An ever more unequal society loses its links to democracy. Wealth is good. Excess wealth distorts. Those were the lessons of the last years of the Roman republic 2000 years ago. They are still lessons today.

Seven years on from Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign it’s easy to forget that his populism came from the Latin textbooks. When Trump was riding high, he followed closely (likely not knowingly) the populists of Republican Rome. Trump was no Julius Caesar, except maybe in his dreams, but his electoral pitch did owe much to Caesar’s uncle, Gaius Marius, Rome’s first ‘man of the people’ who won election after election, a record seven consulships, by attacking the elitism of his enemies and vaunting his own trustworthiness to the poor and left behind. When Trump used his purported wealth to prove his selflessness in seeking office (and in attacking Hillary Clinton as the client of the plutocrats) these were tactics that both Marius and Caesar would have instantly recognized.

In 2022 the Latin lesson continues. Early Rome prospered not because it was an egalitarian democracy but because it was generally more equal, open, and democratic than its rivals, For instance, freeing slaves when the Greeks thought that a step too far. But throughout the first century BCE Rome’s intermittent civil wars between its ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ left one man eventually as the wealthiest politician of his time, maybe of all time. His name was Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Like Trump, Crassus made his first fortune in property, redeveloping land taken from the war’s losers, building flashy mansions for the winners. He went on to make a genuine massive fortune from mining and banking. He is best known today as the villain who crucified Kirk Douglas in Stanley Kubrick’s film, Spartacus, but, for all the gruesome theatre of crosses along the Appian Way, winning a slave war was little more than a sideshow for Crassus. He had created for himself a new kind of power, the permanent kind, the power to use money behind the scenes, pulling the strings of whichever puppet seemed to be in charge. He was the first tycoon.

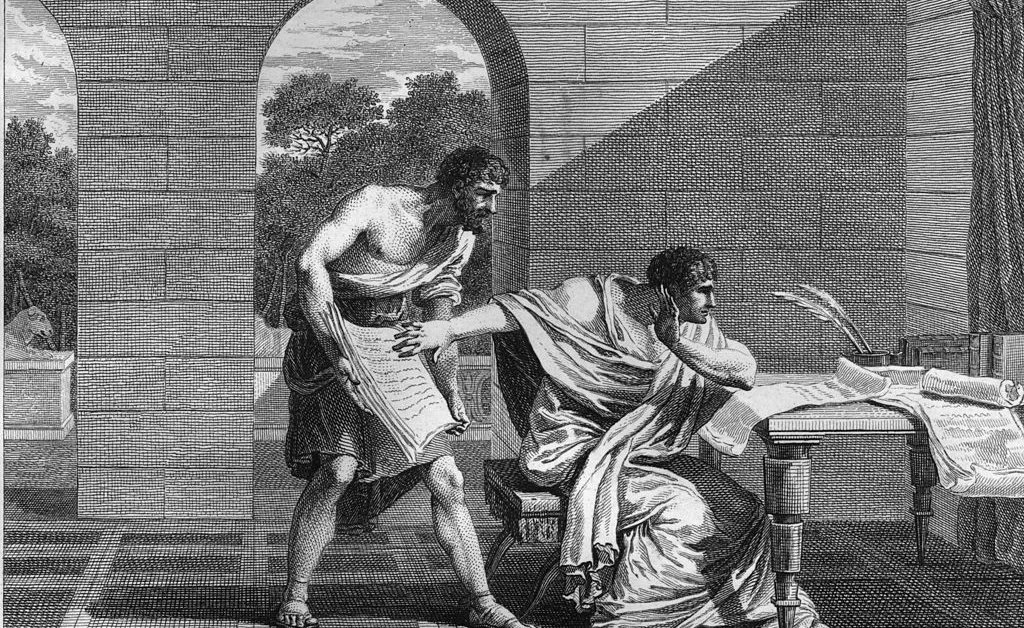

Even Caesar himself was Crassus’s puppet at the beginning of his career. Crassus financed Caesar’s election campaigns, making sure at a stupendous cost that Caesar became pontifex maximus, the chief priest, the only man with a house in the Roman Forum. Once Crassus had helped Caesar to his military commands in Gaul, he watched his protégé’s back in Rome, bribing, moneylending, making speeches, and calling in favours in order to ensure, for a while at least, that Caesar became a useful counterweight to Crassus’s lifetime rival, Pompey the Great.

Caesar and Pompey both distorted the balance of Roman politics with vast wealth won, stolen if critics were frank, from conquered kings in Rome’s expanding empire. Crassus kept his place in this three-man oligarchy called the ‘Three Headed Monster’ by continuing to use his financial power to balance the influence of his more acclaimed military partners. Senators wore black to show their objection to this change to the traditional system of checks and balances but were powerless against the onslaught of against the dominance of the super-rich.

Gradually Crassus came to see that wealth alone would not be enough to maintain his place at the three-legged top table of Rome. Caesar, rich from Gaul and protected by loyal legions, did not need Crassus’s money anymore. Pompey, after a triumph through the streets of Rome parading giant golden statues and his own head in pearls, was probably for a time even richer than Crassus.

So, the man whose power rested on his reputation for wealth decided on a last campaign to keep himself up with Caesar and Pompey. He moved onto his rivals’ turf, trained personal legions as he had trained slaves for his building sites, and prepared to take on a neighbour in war. In 53 BCE, twenty years after the Spartacus rebellion, his fellow oligarchs allowed their colleague to plan an invasion of Parthia, a sprawling empire east of the Euphrates.

But Crassus, for all his commercial and organisational skill, was ill prepared. He was accountable only to Caesar and Pompey. The traditional senatorial systems of diplomacy and intelligence had broken down before the power of money. Crassus knew very little about his Parthian adversaries and, like Trump’s friend, Vladimir Putin, in the Ukraine today, he thought he knew much more than he did.

Crassus expected to face legionaries like his own led by a deal-making pragmatist like himself. Instead, his army faced a swirling mass of archers on ponies, their quivers perpetually replenished from a camel train, a whole new weapon system. Trying to negotiate a retreat, he squabbled over a horse. His head was cut down on to the sand, his mouth filled with molten gold to mark the greed that all the Parthians knew him for.

Back in Rome, the two remaining heads of the three-headed monster were soon at each other’s throats. Caesar, on the side of the populists, defeated Pompey, leader of the establishment, and ruled briefly as a dictator before his assassination on the Ides of March, 44 BCE. His chosen heir, Octavian, won a final civil war before establishing a system of one-man rule, supported by frail, almost fake, democratic institutions, which survived for centuries.

More Must-Reads From TIME