German chancellor Olaf Scholz’s SPD has narrowly held off the rightwing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in regional elections in Brandenburg, nudging them into second place.

The close call follows two other recent elections in Germany’s eastern federal states (Länder). In Thuringia, the AfD won the highest share of the votes. In Saxony, the AfD narrowly came second to the centre-right CDU. Importantly, the regional AfD organisations in both Saxony and Thuringia, along with Saxony-Anhalt, have officially been designated as extreme right. This means that the party in these states is formally considered by Germany’s domestic security service to be a threat to the country’s democratic constitutional order.

Although the country’s proportional electoral system means that the AfD cannot form a government in any of the three states by itself, this is the first time since 1945 that an officially extremist party has won an election in Germany.

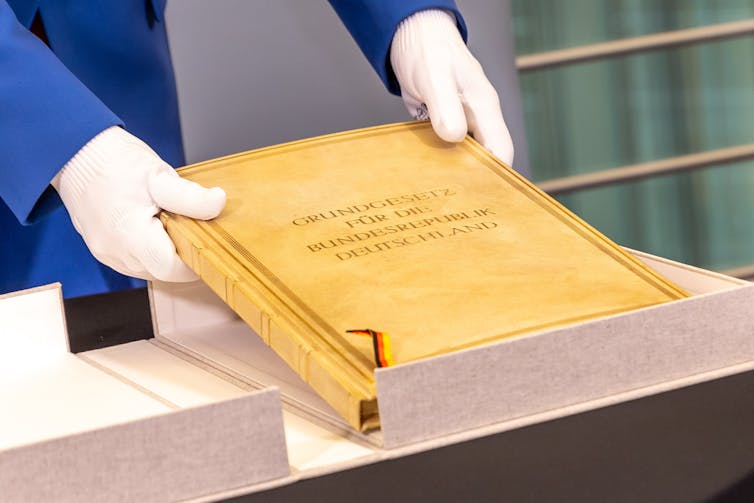

It’s not unreasonable for those outside Germany to questions whether these election results show that the country once more stands on the cusp of a slide into fascism, as it did in the 1930s. However, quite apart from the fact that 2024 is not the same as 1933, there is one important structural difference: Germany’s constitution (the Grundgesetz or Basic Law). This was explicitly designed to prevent a recurrence of a totalitarian regime such as national socialism.

The Basic Law dates back to 1949 – a time when the country was in the process of splitting into west and east. Coming into force during this period of transition, the document was only a provisional constitution. Yet the Basic Law has outlasted any of the previous three state forms since Germany was first unified in 1871. Today, it enjoys widespread popular support: a recent survey showed 81% of the population view it positively.

In its content, the Basic Law is a living testimony to Germany’s desire to prevent a return to National Socialism. In articles 1-19, it enshrines a comprehensive catalogue of fundamental rights, which cannot be removed from the constitution. These include the right to dignity, freedom, privacy, free assembly, freedom of the press and to political asylum.

The Basic Law also established one of the most powerful independent constitutional courts in the world. The court even has the right to ban political parties, or to limit the fundamental rights of individuals who are found to be undermining the constitutional order, as had been in the case in Weimar Germany. For this reason, Germany is considered to be a militant democracy. While the outright banning of parties is fraught with political difficulties (and hence rare historically), there is a live debate over whether the AfD’s policies and rhetoric are ultimately compatible with Germany’s constitution.

More subtly, Germany’s governance structures are designed to make it practically impossible for a hostile grouping to seize power democratically. The German chancellor has much less power than, say, the British prime minister. In particular, the structures of federalism and coalition government further constrain the room for manoeuvre of any individual politician or indeed any single political party.

Jakob-Kaiser-Haus/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Major functions of policy implementation are delegated to powerful societal actors, such as professional bodies. These are geographically distributed around the country, along with the media, key corporate headquarters and the unions. The ability of Germany’s central bank, the Bundesbank, to set monetary policy independent of political control, itself a response to the hyperinflation of the early 1920s, has made it a model for both the European Central Bank and the Bank of England today.

In short, and in the words of the German-American political scientist Peter Katzenstein, the German state is only “semisovereign”.

In consequence, the Basic Law is not just a document setting out the political “rules of the game”, but an expression of Germany’s values. Its longevity has benefited from the willingness of political elites down the years to adapt its provisions, where necessary, to changing circumstances. And in several respects, the past remains very much the present in German politics. For instance, the right to privacy, which was originally included to prevent the reoccurrence of Nazi Germany’s pervasive surveillance, is given new meaning in an age of global digital connectivity.

Pressures ahead

Certainly, Germany today faces multiple challenges. As society has evolved, Germany’s party system has fragmented, with more parties securing seats in the national parliament, the Bundestag. Of these, the AfD has been by far the most successful, and could potentially become the second largest party at the next parliamentary elections in 2025. This fragementation, which is not unique to Germany, has made the formation of coalition governments harder. Fortunately, this has so far not led to out-of-cycle national elections, of the kind which plagued the latter years of the Weimar Republic.

And there are concerns beyond politics. From the “economic miracle” in the 1950s, Germany’s growth has slowed significantly, averaging just 1.2% per year between 2012-2022; in the last two years, the economy has barely grown at all. Compared to other advanced economies, it remains disproportionately reliant on exporting high added value manufactured goods.

EPA/Andreas Gora

The reunification of Germany in 1990 also continues to cast a long shadow. In any number of economic and social indicators, including household incomes, religion and childcare patterns, eastern Germany remains structurally different to western Germany. Across the country, the population is ageing and, without substantial net migration over time, will decline over the next 30 years. Yet immigration also remains one of the biggest political issues of the day, and a key driver of the AfD’s electoral success.

Nonetheless, given Germany’s difficult journey to statehood in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Basic Law remains a strong guarantor of Germany’s democratic credentials. For this reason, former federal president Joachim Gauck was surely right to declare earlier this year that the Germany created by the Basic Law is “the best that ever existed”.