In recent months, the viability of France’s nuclear arsenal has been making headlines with talk of a French “nuclear umbrella” that might shield its allies on the European continent. In the face of the Russia-Ukraine war, and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s statements regarding the possibility of deploying nuclear weapons in that conflict, the question of how to best defend Europe has taken on an urgency not seen since the height of the Cold War.

Despite its more robust nuclear weapons capabilities, the United States in the Donald Trump era appears less committed to the defence of its NATO allies. Debates about a French nuclear umbrella aside, these discussions — combined with increased military spending worldwide and resurgent fears of nuclear war — make the history of France’s nuclear readiness and weapons testing feel uneasily current.

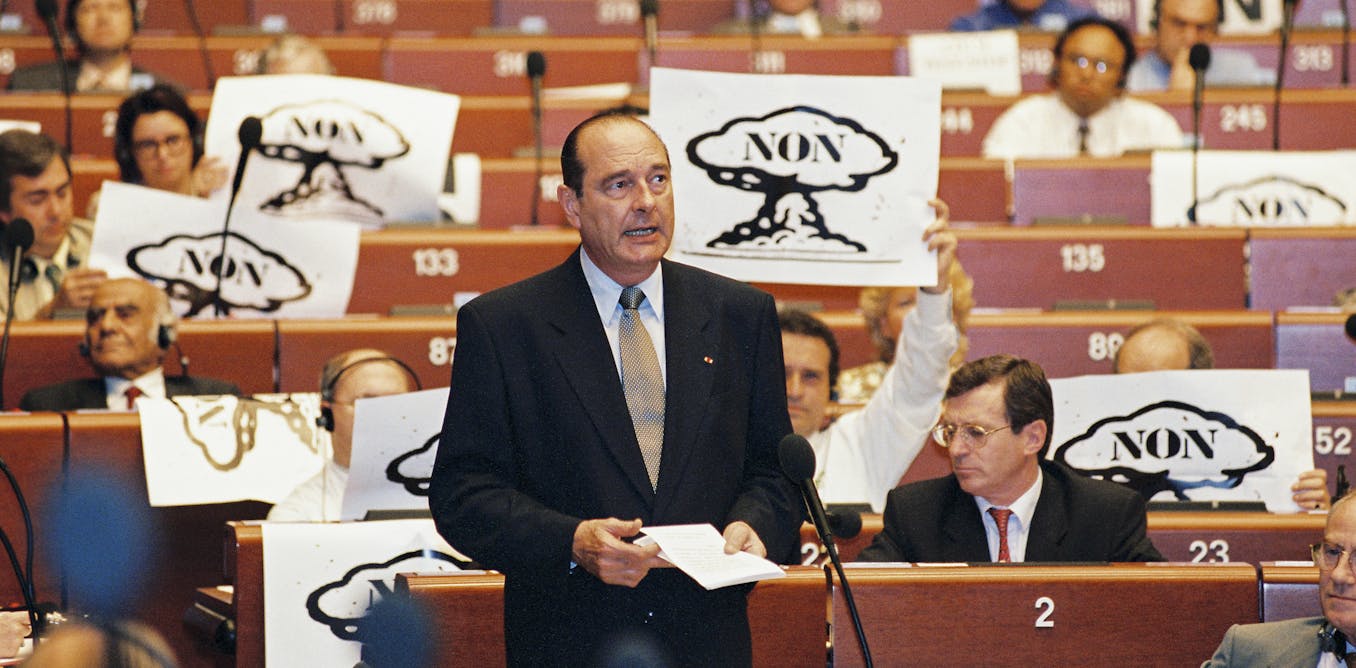

On June 13, 1995, French President Jacques Chirac announced that France would resume testing nuclear weapons in the South Pacific. Just weeks after being elected to office, Chirac ended a three-year moratorium on testing that his predecessor, François Mitterrand, had put into effect in April 1992.

Chirac insisted this additional series of weapons tests was essential to France’s national security and the continued independence of its nuclear deterrent. The eight planned detonations scheduled to take place over the next several months would, he claimed, provide the data needed to move from real-world detonations to computer simulations in the future. He also said it would enable France to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban-Treaty (CTBT) banning all nuclear explosions, for military or other purposes, by the fall of 1996.

France’s history of nuclear tests

Chirac’s June 1995 announcement, followed by the first new detonation in September that year, provoked intense opposition from environmental and peace groups, and protests from Paris to Papeete, throughout the Pacific region and across the globe.

Representatives from the world’s other nuclear-armed states expressed concern that France was choosing to conduct further tests so close to a comprehensive ban. The governments of Australia, New Zealand and Japan also registered their staunch opposition, issuing diplomatic statements, calling for the boycott of French goods and pursuing other measures of rebuke.

A defensive posture had been a pillar of France’s nuclear weapons policy since the nation first entered the atomic club in 1960 with the detonation of Gerboise Bleue, a 70-kiloton bomb, at Reggane in Algeria. The following three atmospheric and 13 underground Saharan tests resulted in serious long-term health and environmental consequences for the region’s inhabitants.

In 1966, France’s nuclear testing program relocated to Maō’hui Nui, colonially known as “French Polynesia.”

The next 26 years saw a further 187 French nuclear and thermonuclear detonations above and beneath the Pacific atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa. They exposed the local population to dangerous levels of radiation, contaminating food and water supplies, and harming corals and other forms of ocean life.

These experiments — along with the final six underground detonations the French carried out in 1995 and 1996 — left a toxic legacy for generations to come.

Inadequate compensation for lingering harm

When Chirac shared his rationale for France’s latest nuclear test series with a room full of journalists gathered at the Elysée Palace in June 1995, he was adamant that these planned tests, and all of France’s nuclear detonations, had absolutely no ecological consequences.

Today, we know this claim was more than incorrect. It was a falsehood reliant on data and conclusions that grossly underestimated the harmful impact that France’s nuclear testing program had on the health of French soldiers and non-military personnel onsite, inhabitants in the surrounding areas and the environments where these explosions took place.

Most recently, during the 2024 Paris Olympics, there was an evident deep contradiction between “French Polynesia” as a tourist paradise and idyllic location for the Games’ surf competitions and a space of continuing injustice for test victims that highlights the history of France’s nuclear imperialism in the region.

(AP Photo/Anat Givon)

In 2010, the French government passed the Morin law ostensibly aimed at addressing the suffering of those significantly harmed by radiation during France’s nuclear weapons detonations from 1960 through 1996.

The number of people who have been successful in their applications for recognition and compensation remains inadequate, particularly in Algeria. Out of the 2,846 applications submitted by only a fraction of the thousands of estimated victims, just over 400 people in Maō’hui Nui and only one Algerian have received compensation since 2010.

In 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron acknowledged that France “owes a debt” to the people of Maō’hui Nui. He has since called for the opening up of key archives pertaining to this history, but there is much more work to be done on all fronts.

The findings of a recent French parliamentary commission on the effects of testing in the Pacific, scheduled to be released soon, may contribute to greater transparency and justice for victims in the future.

In Maō’hui Nui, demands for acknowledgement and restitution have been intertwined with the independence movement, while confronting the impact and legacies of the nuclear detonations in Algeria has been fraught with tensions between Algeria and France over the colonial past.

Future of the test ban treaty

In January 1996, France conducted its last nuclear test by detonating a 120-kiloton bomb underground in the South Pacific. In September, France added its signature to the CTBT, joining the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, China and 66 other states without nuclear weapons in their commitment not to engage in further nuclear explosions in any context.

Almost 30 years later, the CTBT has still not come into force. While most signatories have ratified the treaty, China, Egypt, Iran, Israel and the U.S. are among the nine that have not. Meanwhile, Russia withdrew its own ratification in 2023. Key non-signatories include India, North Korea and Pakistan — all nuclear-armed states that have conducted their own tests since 1996.

Given these crucial exceptions to a test ban, the prospects for something as ambitious as the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which not a single nuclear weapons state has signed to date, remain uncertain, to say the least.