(Washington, DC) – A new executive branch resolution broadening the scope for security agents’ use of firearms in Argentina runs counter to basic human rights standards and opens the door to abuse, Human Rights Watch said today.

On March 14, 2024, Security Minister Patricia Bullrich approved the resolution citing increased gang violence in the city of Rosario, Santa Fe province, which Human Rights Watch visited in late February. The resolution contains loopholes and ambiguities that could allow security officers to employ firearms in an unacceptably broad set of circumstances. It applies to all national security forces, including the national police and the national penitentiary service.

“People in Rosario and elsewhere in Argentina should be able to go about their daily lives without fear due to insecurity,” said Juanita Goebertus, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “To achieve that, the government should be strengthening judicial capacity and preventing gang recruitment, not opening the door to excessive use of force.”

The resolution is an extended version of another resolution that Bullrich passed in 2018, when she was also Security Minister. Human Rights Watch had called for its modification as it ran counter to international human rights standards.

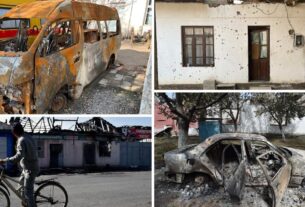

Rosario is the urban center with the highest rate of homicides in Argentina, five times higher than the average national rate. Its location, on the banks of a key waterway for regional trade and connected by land to Paraguay and Bolivia, makes it strategic for drug trafficking. For more than a decade, various local gangs have fought over control of the local drug trade. In the first two weeks of March, two taxi drivers, a bus driver, and a gas station employee were killed. Some analysts say the killings were possibly a countermove by gangs against the authorities’ measures to exert greater control in prisons.

When Human Rights Watch visited Rosario, provincial and municipal authorities, as well as judges, prosecutors, and experts on gang violence, emphasized the importance of strengthening judicial and prosecutorial capacities to investigate crimes by local gangs, their financing, and their connections with corrupt politicians. They also cited the need to prevent gang recruitment by improving education and job opportunities.

The resolution’s vague language is inconsistent with human rights standards that limit the use of firearms, Human Rights Watch said.

The resolution fails to distinguish between the use of firearms and the deliberately lethal use of firearms—that is, the distinction between shooting and shooting with the intent to kill. This is a key distinction because, even in those limited cases in which the use of firearms is justifiable, officers should generally not shoot to kill. Under the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, which the resolution cites but to which it fails to adhere, the intentional lethal use of firearms is permissible only “when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”

Moreover, the resolution allows federal security officers to use firearms when “non-violent means are ineffective,” without specifying that there are other means that should be employed before using firearms.

Under the UN Basic Principles, security officers may only employ firearms when “less extreme means,” including both non-violent and violent ones, are insufficient. This key provision recognizes that firearms are more likely to cause death or injury than other uses of force. Security forces may only use firearms when less lethal modes of force and non-violent means remain ineffective or without any promise of achieving the intended result.

The resolution undermines both administrative and judicial accountability for the use of firearms by security forces, Human Rights Watch said.

It provides that authorities cannot adopt “precautionary nor disciplinary measures” against an official “credibly” believed to have complied with the resolution, unless and until courts have issued a final criminal decision otherwise. This would make it impossible for authorities to discipline officers unless they have been convicted of a crime. It also eliminates the requirement, established in the 2018 resolution, that security forces “rapidly” prepare an administrative report after an officer uses a firearm causing injuries or death.

In a separate step, the Justice Ministry decided to carry out, starting in May, an adversarial system in criminal proceedings in the federal court system in Rosario, as part of a developing implementation of the system throughout the country. If effectively put in place, this change has the potential to accelerate criminal cases and more clearly distinguish between the functions of judges and prosecutors. However, authorities at the Attorney General’s Office and the Justice Ministry told Human Rights Watch that there were few, if any, additional resources available to implement the new system.

The administration of President Javier Milei should ensure adequate funding, resources, and training to ensure rights-respecting and effective investigations under the new system, Human Rights Watch said.