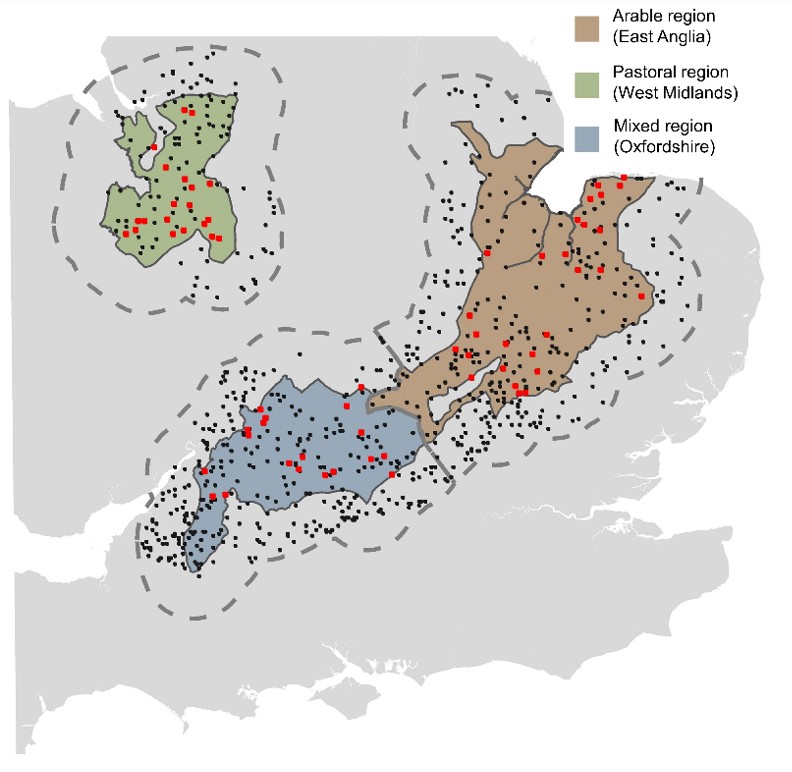

To help ensure that our understanding of AES performance was relevant to different farming systems, we monitored higher-tier, lower-tier, and no AES farms across three contrasting landscapes in lowland England (Figure 3). These were East Anglia (arable), Oxfordshire (mixed), and the West Midlands (pastoral).

How much bird-friendly AES is required at the farm-scale?

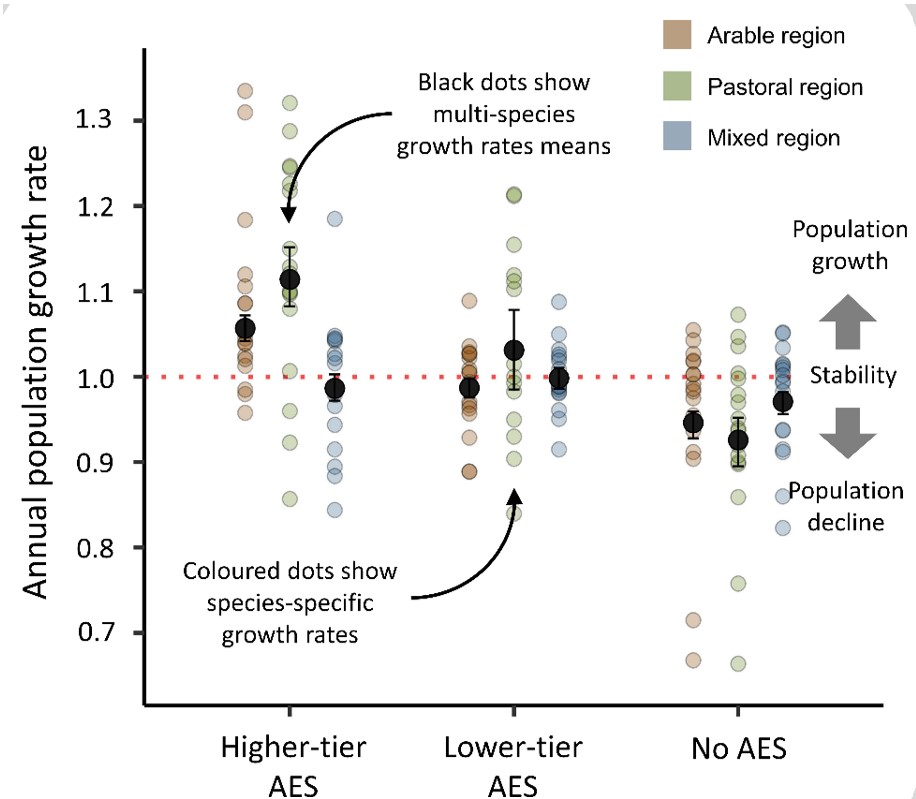

The key finding of this ten-year study is that higher-tier provision (i.e. on average 10% of the farmed area devoted to bird-friendly AES options) had a strong positive effect on the abundance of many farmland birds in two of the three regions, where in the absence of AES, numbers were declining (Figure 4). Specifically, in the arable and pastoral region, 13 out of 23/22 farmland bird species increased more strongly (or declined less severely) on farms with higher-tier AES compared to farms with no AES (the remaining 10 or 11 species showed no significant change).

The mixed region showed a different pattern, with 4 out of 22 species faring better on higher-tier farms compared to no AES farms. It is unclear why higher-tier AES did not yield a clear and consistent benefit in this one region, but we discuss the possible reasons in the article. By way of contrast, lower-tier provision only boosted the abundance of a few species. The average effect of lower tier AES provision across species was to stabilise abundance at the farm scale for species that would have continued to decline in the absence of any AES (Fig. 4).

How much bird-friendly AES is required at the landscape-scale?

So far we have demonstrated the value of higher-tier AES in two of the three regions, but how much of wider farmed landscape would need to be devoted to higher-tier agreements to recover farmland bird populations by 10% by 2030? Here we consider the group of 19 species comprising the Farmland Bird Index.

Through a set of simulations, described in the article, we predict that 47% of the farmed landscape in arable East Anglia and 26% in pastoral West Midlands would need to be devoted to higher-tier agreements to increase farmland bird populations (on average) if deployment is geographically untargeted and no lower-tier AES is available. In other words, 47% or 26% of farms would need to devote about 10% of their land to bird-friendly AES options. If Turtle Dove are excluded from East Anglia calculations (a specialist species with bespoke AES requirements), the estimate for this region is reduced from 47% to 31%. Turtle Dove were largely absent from the West Midlands and were not modelled here.

Our study also demonstrates a strong effect of geographic targeting. Specifically, if deployment is targeted to farms already supporting higher abundances of the target species, the higher-tier provision requirements are reduced from 31% to 21% (East Anglia), and from 26% to 17% (West Midlands). This higher-tier requirement reduced further if lower-tier AES is also present in the wider landscape.

The landscape-scale provision estimates reported so far consider a wide assemblage of farmland species, including widespread and relatively common generalists such as Jackdaw and Wood Pigeon. When our analysis focused only on species of conservation concern (‘priority bird’ species), or species restricted to farmland (‘specialist bird’ species), higher-tier provision requirements increased in both regions. For example, to increase specialist bird populations through geographically targeted deployment would require 33% (East Anglia) or 22% (West Midlands) higher-tier provision.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that AES can halt farmland bird declines across the wider farmed landscape, but sufficient deployment – both at the farm and landscape scale – are required. The amount of higher-tier AES required to achieve this varies between regions, but this is reduced with careful higher-tier targeting and additional lower-tier management.

If the UK is to meet its commitment of halting species declines in England by 2030, AES needs to be well resourced, targeted and appropriately administered to facilitate higher-tier uptake at the appropriate scales.

Acknowledgements

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and Natural England funded this work. We are grateful to the RSPB fieldworkers, the Environmental Stewardship agreement holders who allowed access to their farms for bird surveys and the British Trust for Ornithology and Breeding Bird Survey volunteers for data provision.