In the aftermath of the U.S. military strike that seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3, 2026, the Trump administration has emphasized its desire for unfettered access to Venezuela’s oil more than conventional foreign policy objectives, such as combating drug trafficking or bolstering democracy and regional stability.

During his first news conference after the operation, President Donald Trump claimed oil companies would play an important role and that the oil revenue would help fund any further intervention in Venezuela.

Soon after, “Fox & Friends” hosts asked Trump about this prediction.

“We have the greatest oil companies in the world,” Trump replied, “the biggest, the greatest, and we’re gonna be very much involved in it.”

As a historian of U.S.-Latin American relations, I’m not surprised that oil or any other commodity is playing a role in U.S. policy toward the region. What has taken me aback, though, is the Trump administration’s openness about how much oil is driving its policies toward Venezuela.

As I’ve detailed in my 2026 book, “Caribbean Blood Pacts: Guatemala and the Cold War Struggle for Freedom,” U.S. military intervention in Latin America has largely been covert. And when the U.S. orchestrated the coup that ousted Guatemala’s democratically elected president in 1954, the U.S. covered up the role that economic considerations played in that operation.

A powerful ‘octopus’

By the early 1950s, Guatemala had become a top source for the bananas Americans consumed, as it remains today.

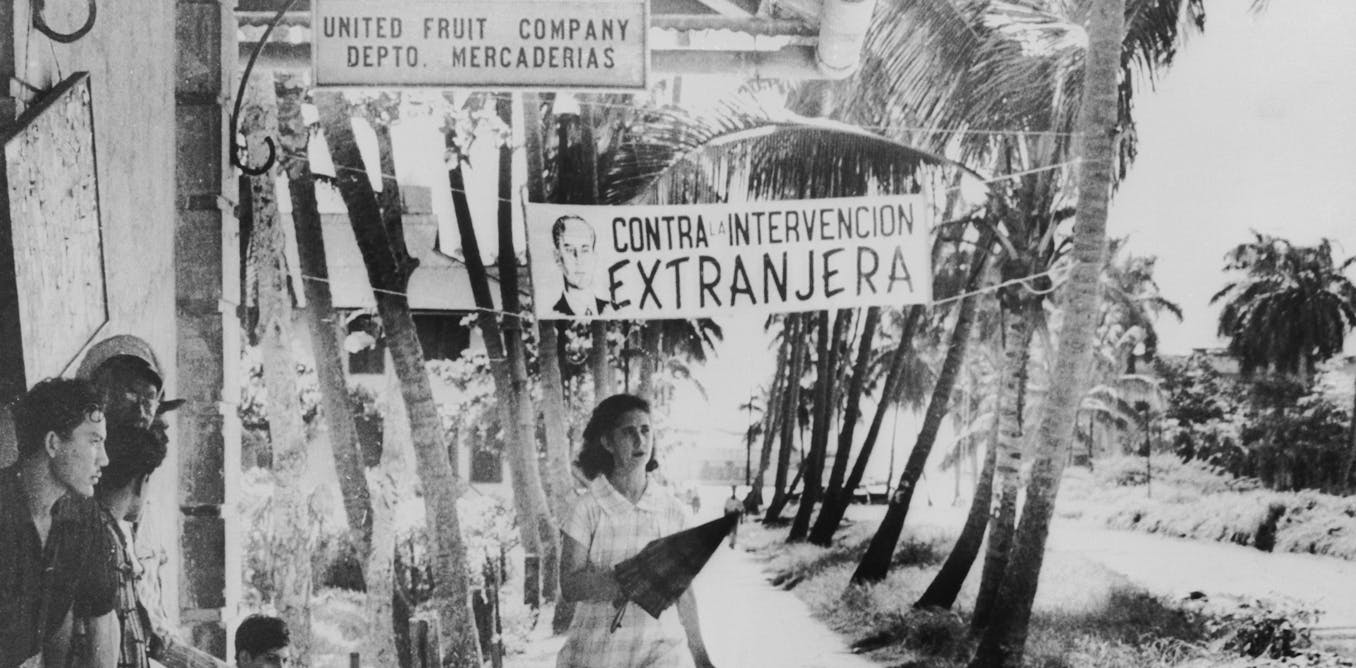

The United Fruit Company owned over 550,000 acres of Guatemalan land, largely thanks to its deals with previous dictatorships. These holdings required the intense labor of impoverished farmworkers who were often forced from their traditional lands. Their pay was rarely stable, and they faced periodic layoffs and wage cuts.

Based in Boston, the international corporation networked with dictators and local officials in Central America, many Caribbean islands and parts of South America to acquire immense estates for railroads and banana plantations.

The locals called it the “pulpo” – octopus in Spanish – because the company seemingly had a hand in shaping the region’s politics, economies and everyday life. The Colombian government brutally crushed a 1928 strike by United Fruit workers, killing hundreds of people.

That bloody chapter in Colombian history provided a factual basis for a subplot in “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” an epic novel by Gabriel García Márquez, who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1982.

The company’s seemingly unlimited clout in the countries where it operated gave rise to the stereotype of Central American nations as “banana republics.”

Guatemala’s democratic revolution

In Guatemala, a country historically marked by extreme inequality, a broad coalition formed in 1944 to overthrow its repressive dictatorship in a popular uprising. Inspired by the anti-fascist ideals of World War II, the coalition sought to make the nation more democratic and its economy more fair.

After decades of repression, the nation’s new leaders offered many Guatemalans their first taste of democracy. Under Juan José Arévalo, who was democratically elected and held office from 1945-1951, the government established new government benefits and a labor code that made it legal to form and join unions and established eight-hour workdays.

He was succeeded in 1951 by Jacobo Árbenz, another democratically elected president.

Under Árbenz, Guatemala implemented a land reform program in 1952 that gave landless farmworkers their own undeveloped plots. Guatemala’s government asserted that these policies would build a more equitable society for Guatemala’s impoverished, Indigenous majority.

United Fruit denounced Guatemala’s reforms as the result of a global conspiracy. It alleged that most of Guatemala’s unions were controlled by Mexican and Soviet communists and painted the land reform as a ploy to destroy capitalism.

Lobbying Congress to intervene

In Guatemala, United Fruit sought to enlist the U.S. government in its fight against the elected government’s policies. While its executives did complain that Guatemala’s reforms hurt its financial investments and labor costs, they also cast any interference in its operations as part of a broader communist plot.

It did this through an advertising campaign in the U.S. and by taking advantage of the anti-communist paranoia that prevailed at the time.

United Fruit executives began to meet with officials in the Truman administration as early as 1945. Despite the support of sympathetic ambassadors, the U.S. government apparently wouldn’t intervene directly in Guatemala’s affairs.

The company turned to Congress.

It hired the lobbyists Thomas Corcoran and Robert La Follette Jr., a former senator, for their political connections.

Right away, Corcoran and La Follette lobbied Republicans and Democrats in both chambers against Guatemala’s policies – not as threats to United Fruit’s business interests but as part of a communist plot to destroy capitalism and the United States.

The banana company’s efforts bore fruit in February 1949, when multiple members of Congress denounced Guatemala’s labor reforms as communist.

Sen. Claude Pepper called the labor code “obviously intentionally discriminatory against this American company” and “a machine gun aimed at the head of this American company.”

Two days later, Rep. John McCormack echoed that statement, using the exact same words to denounce the reforms.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Sen. Lister Hill and Rep. Mike Mansfield also went on the record, reciting the talking points outlined in United Fruit memos.

No lawmaker said a word about bananas.

Lobbying and propaganda campaigns

This lobbying and communist talk culminated five years later, when the U.S. government engineered a coup that ousted Árbenz in a covert operation.

That operation began in 1953, when the Eisenhower administration authorized the Central Intelligence Agency to unleash a psychological warfare campaign that manipulated Guatemala’s own military to overthrow its democratically elected government.

CIA agents bribed members of Guatemala’s military. Anti-communist radio broadcasts and religious pronouncements about communist designs to destroy the nation’s Catholic church spread throughout the country.

Meanwhile, the U.S. armed anti-government organizations inside Guatemala and in neighboring countries to further undermine the Árbenz government’s morale.

And United Fruit enlisted public relations pioneer Edward Bernays to spread propaganda, not in Guatemala but in the United States. Bernays provided U.S. journalists with reports and texts that portrayed the Central American nation as a Soviet puppet.

These materials, including a film titled “Why the Kremlin Hates Bananas,” circulated thanks to sympathetic media outlets and members of Congress.

Destroying the revolution

Ultimately, the record shows, the CIA’s efforts prompted military officers to depose their elected leaders and install a more pro-U.S. regime led by Carlos Castillo Armas.

Guatemalans who opposed the reforms slaughtered labor leaders, politicians and others who had supported Árbenz and Arévalo. At least four dozen people died in the immediate aftermath, according to official reports. Local accounts recognized hundreds more deaths.

Military regimes ruled Guatemala for decades after this coup.

One dictator after another brutally repressed their opponents and fostered a climate of fear. Those conditions contributed to waves of emigration, including countless refugees, as well as some members of transnational gangs.

Blowback for bananas

To shore up its claims that what happened in Guatemala had nothing to do with bananas, exactly as the company’s propaganda insisted, the Eisenhower administration authorized an antitrust suit against United Fruit that had been temporarily halted during the operation so as not to cast further attention on the company.

This would be the first in a series of setbacks that would break up United Fruit by the mid-1980s. After a series of mergers, acquisitions and spinoffs, the only constant would be the ubiquitous Miss Chiquita logo stuck to the bananas the company sells.

And, according to many foreign policy experts, Guatemala has never recovered from the destruction of its democratic experiment due to corporate pressure.