How much can the written records of ancient civilisations tell us about the animals they lived alongside? Our latest research, based on the venomous snakes described in an ancient Egyptian papyrus, suggests more than you might think. A much more diverse range of snakes than we’d imagined lived in the land of the pharaohs – which also explains why these Egyptian authors were so preoccupied with treating snakebites!

Like cave paintings, texts from early in recorded history often describe wild animals the writers knew. They can provide some remarkable details, but identifying the species involved can still be hard. For instance, the ancient Egyptian document called the Brooklyn Papyrus, dating back to around 660-330BC but likely a copy of a much older document, lists different kinds of snake known at the time, the effects of their bites, and their treatment.

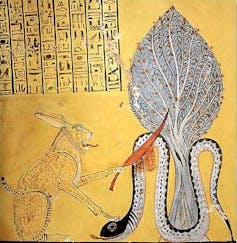

As well as the symptoms of the bite, the papyrus also describes the deity associated with the snake, or whose intervention might save the patient. The bite of the “great snake of Apophis” (a god who took the form of a snake), for example, was described as causing rapid death. Readers were also warned that this snake had not the usual two fangs but four, still a rare feature for a snake today.

The venomous snakes described in the Brooklyn Papyrus are diverse: 37 species are listed, of which the descriptions for 13 have been lost. Today, the area of ancient Egypt is home to far fewer species. This has led to much speculation among researchers as to which species are being described.

The four-fanged snake

For the great snake of Apophis, no reasonable contender currently lives within ancient Egypt’s borders. Like most of the venomous snakes that cause the majority of the world’s snakebite deaths, the vipers and cobras now found in Egypt have just two fangs, one in each upper jaw bone. In snakes, the jaw bones on the two sides are separated and move independently, unlike in mammals.

W. Wüster

The nearest modern snake that often has four fangs is the boomslang (Disopholidus typus) from the sub-Saharan African savannas, now only found more than 400 miles (650km) south of present-day Egypt. Its venom can make the victim bleed from every orifice and cause a lethal brain haemorrhage. Could the snake of Apophis be an early, detailed description of a boomslang? And if so, how did the ancient Egyptians encounter a snake that now lives so far south of their borders?

To find out, our masters student Elysha McBride used a statistical model called climate niche modelling to explore how the ranges of various African and Levantine (eastern Mediterranean) snakes have changed through time.

Niche modelling reconstructs the conditions in which a species lives, and identifies parts of the planet that offer similar conditions. Once the model has been taught to recognise places that are suitable today, we can add in maps of past climate conditions. It then produces a map showing all the places where that species might have been able to live in the past.

On the trail of ancient snakes

Our study shows the much more humid climates of early ancient Egypt would have supported many snakes that don’t live there today. We focused on ten species from the African tropics, the Maghreb region of north Africa and the Middle East that might match the papyrus’s descriptions. These include some of Africa’s most notorious venomous snakes such as the black mamba, puff adder and boomslang.

We found that nine of our ten species could probably once have lived in ancient Egypt. Many could have occupied the southern and southeastern parts of the country as it then was – modern northern Sudan and the Red Sea coast. Others might have lived in the fertile, vegetated Nile valley or along the northern coast. For instance, boomslangs might have lived along the Red Sea coast in places that 4,000 years ago would have been part of Egypt.

Similarly, one entry of the Brooklyn Papyrus describes a snake “patterned like a quail” that “hisses like a goldsmith’s bellows”. The puff adder (Bitis arietans) would fit this description, but currently lives only south of Khartoum in Sudan and in northern Eritrea. Again, our models suggest that this species’ range would once have extended much further north.

Since the period we modelled, a lot has changed. Drying of the climate and desertification had set in about 4,200 years ago, but perhaps not uniformly. In the Nile valley and along the coast, for instance, farming and irrigation might have slowed the drying and allowed many species to persist into historical times. This implies that many more venomous snakes we only know from elsewhere might have been in Egypt at the time of the pharaohs.

Our study shows how enlightening it can be when we combine ancient texts with modern technology. Even a fanciful or imprecise ancient description can be highly informative. Modelling modern species’ ancient ranges can teach us a lot about how our ancestors’ ecosystems changed as a result of environmental change. We can use this information to understand the impact of their interactions with the wildlife around them.