His death was announced in a statement by his longtime companion, Misa Shin, whose gallery in Tokyo recently had an exhibition of Mr. Isozaki’s designs. No cause was given.

Mr. Isozaki’s wide-ranging architectural interests defied easy labeling and his innovations could sometimes bring local objections, most notably clashes with the museum project overseers in Los Angeles in the 1980s that almost led to Mr. Isozaki walking away.

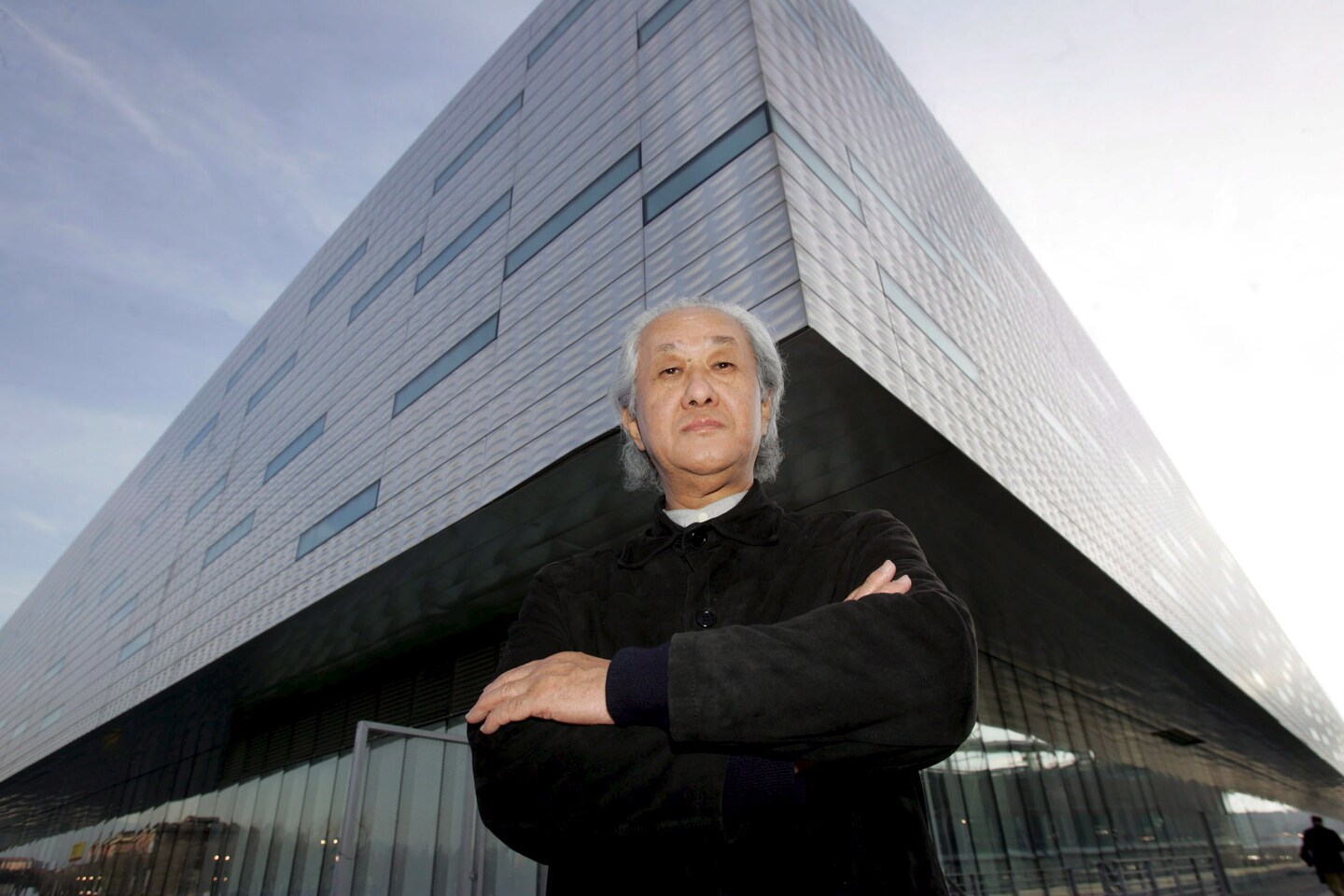

Even late in his career, his work was debated in architectural circles over why he had not been awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize — which he eventually received in 2019. “Isozaki demonstrated a worldwide vision that was ahead of his time and facilitated a dialogue between East and West,” wrote the Pritzker jurors.

“Originality of ideas is not important,” he told London’s Observer newspaper in 1991. “We can borrow anything.”

Mr. Isozaki’s more than 100 major commissions around the world carried no signature elements. He found inspiration in the geometric austerity of modernist and Brutalist schools in projects such as the Oita Prefectural Library (now Oita Art Plaza) in his hometown in Japan or the glass-cube facade of Barcelona’s D38 office park.

He could also draw from the sinuous contours of nature such as the reptilian curves of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing or find playful touches. He added loops resembling Mickey Mouse ears to the entrance of the Team Disney Building in Orlando, and made the Fujimi Country Club — a golfing hot spot in Oita — in the shape of a question mark as if to ponder: Why did Japan become so obsessed with golf?

On a rocky outcrop in Spain’s northwest Galicia region, Mr. Isozaki’s Domus: La Casa del Hombre, a science museum, mixes fortresslike walls with a shield-shaped cover as if to protect from the maritime gales.

But a guiding principle connecting it all, he said, was having the empty space of the structure as much part of the design as what is constructed. The concept in Japanese is described as “ma,” the power and possibility of a pause or spatial emptiness. He often called it an essential part of “Japan-ness.”

In 1945, when Mr. Isozaki was 14, he was at his home in Oita — midway between Hiroshima and Nagasaki — when the atomic bombs fell. Oita was spared the direct devastation, but the images of the two razed cities left Mr. Isozaki wondering how they could ever be rebuilt.

“So, my first experience of architecture was the void of architecture,” he said.

The war never really left him. His theoretic concepts on urban design had impermanence as a central theme — the idea that cities rise and fall and are always in flux. Several 1968 drawings and photo collages for the Milan Triennial included “Re-Ruined Hiroshima,” imagining domed communities atop a nuclear wasteland.

To rise above Tokyo’s teeming streets, Mr. Isozaki imaged in 1962 “The City in the Air,” pod-style apartments on an ever-evolving forestlike canopy. Mr. Isozaki envisioned mimicking cellular growth in biology, rather than relying solely on technology, as a future of architecture. (A design based on “The City in the Air” was proposed for the Qatar National Library, but the project did not move ahead.)

“When I think of the hollow sound of the slogans for building, renewing and improving cities — in reality the political propping-up of the metropolis — I come to think in terms of destruction as the only reality,” he wrote in a 1962 essay “City Demolition Industry, Inc.”

Aaron Betsky, director of School of Architecture and Design at Virginia Tech, described Mr. Isozaki as a realist in the most literal sense — acknowledging the “passing of all things.”

“More than anything else,” Betsky wrote in the journal Architect in 2019, “he has produced memento mori for the modern age, reminding us that all our vaulting ambition will someday be swept away, as we will be, and thus we must examine, cherish, and question our own productions.”

Arata Isozaki was born on July 23, 1931, in Oita on Japan’s southern Kyushu region, where his father ran a prominent transport company and relaxed by writing haiku. One translation of Arata is “new field,” which Mr. Isozaki said could have reflected his father’s desire to bring more modern approaches to his poetry.

Mr. Isozaki studied architecture at the University of Tokyo, receiving an undergraduate degree in 1954 and doctorate in 1961. He became a protege of renowned modernist architect Kenzo Tange before opening his own office in Tokyo in 1963.

Mr. Isozaki’s early connections to Western culture were mostly through his interest in jazz and playwrights including Arthur Miller. A trip to Europe in the early 1960s was a pivotal introduction to a mix of traditional and modern design as the continent rebuilt from the war. In Rome, he began a lifelong fascination with the marble statue “Sleeping Hermaphroditus” at the Borghese Gallery. He said he was transfixed by its tranquility and ambiguity.

His marriage in 1972 to sculptor Aiko Miyawaki, who had lived in Paris for years, brought him deeper into Western art and design circles, including artist Man Ray and experimental composer John Cage.

Mr. Isozaki’s projects were only within Japan until 1980, when he was commissioned to build the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. His vision of grand halls with chiaroscuro interplay of sunlight and shadow clashed with some members of the oversight board. Its director, business magnate and art collector Max Palevsky, said it lacked “sophistication.”

Mr. Isozaki said was ready to “quit or be fired” rather than make too many concessions. Los Angeles-based architect Frank Gehry — who would later design the city’s Cubist-style Walt Disney Concert Hall — persuaded Mr. Isozaki to court support from other museum trustees to find a way forward.

In the end, Mr. Isozaki’s ideas remained mostly intact, and the museum opened in 1986 as a collection of galleries in bold red Indian sandstone lit by pyramid-shaped skylights. On sunny days, the exterior shines with a light-and-dark pop of an Edward Hopper painting.

Some critics, such as Paul Goldberger at the New York Times, took issue with Mr. Isozaki’s design of having visitors descend stairs to approach the galleries. “It feels a bit like going into a basement to view art,” he wrote.

But architecture critic Jed Perl described the light in the galleries as “beatific, serene.” Ironically, the skylights were later covered and replaced by spotlights to protect the artworks; museum curators have explored options to reopen them.

Mr. Isozaki’s wife died in 2014. He is survived by a son, Hiroshi; a grandson and a sister.

During the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, a hub of activity for journalists and officials was Mr. Isozaki’s Qatar National Convention Center in Doha. The roof is buttressed by massive trunks and branches intended to resemble the country’s desert Sidra tree.

“A design should be first practical. It should work,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “But to be architecture, it also must be conceptual.”