The water infrastructure politics of eThekwini, the municipality that includes the city of Durban, have been splashed across the digital pages of South Africa’s news outlets in recent years.

They’ve covered the 2022 floods that damaged kilometres of pipes, water tanker purchases as a response to increasing water scarcity, and the disconnection of residential water storage tanks from municipal pipes to cope with leaky infrastructure. Like other South African municipalities, eThekwini has fallen behind on maintaining its piped water infrastructure and has looked to stopgap solutions.

The city’s water politics has a long history. Some of the infrastructure issues can be traced back to the mid-1800s, when it was a British imperial port.

I’m a historian with an interest in coastal communities and urban life. As part of my work on water as a public health concern in colonial cities, I spent months in the Durban Archives Repository, going through correspondence, reports, business contracts, newspaper clippings and town council minutes.

The records revealed how the system of colonial-era water infrastructure worked – and for whom.

The first water technologies in Durban were British-styled wells. Anyone could use them, for free. They brought people of different origins and class together for practical purposes but also created anxiety about social difference. For colonial officials, the public had to follow British standards or lose access to the infrastructure altogether. They created Durban’s first water-policing system, purportedly for better public health and conservation. While wealthier and white people eventually came to rely on piped water, poorer and black (Zulu and Indian) people were excluded.

This system formed the basis for the uneven access to water that today’s residents experience. People still depend on private water infrastructure as the municipal system struggles.

Nineteenth-century infrastructure

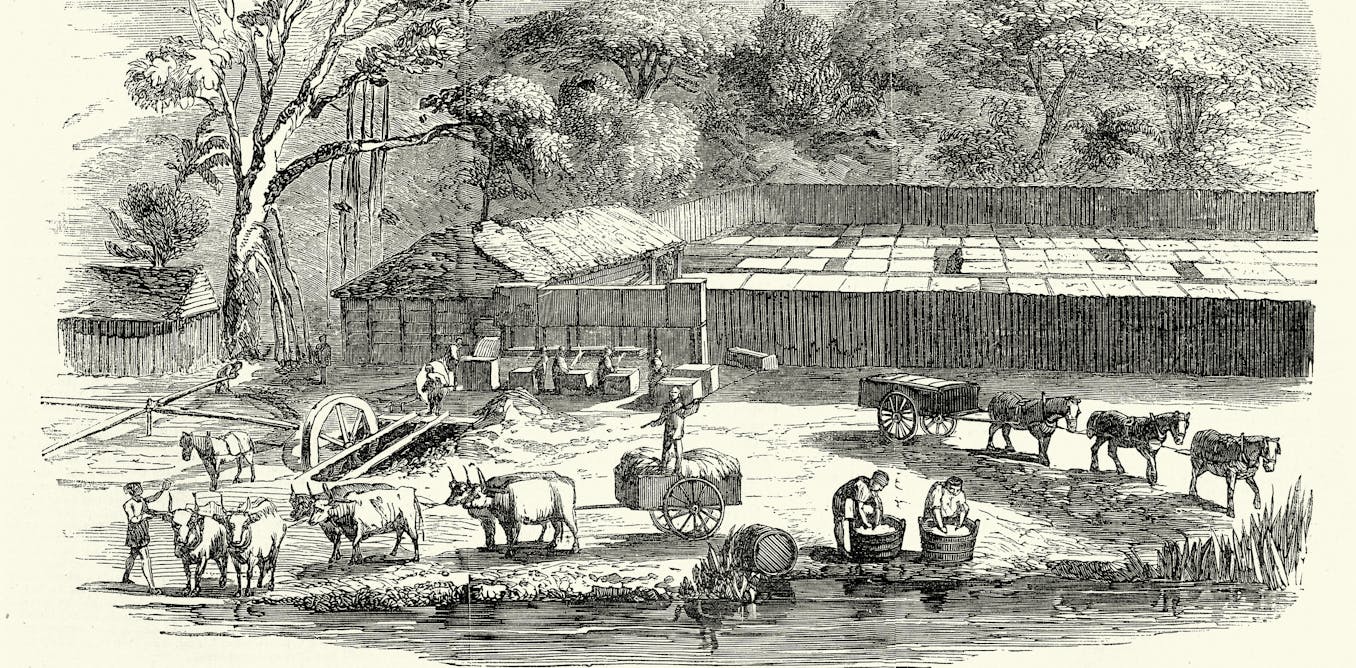

Founded by British traders as Port Natal in 1824, the colonial borough of Durban depended on stand-alone water infrastructures from the beginning. Brick and cement wells were the first technologies from which residents drew water, since they were easy to build and maintain. Most wells had either a bucket or a pump attached to them. Pumps attached to wells became common after the borough made most wells publicly available in the mid-1850s.

Water tanks, on the other hand, were private technologies which mainly lay underground. Only wealthier households and businesses could afford to build them. They became prominent in the 1870s.

It’s hard to know exactly how many of these infrastructures existed in total. By the 1870s, though, official reports indicate that about 18 public wells and pumps across the town served the bulk of the town’s approximately 20,000 inhabitants.

Piped water came to Durban in the 1880s, supplied initially by the spring at Curries Fountain. In 1889, the city’s laws were extended to cover private tanks that were filled from the municipal pipes. Even so, much of the population still relied on standalone infrastructures for water supplies.

As time went by, conflicts began to brew. The rising population placed a strain on these stand-alone infrastructures, which offered varying amounts of water depending on rainfall patterns. Arguments sparked when a community drew too much water or polluted a well, creating a local water scarcity.

Clashes and restrictions

White colonists blamed much of the water scarcity and contamination on African labourers who worked as household or business servants, sanitary workers and launderers. These positions demanded a close relationship with fresh water collection and use, which meant African labourers became the main users of wells, pumps and tanks.

Labourers did not always use water technologies according to colonial expectations, however. Local people were accustomed to using open water sources like rivers and streams, not restrictive iron and brick infrastructures. So, they modified their traditional work at open sources, like washing objects and produce, to the new technologies they had to use.

That sometimes created problems, according to the archive records. They accidentally broke handles and chains when pumping too quickly. They drew water from tanks without using a filter, which was officially perceived as a disease risk. They publicly washed clothing, bodies and food at wells, where the dirty wash water flowed back into the enclosed water supply.

Colonists exploited this situation to place restrictions on how labourers could use stand-alone water infrastructures. Borough officials crafted new laws that forced colonised residents to conform with British standards. They punished those who did not comply with fines, verbal lashings and even jail time.

Durban was part of a colonial system predicated on white supremacy. The government sought to maintain segregation between white colonists and African and South Asian residents. So, it imbued its water technology regulations with the notion that some water management actions – British – were “healthier” than others, namely African and South Asian. If someone used a technology contrary to British standards, then they faced restricted access to public technologies and the water they provided.

Water system legacy

Stand-alone water infrastructures still exist across eThekwini. Many residents of informal settlements and formerly racially segregated areas remain officially unconnected with municipal pipes. They instead depend on local wells, pumps and illegal individualised connections. An increasing number of households are investing in water tanks as the municipal water system becomes more unreliable.

Things have, of course, changed since the 19th century. However, the municipality continues to require residents to use these technologies within regulatory boundaries if residents want to maintain access to them. Cutting off municipal water supply to private storage tanks is an example.

Infrastructural stopgaps further expose a water system that was never meant to supply every resident equitably and without restriction. These actions tell us that today’s officials have inherited and inadvertently continue a water system that was meant to exclude more than include, to punish more than teach, to restrict more than provide.

![]()

Kristin Brig receives funding from the US Fulbright Program, the US National Science Foundation (NSF), and Johns Hopkins University.