Baoshuang Hu and Wei Sun, Key Laboratory of Vegetation Ecology of the Ministry of Education, Jilin Songnen Grassland Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station, Northeast Normal University, discuss their article: Beyond species richness: grazing and fertilization shape temperate grassland stability through distinct stabilizing effects

Imagine a vast, windswept grassland. To the casual observer, it might look static, but beneath the waving green blades, a complex dance is happening. Plants are competing for sunlight, sharing nutrients, and responding to the weather. This dynamic interplay determines the ecosystem’s temporal stability—its ability to maintain productivity year after year despite environmental fluctuations.

For ecologists and land managers, this stability is the ‘holy grail’. We rely on grasslands for livestock forage, carbon storage, and biodiversity. However, human activities, particularly livestock grazing and nitrogen fertilisation, are rapidly changing these landscapes.

We know that biodiversity is generally good for stability. But here is the question that kept us up at night: Does human interference just change the level of stability, or does it fundamentally reshape how that stability is built?

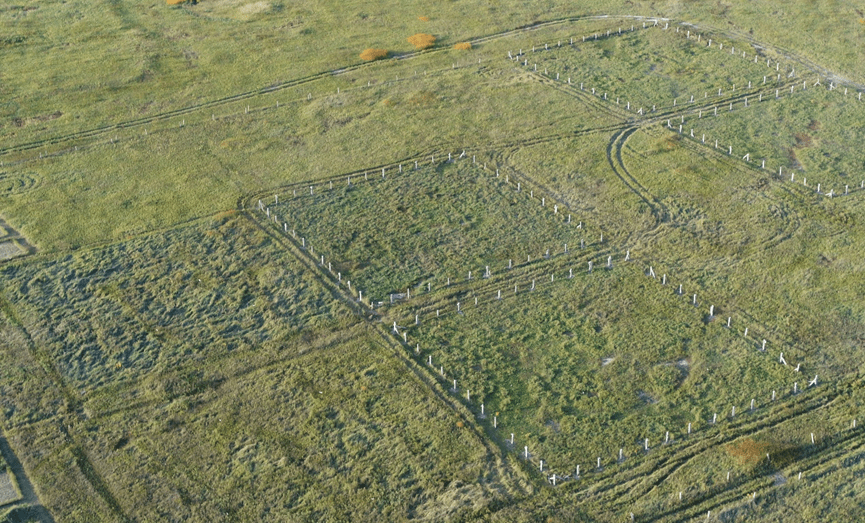

To find out, we spent nine years conducting a field experiment in the temperate meadow steppes of Northeast China. We set up plots simulating local traditional practices: moderate cattle grazing, nitrogen addition, and a combination of both. We wanted to look beyond simple species counts and peer into the “hidden architecture” of the ecosystem.

The two faces of stability

Our results showed that grazing and fertilisation pull the ecosystem in different directions. Even moderate grazing reduced stability by removing biomass—essentially weakening the system’s foundation. Fertilisation, on the other hand, helped buffer this effect by boosting growth. But the real surprise came when we looked at the mechanisms—the “how”. We discovered that land use decouples the pathways to stability.

Grazing creates “structural rigidity”: Under grazing pressure, the community became dominated by specific grazing-tolerant species, such as the rhizomatous grass Leymus chinensis. Stability here was maintained by the sheer persistence and resilience of these dominant plants. It is like building a stone arch; it is stable because its core components are robust and unchanging.

Fertilisation promotes “dynamic flexibility”: In contrast to grazing, fertilised plots maintained stability through asynchrony. When one species had a bad year, another had a good year, compensating for the loss. This is more like a suspension bridge; it stays stable by being flexible and allowing its many parts to move and adjust.

Introducing “interaction stability”

One of the most exciting parts of our study was the use of a new metric we call ‘interaction stability’. While counting species tells us who is there, we wanted to measure the persistence of the community’s overall ‘social structure’. Using nine years of field data, we tracked the ratio of competitive versus cooperative associations and calculated how consistently this balance was maintained over time. Instead of focusing on every single friendship or rivalry, we looked at the big picture: does the net balance between competition and cooperation remain steady year after year, or does the whole system constantly fluctuate?

We found a fascinating trade-off. Communities with high species richness tended to have lower interaction stability. This sounds counter-intuitive, but it makes perfect sense under our “architecture” theory. Rich communities are flexible; they survive by constantly rewiring their internal interactions. Poor communities are rigid; they survive because their simple interactions are set in stone.

Why does this matter?

Our findings reveal that there is no single “magic bullet” for ecosystem stability. Nature uses different architectural blueprints depending on the environmental context.

For land managers, this means we cannot just focus on preserving species numbers. We need to understand the functional pathways. In our study, we found that combining moderate nitrogen supplementation with grazing may effectively balance the trade-offs. It helped maintain productivity (thanks to fertilisation) while preserving the natural compensatory dynamics that kept the system resilient. Of course, every ecosystem is unique. While stability in our meadows relies on a specific dominant grass, other grasslands might depend on different ‘load-bearing’ elements. However, the broader lesson remains: land use doesn’t just damage grasslands; it redesigns them. By understanding these new blueprints, we can better protect these vital ecosystems in a changing world.