Forecasting earthquakes presents a serious challenge on land, but in the oceans that cover around 70% of the Earth’s surface it is all but impossible. However, the vast network of undersea cables that crisscross the world’s seas could soon change this. As well as transmitting data around the planet, they can also monitor the tectonic movements that cause earthquakes and tsunamis.

The “Fibre Optic Cable Use for Seafloor” project (FOCUS) has demonstrated how we can use existing fibre-optic cables to detect small movements on the seafloor caused by tectonic faults. Our aim is to improve understanding of fault activity, and therefore of possible earthquakes.

The project’s main study area was a recently mapped tectonic fault on the Mediterranean seafloor, about 30 km from Catania, Sicily. Sitting at the foot of Mount Etna, Europe’s highest and most active volcano, the fault is a “strike-slip”, a type of vertical fault in the earth’s crust that is especially prone to causing earthquakes.

The location is important. Eastern Sicily and Catania, an urban region of 1 million people, have been struck by several devastating earthquakes in recent centuries. The 1908 Messina earthquake (magnitude 7.2) and tsunami killed 72,000 people, while the 1693 Catania earthquake (estimated magnitude 7.5, the strongest in Italy’s history) killed about 60,000 people and destroyed most of the large buildings in Catania.

Catania is also home to a nuclear physics institute, the INFN-LNS, which runs an offshore research station consisting of a cabled seafloor observatory. Originally designed as a test site for for the institute’s neutrino telescope located 100km away, the southern branch of this 29km-long electro-optical cable ends just 2.5km from the recently mapped “strike-slip” fault on the seabed.

The FOCUS project worked by deploying a specially designed strain cable across the newly mapped fault in hopes of detecting tectonic movement. Any movement, however small, would tug on the cable and elongate the optical fibres inside. This can be detected by analysing laser light fired into the optical fibres.

Seabed cables

In October 2020, my team and I conducted our first marine expedition at the INFN-LNS site near Sicily, with the French Research vessel PourquoiPas?.

Author’s own, Author provided (no reuse)

First, we connected our specially designed 6km-long strain cable (similar to submarine telecommunication cables but with special sensor fibers) to the seafloor observatory. Using an underwater plough, this cable was then buried about 20 cm below the seafloor, crossing the fault in four different locations about 1km apart.

A set of 8 acoustic beacons was also set in place, 4 on each side of the fault. This was to independently measure any possible fault movement – any change in the baselines between the beacons would confirm there had been movement.

Laser light was then fired at regular 2 hour intervals through the research site’s 29km-long electro-optical cable and into the FOCUS strain cable, which included a triple loop in the fibres, allowing the light to go back and forth three times for a total optical path length of 47km.

The laser used a technique known as BOTDR (Brillouin Optical Time Domain Reflectometry). This has been used for decades to monitor deformation of large engineering infrastructures like bridges, dams and pipelines.

False alarms show the system works

A natural disturbance in the FOCUS fibre-optic cable was detected about 1 month later, in November 2020, representing an elongation of about 1.5 cm at the first fault crossing. At first it seemed the fault might have moved, but the acoustic beacons showed no change.

The most likely cause of the cable disturbance was a submarine landslide, akin to an avalanche of sediment at the bottom of the sea.

Author’s own

A second disturbance of the cable occurred in September 2021, but in this case we definitely know the cause. I led an operation that used an unmanned submarine to place weight bags on portions of the cable that were not well buried and lying on the seafloor, or spanning uneven terrain.

Nearly 100 weight bags (weighing 25kg each) were placed on top of the cable in 4 places, pushing the cable down into the soft mud and elongating the fibres inside. The special tight fibres in the FOCUS cable were more sensitive than the standard loose fibres used by the telecom industry, and showed very strong signals.

While these two readings did not show tectonic movement, they clearly demonstrated that undersea cables can help us closely monitor the seabed.

Commercial cables

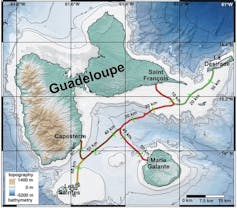

A secondary study area for the FOCUS project was a network of commercial telecommunication cables connecting the islands of the Guadeloupe archipelago. Over the three-year period between 2022 and 2024 I, along with partners at IDIL fibre optics, conducted a series of BOTDR measurements at 3-6 month intervals from roadside junction boxes.

We observed seasonal shifts in BOTDR signals in the shallow-water portions of the cable (typically at depths of 10-100m), likely from temperature variations on the seabed. To confirm this, we compared the temperature shifts based on our cable readings to independent satellite data. They were accurate to within about 0.1°C.

We also observed strong mechanical strain in the telecom cables at specific geographic locations such as shelf breaks, submarine canyons and narrow straits between islands exposed to storms and strong currents.

The results from our Guadeloupe study confirmed the accuracy and sensitivity of readings from commercial cables, as opposed to the more specialised cables used at the Catania site. They underscored their potential use for detecting mechanical disturbances to the cable (natural or man-made) and for performing long-term environmental monitoring.

Together, these results offer great promise for transforming much of the world’s vast network of submarine telecom cables into seismological and environmental sensors, to help better monitor earthquake hazard and climate change.

This article is the result of The Conversation’s collaboration with Horizon, the EU research and innovation magazine. In November 2025, the magazine published an interview with the author.