Chemistry deals with that most fundamental subject: matter. New drugs, materials and batteries all depend on our ability to make new molecules. But discovery of new substances is slow, expensive and fragile. Each molecule is treated as a bespoke craft project. If a synthesis works in one lab, it often fails in another.

The problem is that any single molecule could have an almost infinite number of routes to creation. These routes are published as static text, stripped of the context, timing and error correction that made them work in the first place. So while chemistry is often presented as one of the most advanced sciences, its day-to-day practice remains surprisingly manual.

For centuries prior to the emergence of modern chemistry, alchemists worked by hand, mixing substances, adjusting conditions by feel, passing knowledge from teacher to student while keeping many secrets. Today’s chemists use far more analytical tools, yet the core workflow has barely changed.

We still design molecules manually using the rules of chemistry, then ask highly trained humans to translate these ideas into reality in the laboratory, step by step, reaction by reaction.

At the same time, we are living through an explosion in artificial intelligence and robotics – and chemists have rushed to apply these tools to molecular discovery. AI systems can propose millions of candidate molecules, rate and optimise them, and even suggest reaction pathways.

But frustratingly, these tools frequently hallucinate chemicals that cannot be made, because (unlike in the case of proteins) no one has yet captured all the practical rules for making molecules digitally.

Chemistry cannot become truly digital unless it is programmable. In other words, we need to be able to write down, in a machine-readable way, how to assemble molecules – including instructions, conditionals, loops and error handling – and then execute these instructions on different hardware in different places with the same outcome.

Without a language that allows chemistry to be executed, not just described, today’s cutting-edge AI tools risk generating little more than plausible-looking illusions of new chemical substances. This is where using the computer as an architecture to build a digital chemistry system, or “chemputer”, becomes imperative in my view.

Before computers, calculation was manual and mechanical. People used slide rules, tables and specialist devices built for specific tasks. But when Alan Turing showed that any computable problem could be expressed as instructions for a simple abstract machine, computation was liberated from having to be done on specific hardware – and progress became exponential.

Chemistry has never made that jump. Akin to chefs using individual methods to achieve the perfect souffle, researchers around the world have different ways of preparing chemicals. So while automation in chemistry exists, research remains largely artisanal in nature.

An AI can design a thousand hypothetical drugs overnight. But if each one requires a human chemist to manually work out how to make it because the molecules generated are not constrained by the real-world rules of chemistry, we have simply moved the bottleneck. Design has gone digital, making has not.

Chemistry by computers

To properly digitise chemistry, we need a programmable language for matter to encode these real-world rules. This idea led me, with colleagues in my research laboratory at the University of Glasgow, to develop the process of chemputation back in 2012.

We built a concrete abstraction of what a chemical code would look like – with steps such as “add/subtract matter then add/subtract energy”. By translating these steps into binary code, it was possible to build the components of a chemputer.

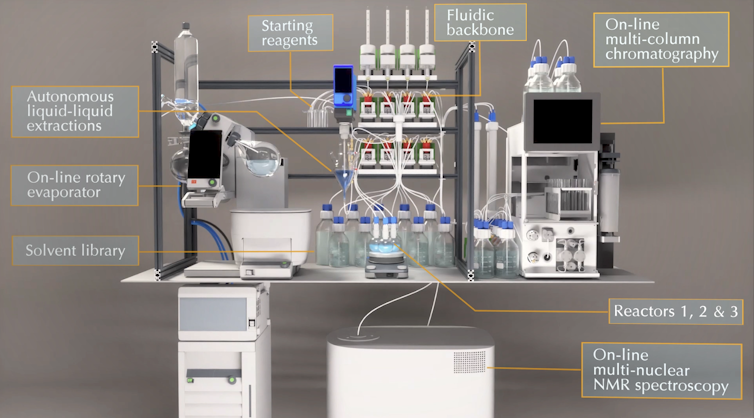

The premise is simple. Chemistry can be treated as a form of computation carried out in the physical world. Instead of publishing chemistry as prose, it is published in executable code, as described in our new preprinted article. Reagents are data. Operations like mixing, heating, separating and purifying are instructions. A range of machines, such as those shown in the image below, play the role of processors.

Lee Cronin, CC BY-NC-SA

Once chemistry becomes programmable, we expect many things to change. Reproducibility improves because processes are no longer interpreted by humans. Sharing becomes meaningful because a synthesis can be run, not re-imagined. Importantly, programmable chemistry allows feedback loops for error correction, with sensors monitoring reactions in real time.

Self-driving laboratories

Our ambitions for chemputation took a major step forward in June 2025 when Chemify, our University of Glasgow corporate spin-out, launched the world’s first chemifarm. At this facility in Glasgow’s Maryhill district, the process of chemputation is applied to making new molecules for drug and materials discovery.

It uses AI and robotics to enable the entire system to “self-learn”, and thus get better at making more advanced molecules over time. Discovery becomes an iterative, programmable process rather than a linear gamble.

This fits with the wider emergence of “self-driving” laboratories – robotic labs we pioneered that use AI and automation to enhance the speed and breadth of research.

Chemistry began as alchemy – a human art shaped by intuition and mystery, making potions, manipulating precious metals and building the first laboratory equipment. It has since grown into a rigorous science, yet never fully escaped its manual roots. If we want chemistry to keep pace with the digital age, especially in an era dominated by AI, we must now finish that transition.

![]()

Lee Cronin is the CEO and shareholder in Chemify and is the regius Professor at the University of Glasgow and recieves funding from many organisations including the UKRI Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.