(New York) – The Beijing-controlled Legislative Council in Hong Kong passed a new security law on March 19, 2024, that eliminates the last vestiges of fundamental freedoms in the city, Human Rights Watch said today. The Safeguarding National Security Ordinance punishes peaceful speech and civil society activism with heavy prison sentences, expands police powers, and weakens due process rights. Because provisions apply to Hong Kong residents and businesses anywhere in the world, the law can silence dissent both in the city and globally.

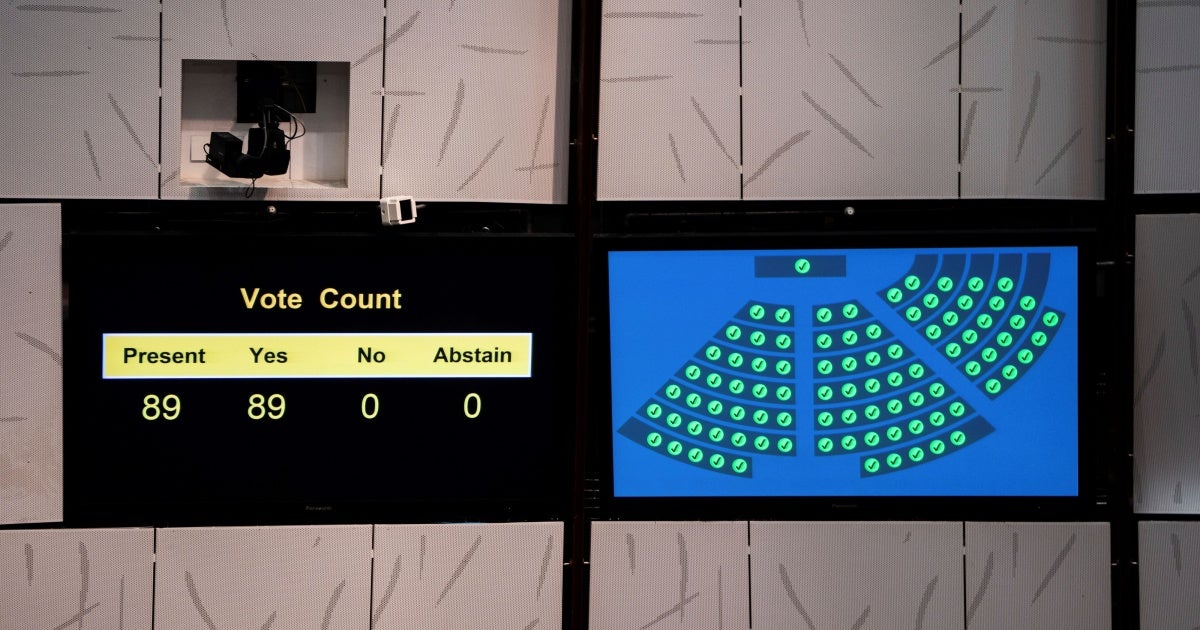

The legislature took only 11 days to pass the Ordinance unanimously. At the committee stage, the legislature reviewed the 212-page bill in 39 hours, with no amendments proposed. The law will come into effect on March 23.

“The new security law will usher Hong Kong into a new era of broad-based oppression,” said Elaine Pearson, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Now even possessing a book in Hong Kong critical of the Chinese government can mean years in prison.”

The Safeguarding National Security Ordinance covers treason; insurrection and seditious acts; theft of state secrets and espionage; sabotage; and external interference.

Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s de facto constitution since the United Kingdom transferred its sovereignty of the city to China, stipulates that the Hong Kong government should enact a law that safeguards national security. Hong Kong people have consistently opposed such legislation since at least 2003, when half a million people marched against it.

No genuine public consultation took place during the legislative process, Human Rights Watch said. After Beijing imposed the National Security Law on the city in June 2020, it dismantled the city’s pro-democracy movement by detaining and prosecuting elected representatives and thousands of peaceful protesters, eliminated civil society groups and independent labor unions, and shuttered its most popular pro-democracy newspaper, among other measures.

In February, the Hong Kong government conducted a four-week “public consultation” on Article 23 legislation and claimed that 98.6 percent of the submissions supported the proposal. It dismissed submissions and statements from international human rights groups and overseas Hong Kong activists and groups – over 100,000 Hong Kongers have fled the city – as “deliberate smears.”

The new law already has had a chilling effect on free expression. Local media reported that US- funded news outlet, Radio Free Asia, planned to withdraw from Hong Kong by the end of March.

The ordinance will further devastate human rights beyond those curtailed by the National Security Law. Its provisions contravene human rights guarantees enshrined in the Basic Law, and violate the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is incorporated into Hong Kong’s legal framework via the Basic Law and expressed in the Bill of Rights Ordinance.

The Australian, UK, and US governments, the European Union, and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights have all publicly expressed concerns about the law.

“The Hong Kong government should immediately repeal the Beijing-imposed national security laws, halt its aggressive assault on basic rights, and release all those arbitrarily detained,” Pearson said. “Foreign governments should hold Beijing accountable by imposing coordinated and targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on the Chinese and Hong Kong officials responsible, and protect overseas Hong Kong activists from Beijing’s long arm of intimidation and harassment.”

Broad and Vague Crimes

Definitions of many of the crimes in the Ordinance are overly broad, increasing the risks of politically motivated prosecutions and convictions.

The crime of “espionage” punishes those who, “with intent to endanger national security,” obtain, collect, or possess information that is “directly or indirectly useful to an external force” (clause 41).

The crime of “inciting disaffection of public officers” punishes those who “knowingly incite a public officer to abandon upholding the Basic Law,” or who simply possess documents “of such nature” (clauses 19-21).

The Ordinance defines “state secrets” as those concerning “major policy decision[s],” “economic or social development[s],” “technological development[s] or scientific technology,” and “diplomatic or foreign affair[s]” (clause 28). The chief executive, Beijing’s handpicked leader in Hong Kong, is authorized to decide what constitutes state secrets.

The Ordinance also broadly criminalizes acts with “seditious intention,” including an intention to bring anyone in Hong Kong “into hatred, contempt or disaffection” against the Chinese or Hong Kong governments, institutions, or constitutional order; an intention to “cause hatred or enmity amongst different classes of residents” in Hong Kong and China; and an intention to incite others to disobey the law or government order (clause 22). The threshold for conviction is low, as it is not necessary for the prosecution to prove an intention to incite public disorder or violence (clause 24). Additionally, the law empowers authorities to raid private premises to remove “seditious” publications and to “remove by reasonable force” anyone who obstructs the removal (clause 26).

Criminalization of Peaceful Association, Assembly and Activism

The Ordinance makes the freedoms of association, assembly, and peaceful civil society activism criminal offenses. It allows the government to ban organizations found to be engaging in activities broadly deemed to be endangering national security (clause 58). It also criminalizes “sabotage,” broadly defined as acts that “damage or weaken” public infrastructure, including public transportation systems, computer systems, and offices. Simply “being reckless” about national security can result in a 20-year prison sentence.

Some of the common tactics during the 2014 and 2019 protests, such as occupying major roads, would be subject to heavy penalties even if they were entirely peaceful.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment on the right to peaceful assembly, stated that “[w]here criminal or administrative sanctions are imposed on organizers of or participants in a peaceful assembly for their unlawful conduct, such sanctions must be proportionate, nondiscriminatory in nature and must not be based on ambiguous or overbroadly defined offenses, or suppress conduct protected under” international law.

The Ordinance also criminalizes “external interference,” defined as using “improper means” to collaborate with “an external force” to “bring about an interference effect” (clause 50). External forces include authorities of an external territory, external political organizations, and even international organizations (clause 6).

Interference includes influencing the Chinese and Hong Kong authorities and courts on the “formulation or execution” of any policy decisions (clause 51). Peaceful activities, such as criticizing the Chinese or Hong Kong governments’ human rights records at the United Nations or urging foreign governments to call on the Chinese and Hong Kong governments to comply with their international legal obligations to protect human rights, will violate the Ordinance. The maximum penalty for external interference is 14 years in prison.

Global Application

Hong Kong residents and Hong Kong incorporated bodies or businesses can violate the Ordinance anywhere in the world. The government can cancel their passports and suspend their qualifications to practice a profession (clauses 90, 93). Anyone who “directly or indirectly” funds the absconders may be sentenced to up to seven years in prison (clause 87).

Harsh Sentences for Peaceful or Protected Activities

The Ordinance spells out harsh sentences for peaceful activities. Anyone who “manages or assists in the management” of a banned organization could be given a maximum fine of HKD 1 million (US$130,000) and up to a 14-year prison sentence. Anyone who “is a member or claims to be a member of,” or “conducts any activity in cooperation with,” or simply “participates in a meeting” with or “pays money or give aid” to a prohibited organization may be fined a maximum HKD 250,000 (US$32,000) and sentenced to up to 10 years in prison. Even allowing meetings on one’s premises could lead to a HKD 250,000 fine and up to 7 years in prison (clauses 60-61).

“Unlawful” acquisition, disclosure and possession of the vaguely defined “state secrets” when leaving Hong Kong carry up to 5 to 10 years in prison.

The law raises the maximum sentence for “sedition” from the current 2 years to 7 years, despite repeated calls from the UN Human Rights Committee to repeal the archaic colonial-era law and refrain from using it.

Pretrial Detention; Access to Counsel

Under the Ordinance, the police may extend detention of a person arrested without charge from the current 48 hours to a further 14 days subject to court approval (clause 75). Police may restrict the right of a person under investigation or detention to consult with certain lawyers (clauses 76-77).

The ICCPR states that anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge must be “promptly” charged before a court. The UN Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that provides authoritative analysis of the covenant, has said that 48 hours is ordinarily sufficient time to bring someone before a judge, and that any longer delay “must remain absolutely exceptional and be justified under the circumstances.”

National Security Prisoners’ Treatment

Currently, Hong Kong prisoners are entitled to apply for a review of their sentence and may receive up to one-third reduction for good behavior. However, amendments to existing laws now prevent prisoners convicted under a national security offense from such reviews (clause 168), including prisoners with sentences imposed before the Ordinance was passed. Hong Kong has 1,829 such prisoners, according to the US-based Hong Kong Democracy Council.