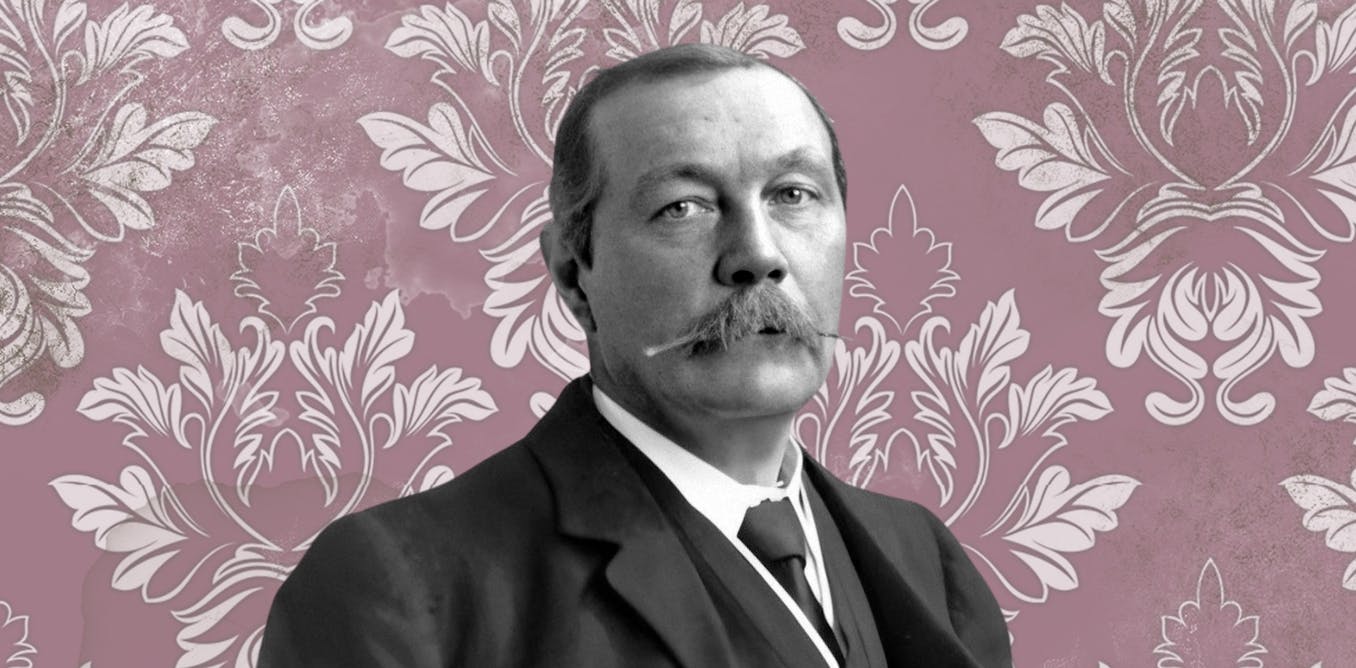

Arthur Conan Doyle was not just one of the world’s best crime fiction writers. He was a progressive wordsmith who brought light to controversial and taboo subjects. One of those taboo subjects was male vulnerability and mental health problems – a topic of personal significance to the author.

Doyle was a vulnerable child. His father, Charles, was an alcoholic, which led to financial troubles in the family. Charles was admitted to an asylum in 1881 and spent the next 12 years in various mental care establishments. So began Doyle’s interest in male vulnerability and mental health.

The character of Sherlock Holmes is a true expression of male vulnerability that does not equate it with weakness. Doyle does not represent Holmes as infallible, but as a man others can relate to – he battles with drug addiction, loneliness and depression. His genius thrives in part because of these vulnerabilities, not despite them.

Many of Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories examine male characters facing emotional catastrophe, betrayal or moral dilemmas. In works such as The Man with the Twisted Lip (1891), The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb (1892) and The Stockbroker’s Clerk (1894), Holmes’s male clients approach him with problems layered with emotional turmoil, fear and failure.

In The Man with the Twisted Lip, for example, a man named Neville St Clair hides his double life. He tells his family that he is a respectable entrepreneur going to London on business. In reality he is begging on the city streets. He lives this double life due to fear and shame over the inability to pay off his debts. “It was a long fight between my pride and the money,” he explains, “but the dollars won at last.”

Strand Magazine

“I would have endured imprisonment, ay, even execution, rather than have left my miserable secret as a family blot to my children,” St Clair says. In having his character consider execution to protect his and his family’s reputation, Doyle explored the societal expectations of Victorian masculinity and how men struggled with such pressures.

The Stockbroker’s Clerk also examines male suicide, as well as economic and professional anxieties. When Holmes reveals the crimes of Harry Pinner, the man attempts suicide rather than face prison.

In The Engineer’s Thumb, hydraulic engineer Victor is treated physically by Watson and mentally by Holmes. As Doyle writes: “Round one of his hands he had a handkerchief wrapped, which was mottled all over with bloodstains. He was young, not more than five-and-twenty, I should say, with a strong masculine face; but he was exceedingly pale and gave me the impression of a man who was suffering from some strong agitation, which it took all his strength of mind to control.”

The physical injury marks Victor as a victim of physical violence. Watson suggests that Victor is using all his mental capabilities to keep calm about his severe pain. Holmes treats Victor’s mind as he listens to his story: “Pray lie down there and make yourself absolutely at home. Tell us what you can, but stop when you are tired, and keep up your strength with a little stimulant.”

Holmes is a protector, a confidante and a comforter in this scene. He provides Victor with breakfast, induces him to lie down and offers him a stimulant (more than likely brandy).

The extremity of violence that Victor has endured has escalated to mental trauma. In having Holmes treat Victor’s mental trauma while Watson treats his physical pain, Doyle showed the importance psychological support for men of the age.

Holmes was a highly popular character. To contemporary readers, his drug use and dysfunctional clients were seen as markers of his genius rather than a reflection of the significant social issues that men faced during this period. But today, they offer a window into the mental struggles of Victorian men, and a point of connection between readers of the past and present.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.