Diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are rising rapidly in the UK. More children and teenagers than ever are being referred for assessment and support, and families are often facing long waits and limited options once a diagnosis is made. Schools, health services and parents are all under growing pressure to find treatments that genuinely help children manage their difficulties with attention, impulsivity and activity levels.

At the same time, there is no shortage of new ideas being promoted as solutions. Some are supported by evidence, while others sound promising but rest on much shakier foundations. One of the challenges for families is working out which treatments are truly effective and which are driven more by hope than by solid proof.

For many children with ADHD, stimulant medication such as methylphenidate is known to be highly effective. Decades of research show that these medicines can reduce core symptoms and help children function better at home and at school. For some families, medication can make a life-changing difference.

Even so, medication is not an easy choice for everyone. Many parents and young people worry about side-effects, stigma or the idea of taking medication long term. These concerns are understandable and often lead families to look for alternatives that feel more natural or less medical.

Against this backdrop, brain stimulation devices have increasingly been promoted as a drug-free option for ADHD. These devices deliver very mild electrical stimulation to specific nerves or parts of the brain. They are generally considered safe, with side-effects that tend to be mild and short-lived, such as skin irritation or tingling. Safety, however, is not the same as effectiveness.

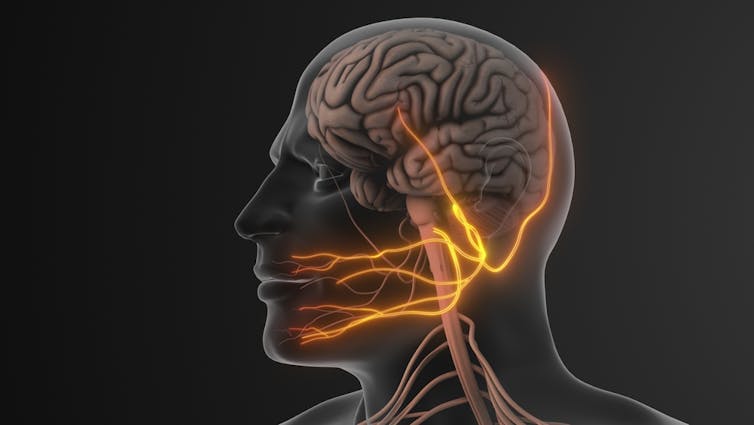

One of the most widely discussed of these technologies is trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS). The trigeminal nerve is the largest nerve in the face and carries signals to the brain. Devices using this approach are worn on the forehead and deliver gentle electrical pulses, usually during sleep. The idea is that stimulating this nerve might influence brain systems involved in attention and self-control.

JitendraJadhav/Shutterstock.com

This technology became the only medical device cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for ADHD in children in 2019. For many families seeking non-medication options, regulatory clearance can suggest effectiveness, even when the supporting evidence is limited.

What is less widely understood is that this decision was based on very limited evidence. The main study supporting clearance involved just 62 children. While the study reported improvements in ADHD symptoms, it had major weaknesses. In particular, the children who were meant to act as a comparison group received no stimulation at all.

This matters because expectations can strongly influence how people experience and report symptoms, especially when a treatment involves advanced technology. If children or parents can easily tell whether a device is switched on, beliefs about whether it “should” work can affect how improvements are noticed or reported, even if the device itself has no real effect.

Despite these limitations, FDA clearance helped legitimise the device and fuelled interest around the world. TNS began to be marketed in private clinics, including in the UK, often at significant cost to families.

Some families bought the device abroad or through private providers, hoping it would offer benefits without medication. Meanwhile, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has taken a more cautious stance, saying that stronger evidence is needed before such devices could be recommended within the NHS.

It was clear that better evidence was needed to answer a simple question that matters deeply to families: does TNS actually help children with ADHD?

Testing the claim

Our new study was designed to find out. We carried out a large, independent UK clinical trial of TNS, recruiting 150 children and teenagers with ADHD in London and Southampton. This made it substantially larger than the studies that had come before. Crucially, our study was designed so that expectations were carefully controlled.

Children in both groups wore identical-looking devices, and both groups felt sensations from the device. This meant that neither families nor participants could easily tell whether they were receiving real stimulation or a placebo version. This kind of design allowed us to test whether TNS itself had any effect beyond expectation alone.

Our findings were clear. We found no evidence that trigeminal nerve stimulation improved ADHD symptoms. Children who received active stimulation did no better than those who received the placebo device. There were no improvements in attention, behaviour, anxiety, mood or sleep.

These results challenge the earlier study that led to regulatory clearance in the US. They also highlight why large, carefully designed trials are so important, particularly for treatments that generate excitement and hope. Without strong controls, it is easy to mistake expectation for effectiveness.

Technology-based brain treatments are especially vulnerable to this problem. When families are told that a device can “correct” or “normalise” brain activity linked to ADHD, expectations can understandably run high. Without rigorous testing, this can lead to the benefits being overstated and families being misled.

For families in the UK, the message from our research is an important one. TNS appears to be safe, but safety alone is not enough. A treatment that does not work offers no real benefit and may divert time, money and energy away from approaches that are known to help.

Our findings also serve as a reminder that official approval or marketing claims do not always mean a treatment is effective. Clearance can sometimes reflect that a device is safe to sell, not that it has been proven to work well.

ADHD can be a serious and lifelong condition for many children and young people. As diagnoses continue to rise, so too does the responsibility to ensure that families are offered support and treatments guided by robust evidence – not hype, hope or premature conclusions.

The Conversation asked NeuroSigma, the maker of the TNS device mentioned in this article, to comment on the issues raised in this article. A company spokesperson said the study design mentioned in this article may have limited the ability to detect treatment effects. In particular, they noted that the primary outcome measure relied on parent-reported assessments rather than clinician-rated ADHD scales. NeuroSigma maintains that clinician assessments are more reliable and less prone to bias, and says it is therefore unsurprised by the study’s findings.

NeuroSigma also highlighted an ongoing, larger double-blind randomised controlled trial led by researchers at UCLA, involving 225 children and using clinician-rated outcomes alongside biomarker data. The company says it expects results from this study later this year and believes they will confirm both the safety and effectiveness of eTNS therapy.

![]()

This project was funded by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Programme (NIHR130077), a Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) partnership. The design, management, analysis and reporting of the study are independent of the funder and the device manufacturer. Katya Rubia is also supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS foundation Trust and King’s College London (NIHR BRC Maudsley) and by NIHR grant (NIHR203684), Medical Research Council (MRC) (APP32868), Medical Research Foundation (MRF-176-0002-RG-FLOH-C0929) and Rosetrees Foundation (3442198). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the MRC, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care or any of the other funding bodies.

Aldo Alberto Conti does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.