Walk into any grocery store to stock up for Halloween and you will discover that, for chocolate treats, you have two basic choices:

Will it be Mars or Hershey?

I often buy both, but that is beside the point. The point is that the two giants compete for market share, but both enjoy robust sales. In other words, a relatively stable duopoly defines the U.S. chocolate candy market.

But it wasn’t always like this.

Before the 1960s, the Hershey Chocolate Corp. reigned supreme as the undisputed chocolate king. It was in that decade that Mars went for Hershey’s jugular. Hershey Chocolate’s response brought lasting change – to its candy business, the local community and Hershey Park, its chocolate-themed amusement park.

As a professor of American studies at Penn State Harrisburg who has recently published a book on Hershey Park, I am astounded by how these changes continue to reverberate today.

Milton Hershey’s paternalistic capitalism

Before the 1960s, change was not a word one associated with either the town of Hershey, Pennsylvania, or its famous chocolate company. Better words would be “stability” and “productivity” – and this was by the founder’s design.

Bettman/Bettman Collection via Getty Images

When Milton Hershey entered the confection industry in the 1880s, violent clashes between corporations and labor roiled American society. Hershey imagined a better way: paternalistic capitalism.

In the early 1900s, he built a chocolate factory and planned community out in the farms and pastures of central Pennsylvania. Instead of offering men and women wage-earning jobs and nothing else, he took care of his workers. They owned nice homes and benefited from a generous array of free or subsidized services and amenities: snow removal, garbage collection, trolley lines, good schools, a junior college, zoo, museum, sports arena, library, community center and theater.

They even had their own amusement park.

But this was a reciprocal relationship. In return, employees were expected to work hard, exhibit loyalty, practice clean living and refrain from labor agitation. With the exception of a strike during the Great Depression, the company and town lived in harmony. Milton Hershey called the place an “industrial utopia,” and residents largely agreed.

“Moving to Hershey,” one recalled, “was like moving to paradise.”

Harmony also defined Hershey’s relations with Mars. At the time, Hershey produced only solid chocolate – think of Hershey bars and Kisses. In contrast, Frank Mars’ company specialized in chocolate-covered snacks, suches Snickers or Milky Way, in which milk chocolate is poured over nuts, caramel or nougat.

Where did that chocolate coating come from?

Hershey, of course.

In those days, Mars was a client, not a rival. Without competition, Hershey enjoyed the luxury of not having to worry about market share. Amazingly, the company did not advertise under Milton Hershey and continued this policy after his death in 1945.

Hershey in crisis

Everything changed in 1964. The catalyst for change was Forrest Mars, the founder’s hard-charging son who was a true disrupter.

After seizing control of his father’s company, Forrest Mars set his sights on dethroning Hershey. As reporter and author Joël Glenn Brenner explains, the younger Mars boldly terminated the partnership with Hershey while ordering his engineers to learn how to make Hershey-caliber chocolate in six months. He also modernized the factory and ordered a surge in advertising, all to wrestle market share away from Hershey, the “sleeping giant.”

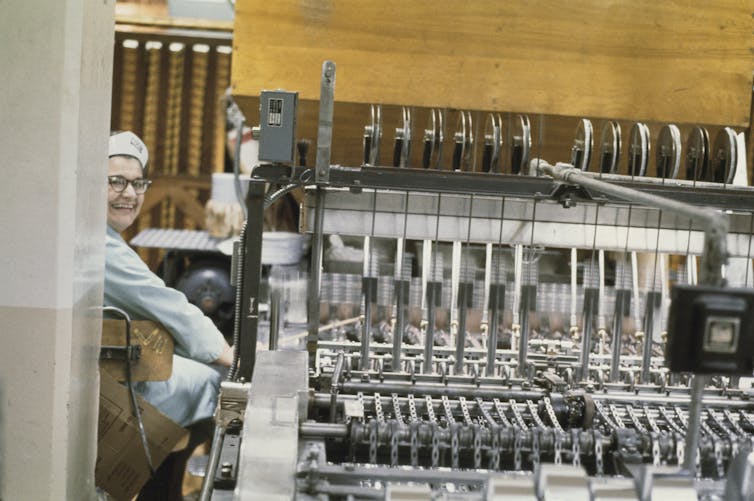

Peter Simins/Pix/Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images

The strategy worked. By the decade’s end, Mars had caught Hershey in terms of market share and pushed the chocolate colossus into crisis.

The good news for Hershey was that it had at the helm two forward-looking leaders, Harold Mohler and Bill Dearden. Though standard practice had always been to hire locally and from within, Mohler and Dearden recruited outsiders with MBAs from Harvard and Wharton to initiate sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing its archaic business practices.

The company opened a public relations office, conducted market research, installed IBM mainframe computers to crunch numbers, retrained its sales force and created a marketing department. Many employees, a new executive joked, were so behind the times that they had thought marketing was “what their wives did … with a shopping cart.”

This effort culminated with the release of the company’s first TV commercials starting in 1969. The sleeping giant had awoken.

The company’s next move altered the town forever. As a cost-cutting measure, it terminated the free services and amenities at the core of Milton Hershey’s vision. The era of paternalism was over.

As the company liquidated assets, residents howled in protest.

“It was a very traumatic time for the community,” one executive recalled.

For residents, the only consolation was that at least the amusement park would stay the same.

Or would it?

By the late 1960s, Hershey Park had degenerated into what one executive called “an iron park with a bunch of clanging rides.” Leadership faced a pivotal decision: renovate the park or close it forever.

The park had such a “rich heritage,” one executive recalled, that to shutter it would “put a stamp of negative feeling within the community.”

The company elected to renovate.

Hersheypark’s transformation

But how to renovate was another matter.

In the 1960s and 1970s, owners of traditional amusement parks had to think twice before investing in their properties. That was because Disneyland, the nation’s first theme park, had caused a sensation when it debuted in 1955. Its incredible popularity, and the opening of the more spectacular Disney World in 1971, placed pressure on old-fashioned amusement parks everywhere.

After commissioning a feasibility study, Hershey officials decided to gamble: Instead of fixing up the old amusement park, they would convert it into a Disney-style theme park. To pay for the massive overhaul, they redirected capital earned from the dismantling of Milton Hershey’s paternalism. Reborn as “Hersheypark” in 1973, the ever-growing complex has become a mecca for chocolate lovers and thrill-ride seekers from across the Northeast.

Lindsey Nicholson/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Every year, Halloween reminds me of this remarkable transformation. The stores become stocked with Hershey brands, and the theme park comes alive with its spooky “Dark Nights” entertainment.

In the past, workers at the Hershey plant would joke that they had “chocolate syrup in their veins.” These days, they clearly have innovation too, and that creative spirit is largely due to Forrest Mars. By giving Hershey the jolt it needed, he shook up the status quo and changed the chocolate company, town and park forever.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia and Pennsylvania.