Johanna Kauffert and co-authors take us back to one early morning of a fawn rescue in June in order to demonstrate how opportunistically sampled field data of wildlife volunteers can be used to reconstruct birth distributions.

It’s early morning (or rather still in the middle of the night) when I get up to drive to the countryside with my colleagues. Before the first rays of sunlight brighten the day, we meet up with a group of wildlife volunteers – they have big ambitions this morning. The farmers plan to mow 35ha grassland around the village today. Who knows how many animals are currently hiding in these meadows?

In fact, many field-dwelling animals such as ground-nesting bird species, leverets of brown hare or roe deer fawns use high-standing meadows as bedding sites and are prone to fall victim to mowing machinery. Particularly for roe deer fawns, spring mowing is one of the main mortality causes (ca. 15-30 %) due to their native instinct to stay hidden and motionless in jeopardy.

Thus every spring, many wildlife volunteers group up to search the meadows for fawns before mowing.

However, due to the limited days of mowing in spring which are restricted by favourable weather conditions, not all fields can be searched simultaneously. For now, exact knowledge of how much roe deer adapt to an earlier onset of spring introduced by climate change is still lacking.

Hence, on this particular June day, we do not even know how many fawns are still young enough to hide in the meadows.

We are arriving at the first meadow.

It is still quite chilly and the dew moistens the grass – perfect conditions to search for fawns with an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) as the thermal difference between the animal and the meadow is at its maximum.

The wildlife volunteers are setting up the UAV and start the ascent. Quickly, they detect a fawn and direct us to go into the meadow and search for it. We approach the fawn and hold on to it with gloves and a tuft of grass. We lift the fawn into a box and leave it at the side of the field. It will now wait until the meadow is mown and will be released afterwards.

In the meantime, one of the wildlife volunteers pulls out her phone, takes a picture of the fawn and enters the fawn’s age specifics and coordinates to our online form. Easy!

We continue our search for a couple more hours and at the end of the morning we were able to save eight fawns. At the same time, the wildlife volunteers generated valuable data for our study concerning bed sites and breeding phenology. What a success!

Reconstructing the breeding distribution

At the end of the fieldwork season, back at our computers at the university, we started analysing the data.

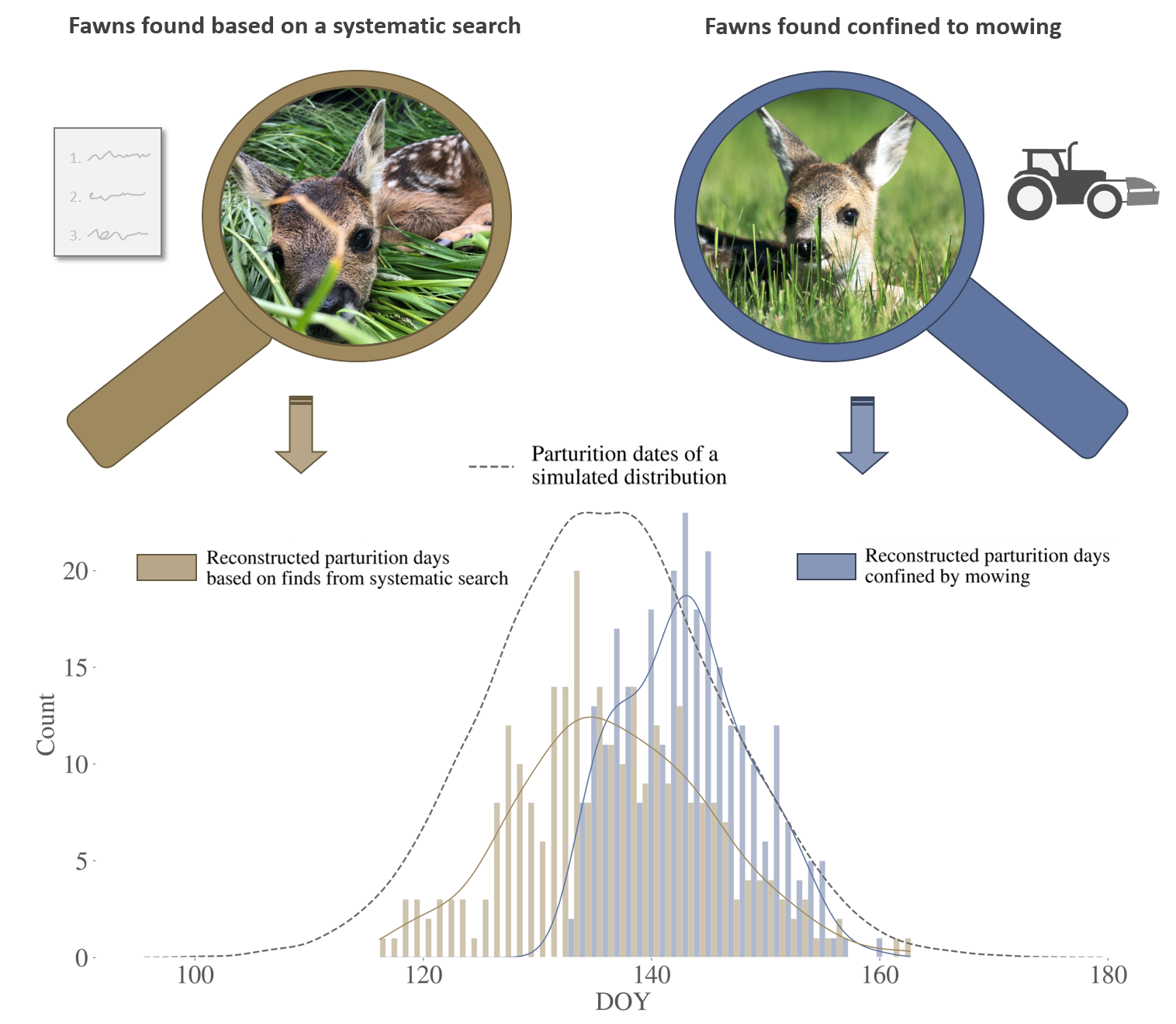

The search days of the volunteers look skewed as if they were only sampling at the end of spring. And yes, they were, because that’s when the weather was good for mowing. As a result, the reconstructed birth dates of the fawns also inherit the bias of this opportunistic search.

Luckily our independent research teams sampled data during the whole span of spring which is why we were able to model the truncation introduced by this opportunistically sampled data of the volunteers.

With a simulation exercise, we were able to describe the error of data sampled under different mowing regimes and developed two algorithms to address the drawbacks.

Our results were able to show that voluntarily collected data from roe deer fawn rescue initiatives can form an integral part to increase data size on regional birth distributions. This can potentially help to understand how much roe deer are adapting to environmental drivers such as climate warming. Moreover, better knowledge about the birth distribution can lead to more efficient searches during the mowing season and ease the threat of mowing deaths among roe deer fawns.

Finally, we invite fawn rescuers to actively engage in our research by reporting rescued fawns through our online form (QR code). This collaborative effort helps to expand our knowledge in breeding phenology but also with respect to related topics, such as preferred bedding habitats:

Read the full article: “Fawn birthdays: From opportunistically sampled fawn rescue data to true wildlife demographic parameters” in Issue 4:2 of Ecological Solutions and Evidence.