Author Sarah Kingsbury shares a new integrated management approach to better assess the effects and risks of aquatic invasive species on Atlantic salmon in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Invasive species played key roles in the extinction of 60% of Earth’s plants and animals as reported by IPBES in 2023. While not all alien species introduced to new habitats become problematic (or even are able to establish long-term, reproducing populations), the species that do establish and cause negative impacts can affect ecosystems and indigenous species. They can have adverse impacts for people too, causing food insecurity, transmitting diseases and damaging infrastructure.

In Canada, our national identity is intrinsically tied to nature, especially for Indigenous Peoples, coastal communities, and rural communities, therefore limiting the impacts of invasive species on Canadian biodiversity is extremely important. However, it is not always clear how, where or which invasive species affect biodiversity.

Managing invasive species becomes even more difficult when trying to conserve vulnerable species with multiple threats or pressures, and we often do not have the full picture of where pressures are and what happens when you add all the pressures together. Also, the magnitude of each pressure is not consistent across the landscape. Some areas might have more or less logging activity, or more of an invasive species that affects the species of conservation concern .

So, how do we bring all these threads together to weave a plan for biodiversity conservation; and what species do we test the theory on?

Test Case: Atlantic salmon in Nova Scotia

Our idea was to develop an integrated management plan to inform aquatic invasive species (AIS) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) management in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Atlantic salmon is an iconic fish in Atlantic Canada and though historically all river systems in Nova Scotia are ‘suitable’ for Atlantic salmon, they have slowly been disappearing from certain areas. Why? There are many potential reasons and pressures but it’s difficult to allocate resources to effectively understand and address their impacts. Strategic deployment of limited resources requires managers to consider conservation needs in a holistic, integrated, ecosystem-based approach.

Integration

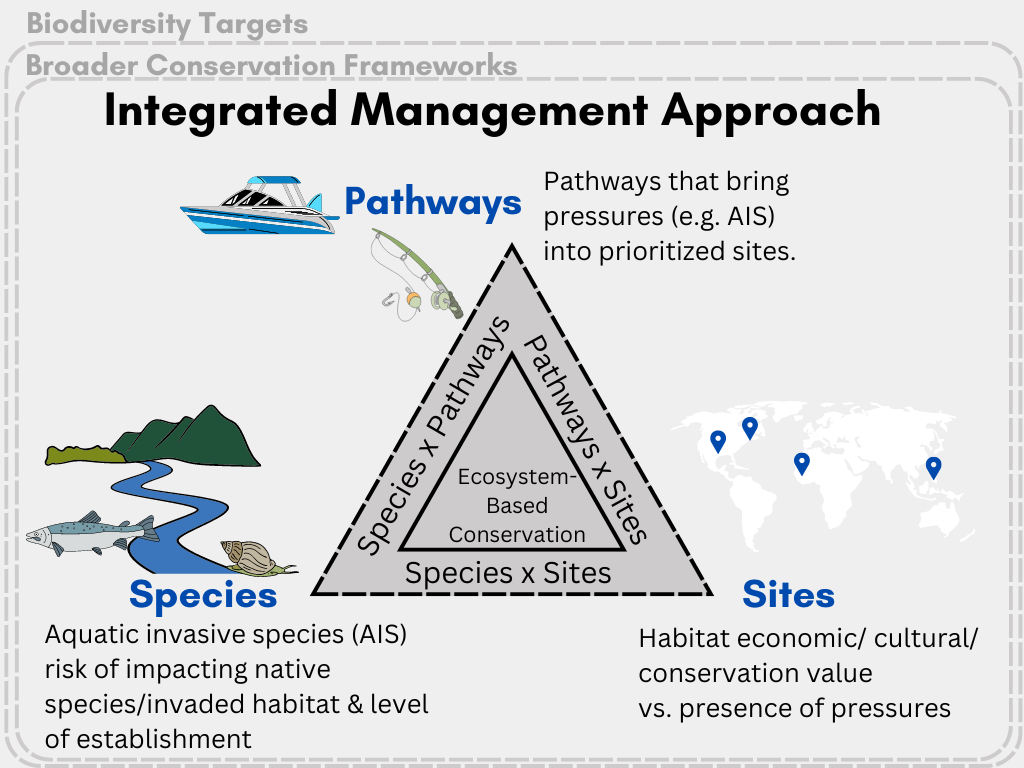

Our integrated management approach considers species, sites, and pathways, and their intersections. To put this in the context of our study, we first identified the number, types, and distribution of AIS before quantifying the risk of each AIS to affect Atlantic salmon. We then developed a management matrix that combined the degree of risk with their relative distribution (invasion stage in our study) to suggest what could be done to manage each AIS.

Next, we predicted all areas of the Eastern Appalachian drainage that were suitable for Atlantic salmon to look more closely at what pressures are more often associated with their presence or absence, and gain insight on what could be impacting populations.

To handle the changes in pressure magnitude over the landscape, we visualized the positive and negative habitat attributes (e.g. positive: parks, protected areas; negative: abundant AIS, predicted higher river warming) in flower plots, similar to what is used for Ocean Health Index, to compare the amount and type of pressures in each primary Nova Scotian watershed. This enabled us to identify sites with the most benefits to Atlantic salmon.

Lastly, we quantified the amount, type, and risk of vectors, such as recreational boating or fishing, that could lead to introduction of AIS.

Our findings

We found that Atlantic salmon was most impacted by pressures, including aquatic invasive species, that altered the physical habitat quality. In terms of AIS, we should prioritize preventing introductions of species that alter habitat structure and quality (i.e. ecosystem engineers) to high-value Atlantic salmon habitats. Hence, controlling the vectors associated with introducing ecosystem engineers should also be prioritized, especially in existing areas of better habitat quality.

In terms of conservation, there is always the argument of whether we deploy resources to the fish populations most at need (i.e. most depleted and threatened) or to the healthiest populations that might be more likely to survive. What we present in this study is a “where is the biggest bang for your buck” approach. Certainly more research is needed specific to each watershed, but this project provides some direction on where that research could start.

Read the full article: “A new tool for setting biodiversity management priorities adapted from aquatic invasive species management: a pilot using Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Nova Scotia, Canada” in Ecological Solutions and Evidence.