This story is part of a series that explores how school board meetings across the country are fomenting conflicts and controversies that have led to violence and arrests. Are you interested in a virtual event on this topic? Let us know here.

When one police officer heard the radio call for backup at a high school campus outside Little Rock, Arkansas, he first thought there’d been a problem at a football game. The indecipherable chanting in the background sounded like roars from the bleachers. But it turned out that the rhythmic rallying call that November night last year was coming from the lobby outside a school board meeting.

The prior two meetings, in September and October, had been held in Conway High School’s huge auditorium, equipped with ample seating and plenty of parking for what had, as of late, been larger crowds. There also had been an unusual amount of conflict. The day after the September meeting, police showed up at the homes of two residents to investigate separate incidents allegedly related to that meeting. At the October meeting, shortly before the board’s vote on policies that would restrict the rights of transgender students, a local grandfather stepped up to the microphone and warned the board about the sins of the LGBTQ+ community. “They invent ways of doing evil,” the man said during the public comment period. “But let me remind you that those that do such things deserve death.”

Alex Barnett, a junior philosophy major at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway, learned about tensions at the meetings on Instagram, where a video of the anti-LQBTQ+ comment to the board had gone viral. Barnett was motivated to do something. He pulled together a group, including members of a nascent Young Democratic Socialists club, at another student’s apartment. They brainstormed ideas for voicing opposition to the school board’s decision to pass the policies on transgender students.

Barnett had learned that the board had moved its November meeting back to the much smaller administration building and had decided to skip the part of the agenda where attendees could share their views. Given that none of the college students would be able to speak directly to board members, Barnett made a suggestion: “Well, why don’t we just go into the school board meeting and shut everything down?”

When the late-arriving backup officers got to the building, they first encountered a cluster of community members protesting on the sidewalk, some of whom had joined high schoolers staging a Conway High walkout earlier that day. Inside, the officers found a group of young people sitting on the lobby floor, their arms linked and their voices loud. “Trans Lives Matter!” they chanted. The officers warned them to clear out of the lobby. But they remained planted on the floor.

“I’ll start with this one here,” one officer said, leaning over Barnett. “You are required to leave. If you do not leave you’re being arrested. Do you understand?”

Barnett did not budge.

“Take him into custody,” the officer said, pointing to two other officers. The trio pulled Barnett off the lobby floor, clamping handcuffs on his wrists.

Another of the student protesters then calmly allowed officers to cuff him, accepting the arrest as the consequence of his resistance. A third protester kept chanting as he, too, was arrested. “These policies are discriminatory!” he yelled as officers ushered him out of the lobby. “Let them use the fucking bathroom!”

After pausing for eight minutes during the loudest of the chanting, the school board meeting resumed without interruption.

ProPublica has identified 59 people arrested or charged over an 18-month period as a result of turmoil at school board meetings across the country. The majority of the individuals railed against the adoption of mask mandates, the teaching of “divisive concepts” concerning racial inequity and the availability of books with LGBTQ+ themes in school libraries. Many of the people arrested were attempting to make a statement, narrating their interactions with police for their social-media followers. In some cases, they resorted to threats and violence.

The arrests in Conway stand out for several reasons. The college students organized in support of the issues that most other people who were arrested around the country opposed. What’s more, no arrests were made following two allegedly violent incidents stemming from the September meeting.

But the Conway arrests also reflect the pervasive challenges school districts and police departments across the country face in trying to figure out how to handle hordes of aggrieved citizens — and what to do when the clashes lead to chaos. In the coming weeks, ProPublica will be publishing stories about how that unrest has played out in various communities and has upended once-staid school board meetings.

Credit:

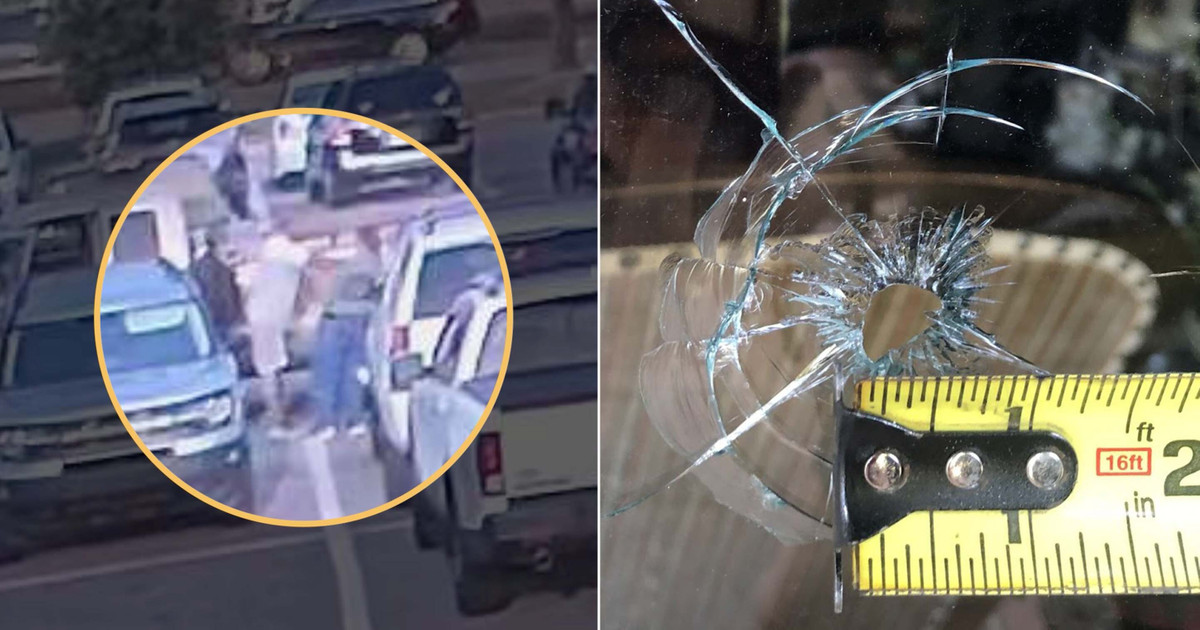

Courtesy of Cindy Nations

Cindy Nations was fast asleep when her alarm system warned of a “glass break” at 2:33 a.m. on Sept. 14. It wasn’t until later that morning, after she returned home from driving the early school bus route, that the recently retired teacher noticed the damage. Tiny slivers of glass glinted on the hardwood floors, on the armchair next to the fireplace and on the tray atop an ottoman. Then she parted her curtains and saw the hole.

Her mind immediately went to the school board meeting the night before. The meeting was the first after the start of the 2022-23 school year, and close to 200 people filed into the auditorium to hear the community’s input on two proposed policies concerning transgender students. One would bar them from using the bathroom that matches their self-identified gender. The other would require that, when traveling for school functions, they share hotel rooms only with a student who matches their gender assigned at birth. They’d also have the option to room alone.

One speaker also complained about what she called “sexually explicit” books available in school libraries across the state. She read passages to the board from three of those books: “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” “Wait, What?: A Comic Book Guide to Relationships, Bodies, and Growing Up” and “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out.” And she handed out a pamphlet with passages from those books to fellow concerned parents.

Nations and her friend Tamara Tucker were part of another cohort. Wearing a shirt printed with a rainbow to express her solidarity with LGBTQ+ attendees, Nations sat among like-minded parents and school employees near the back of the auditorium. They cheered on the mother of a transgender student who described to the school board the scrutiny her daughter faced after rooming with two girls during a school orchestra trip — even in the absence of a policy. “She had to report everything she’d done during the trip, and she was afraid she was in trouble,” the mother said. “These kinds of rules make no sense in the lives of actual children.”

The board itself didn’t act on the proposed policies at the meeting. That vote would come the following month.

Around 7:30 p.m., attendees made their way to the parking lot. Nations recalled that a group of people who’d congregated around a pickup truck stared her down as she walked toward her car. She would later tell police that “after leaving the school board meeting, she was followed home by a black SUV, but thought nothing of it.”

At about the same time, Tucker and her wife were standing in the parking lot, talking with other parents who were at the meeting to support LGBTQ+ students. Then, according to several of the parents, a truck almost hit Tucker’s wife.

A police officer arrived minutes later and asked what happened.

Tucker described how her wife said to the man: “Are you trying to run me over?” Then, Tucker said that “he kept yelling” — and that she yelled back: “Just move the fuck along.”

She said he climbed out of his truck, asking, “What did you say?” When she responded with, “I told you to move the fuck along,” she said the man pushed her. Parking lot surveillance obtained by ProPublica shows the man shoving Tucker.

“I flew back about three steps and hit the truck,” Tucker told the officer, Daniel Hogan, rubbing her shoulder and circling her arm. “It’s really hurting. It knocked the breath out of me.”

Credit:

Obtained by ProPublica

The following day, Hogan flipped on his body camera as he and his partner pulled up to the man’s brick ranch home. The officers were quick to assure him that he wasn’t being arrested. But the school was seeking a criminal trespass warning against him.

“What does that mean?” the man, Scott Simpson, asked.

“Basically, you can’t go back over to the school.”

“I can’t go to football games?” Simpson asked.

Simpson asked to tell his side of the story. He told the officers he’d gotten worked up during the school board meeting by the “pamphlets of the books.”

“I don’t know if you saw it, but it is boy-on-boy — it’s something I wouldn’t even look at,” Simpson told the officers. “And my temperature just, it elevated by looking at this stuff that’s in our public school system.”

He also described how, after the meeting, he drove his truck close to several women in the parking lot, complaining to the officers: “They just kept mouthing and cussing.”

“That’s when I pushed her,” he said. “I got in my truck and I left. That was all it was.”

Simpson then told Hogan, “You know, we go to church together.” Turning to the other officer, he pointed out that they’ve known each other for years, since Simpson’s sons were in junior high. “I am just not that type of person unless I am just provoked,” he said. “And it didn’t take much last night.”

“I understand,” Hogan said. “I definitely understand.”

“I’m glad you understand,” Simpson replied. “This world is going to shit. And I’m sure being a policeman you have to listen to both sides, but if you took your uniform off you would understand where I’m coming from.”

“Don’t have it off right now, though,” Hogan said, “so I’ve got to be indifferent on both sides.”

The night before, when Hogan took Tucker’s statement in the parking lot, he told her “he’d definitely pass that over to detectives” and that she could press charges if detectives didn’t. Eight months later, no charges have been filed. “I am undecided if I will pursue charges,” Tucker wrote in response to ProPublica’s questions, adding that she’d sought medical treatment later that week for bruises. Simpson did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

A Conway Police Department spokesperson said that because the investigation involved an allegation of third-degree battery, the department did not move forward with the case. “The Conway Police Department is following the rules of criminal procedure and cannot legally make an arrest on this specific offense as it did not take place in the presence of a police officer,” the spokesperson wrote, adding: “It will be the victim’s option to seek a misdemeanor warrant.” The spokesperson referred other questions about the incident to the city attorney, Charles Finkenbinder, who cited the same statute and said, “I am not aware of any request for charges in this matter.”

Nor did anything happen in Nations’ case. Though she told an officer she believed the damage to her window was from a gun, he found no bullet or bullet hole in her home, according to his police report. The report concluded that “the object may have been a BB or some other slower moving object like a small rock.” The day after the incident, the officer updated the report: “Due to lack of leads at this time, this incident will not be assigned for further investigation.” The Police Department did not comment on the Nations incident.

The only people who have faced charges for incidents stemming from the school board tensions in Conway last fall were the three college students who showed up at the school board meeting two months later.

In the two years leading up to her retirement, Nations had become distressed by what she saw in the junior high school where she taught — a reflection of larger debates raging in her district and nationwide.

“What happened in our country, how divided we became, just really spilled over into the classroom,” she said. “And it hurt me. It really hurt me.”

It started with a dust-up over “To Kill a Mockingbird.” The book had been taught in public schools for decades, but during the 2020-21 school year, Nations was stunned by a debate among administrators over whether it was appropriate for her ninth grade students. The concern was whether students should have to consider the role of race in the nation’s criminal justice system, a concept highlighted in the book. Nations, who’d taught English for 35 years, recalled her principal advising: “Right now with the current political climate, let’s not teach ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.’”

Conway Public Schools Superintendent Jeff Collum did not respond to questions about the events described in this story. In a statement last year to a local television station, a district spokesperson acknowledged that the book had been removed from the curriculum during the pandemic but said that it hadn’t been banned and that educators again had the option to teach it.

The debate over “To Kill a Mockingbird” reminded Nations of similar friction decades earlier. In the late ’90s, parents complained that Nations was teaching “The Chocolate War,” a controversial young adult novel that explores the mob mentality of a high school secret society and depicts bullying, violence and sex. Nations said that as a result of those concerns, the district created a committee to review the appropriateness of books being taught in classrooms. (That committee would be tasked in the fall of 2022 with considering the appropriateness of two books with LGBTQ+ themes, one of which the parent with the pamphlets had singled out; committee members recommended that the books remain on library shelves, but the board banned them anyway.)

In February 2022, things took another turn. Nations recalled that during her planning period, she was standing in her empty classroom with a colleague when another ninth grade English teacher walked in and plopped a poster down on a vacant desk. The teacher wanted to know what they thought of her Black History Month display for her classroom door.

Nations said her temperature rose when she saw what was on the poster: a photograph of a tree-lined lane leading to a grand Louisiana plantation.

The following week, according to Nations, another teacher posted her Black History Month poster in the hallway: “All Lives Matter,” it read.

“It divided my school family,” Nations said of the encroaching culture wars. “We were such a closely knit bunch, those ninth grade English teachers. We spent all our time together.” After February 2022, that was no longer the case.

At a tense faculty meeting that month, Nations lost her temper. The offensive displays. The book debates. Something felt very wrong. She recalled saying, “This has got to stop!” — and that the assistant principal told her to leave the meeting and go to her classroom. She said she refused.

“I could already tell they were going to just start telling me: ‘This is what you say and what you do. And you can’t veer from this in any way,’” she said. “And I just thought, that is not even teaching to me. That’s not what teaching is.”

The decision to retire came fast. But it wasn’t easy.

“I was so disappointed,” she said. “It had been just the best place to be, and then it became horrible.”

A week before finals last month, Barnett settled into a bench in the Conway courthouse, waiting for his name to be called. It was a Tuesday afternoon, more than five months after the protest.

His fellow protester Keylen Botley had been the first of the three students to be sentenced. At the urging of a church member, the 18-year-old had pleaded guilty months earlier to misdemeanor charges of criminal trespass and failure to disperse. He was fined $650.

Barnett had no plans of taking a plea deal. Instead, a judge would hear his case. At his bench trial, two of the arresting officers testified. Then Barnett took the stand.

“I wasn’t ashamed of what I did,” he said in an interview. “I felt like what I did was justified. I told the judge that, yeah, I’m the one who organized the protests. I’m not sorry for what I did at all. I would have gladly done it again.”

Of the 59 people ProPublica determined were arrested or charged for incidents stemming from school board unrest, Barnett received the stiffest sentence. The judge gave him 10 days in jail. ProPublica could not identify any others — including those who damaged school property or assaulted another attendee — who received a single day of jail time as punishment. The third student who’d been arrested in Conway, Colburn Clark, is scheduled for trial in late May.

Barnett said that during his day locked up, he was one of eight inmates in a windowless cell, with a shortage of first-come, first-serve beds. Barnett didn’t snag one; he got a yoga mat on the floor. Because the underwear he wore at the time he was booked was not white, and because he couldn’t yet buy any from the commissary, he went without. On the second day, his lawyer got him out on appeal.

Barnett said he’d hoped that the protest might have led the school board to reconsider the policies restricting transgender students. Instead, one of those policies was codified in state law when the newly elected governor, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, signed a bill in January denying transgender students access to the bathroom of their self-identified gender.

And this summer, another new law goes into effect, allowing anyone to challenge what they consider “obscene” books in public libraries. Local governments will decide whether to pull them from shelves. And library employees can be jailed and fined for “knowingly” distributing those books to minors. The offense would be a felony.

“I mean, it’s hard not to feel discouraged just by how fast that they’re going and how unstoppable this thing feels,” Barnett said. “But I think a lot of us are trying to resist that feeling of there’s nothing that we can do.”

Do You Have a Tip for ProPublica? Help Us Do Journalism.

Got a story we should hear? Are you down to be a background source on a story about your community, your schools or your workplace? Get in touch.

Mollie Simon contributed research.