Neanderthals have long been the subject of intense scientific debate. This is largely because we still lack clear answers to some of the big questions about their existence and supposed disappearance.

One of the latest developments is a recent study from the University of Michigan, published in the journal Science Advances. It proposes that Neanderthals went extinct for astrophysical reasons.

The work was led by Agnit Mukhopadhyay, an expert in space physics, a discipline that studies natural plasmas, especially those found within our own solar system. Plasma is the state of matter that dominates the universe: the Sun and stars are huge balls of plasma, as are the northern lights.

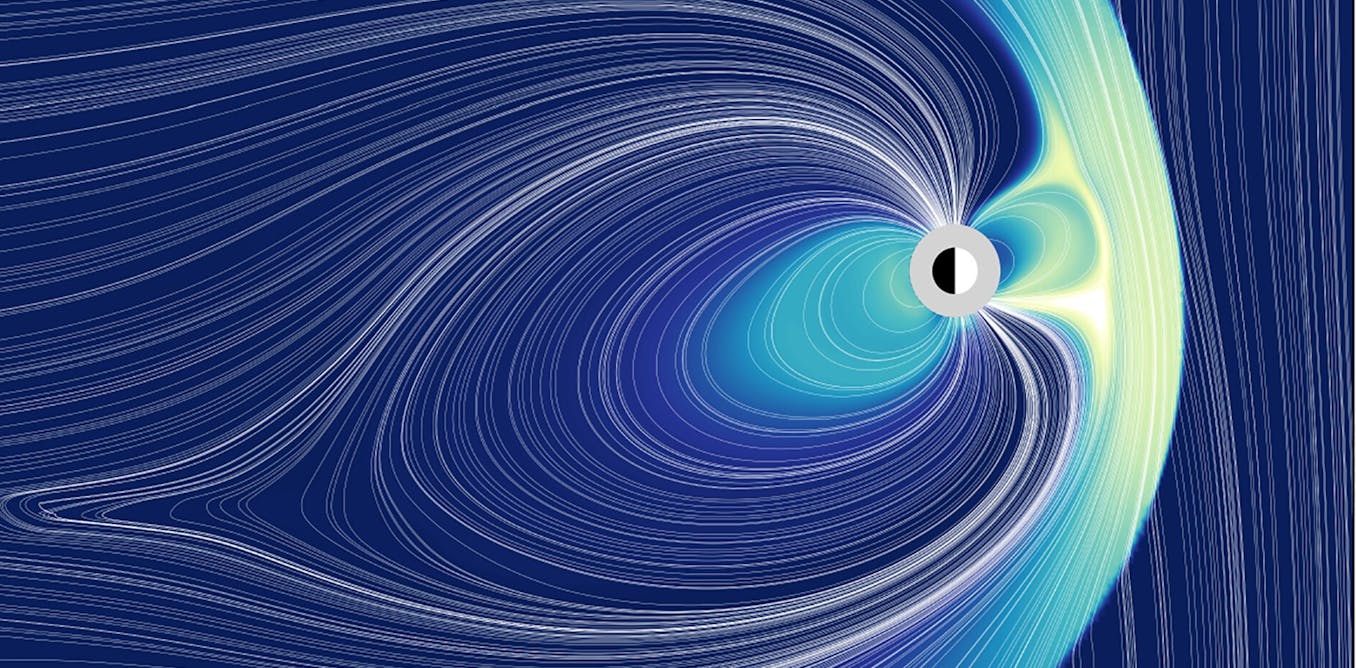

Mukhopadhyay’s research suggests that a shift in the Earth’s magnetic poles around 41,000 years ago, known as the Laschamp event, may have contributed to the extinction of Neanderthals.

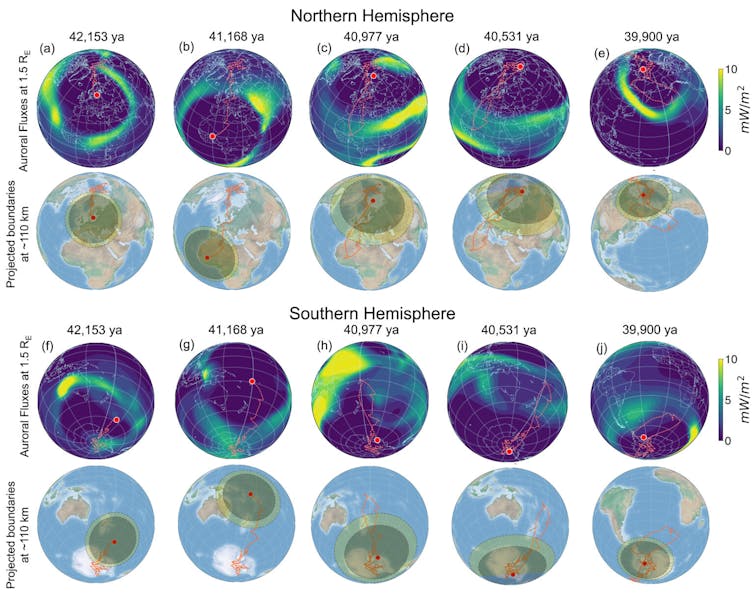

Agnit Mukhopadhyay, University of Michigan/Science Advance, CC BY

According to his work, the extreme weakening of the Earth’s magnetic field during that event allowed for greater penetration of cosmic and ultraviolet radiation. This would have generated more aggressive environmental conditions that Neanderthals could not withstand, giving our own species, Homo sapiens, an edge.

Homo sapiens‘ advantage

In this context, sapiens would have had an advantage over Neanderthals thanks to their presumed use of close-fitting clothing, ochre – a mineral with protective properties against the sun – and taking shelter in caves. Caves which, by the way, on numerous occasions were inhabited by both Neanderthals and our own species.

The hypothesis is interesting, and is based on innovative three-dimensional models of the Earth’s geospatial system during this period. However, as with many hypotheses that attempt to explain complex phenomena on the basis of a single variable, its scope and some of the assumptions on which it is based need to be examined more closely.

Agnit Mukhopadhyay, Universidad de Michigan., CC BY

Tight-fitting clothes and sewing needles

One of the pillars of this hypothesis is that Neanderthals did not wear tight-fitting clothing, and would therefore have been more exposed to the harmful effects of solar radiation.

It is true that sewing needles have not been definitvely linked to Neanderthals. The first needles documented in Eurasia are associated with either Denisovan or sapiens populations around 50,000 years ago, and in western Europe they did not appear until around 23,000 years ago. But this does not mean that Neanderthals did not wear clothing.

In fact, the Homo sapiens who lived during episodes of extreme cold (such as the Heinrich 4 event, which occurred some 39,600 years ago) did not have sewing needles either, but they did have enough technology to make garments, and possibly tents and footwear.

There is ample archaeological evidence of Neanderthals processing hides, such as the systematic use of scrapers and other tools associated with the tanning process.

However, the use of fur or clothing has much older origins. In fact, the genetic study of lice has revealed that humans were already wearing clothing at least 200,000 years ago.

Furthermore, in cold environments such as those they inhabited in Europe, it would have been unfeasible to survive without some form of body protection. Even if they did not have needles, it is very plausible that they used alternative systems such as ligatures or bone splinters to adapt animal hides to the body. The absence of needles should not be confused with the absence of functional clothing.

Prehistoric sunscreen

The study also highlights the use of ochre by Homo sapiens, which it says offered protection against solar radiation.

Although experiments have been carried out to demonstrate certain blocking capacities of ochre against ultraviolet (UV) rays, its use by human populations is not limited to a single group. In fact, evidence of pigment use during the same period has been found in Africa, the Near East and the Iberian Peninsula, and among different human lineages.

The use of ochre has been documented in Neanderthal contexts for more than 100,000 years, both in Europe and in the Levant. Its application may have had multiple purposes: symbolic, therapeutic, cosmetic, healing, and even an insect repellent.

João Zilhão.

There are no solid grounds for claiming that its use for protective purposes was exclusive to Homo sapiens, especially when both species shared spaces and technologies for millennia. Nor can we be sure that it was used as a protective sunscreen.

Sapiens outnumbered Neanderthals

One of the most significant factors may have been the marked difference in population size. There were fewer Neanderthals, meaning they would have been assimilated by the much more numerous populations of Homo sapiens.

This assimilation is reflected in the DNA of current populations, suggesting that, rather than becoming extinct, Neanderthals were absorbed into the evolutionary process.

Technology also played a part– as far as we know, Neanderthals did not use hunting weapons at a distance.

The invention and use of projectiles associated with hunting activities – first in stone and later in hard animal materials – appear to be an innovation specific to Homo sapiens. Their development may have given them an adaptive advantage in open environments, and a greater capacity to exploit different prey and environments.

Read more:

Neanderthals died out 40,000 years ago, but there has never been more of their DNA on Earth

No scientific evidence

Associating the Neanderthal “extinction” to their supposed failure to adapt to increased solar radiation during the Laschamp excursion oversimplifies a phenomenon that remains the subject of heated debate.

Put simply, the archaeological record does not support Mukhopadhyay’s hypothesis. There is no evidence of an abrupt demographic collapse coinciding with this geomagnetic event, nor of a widespread catastrophic impact on other human or animal species.

Moreover, if solar radiation had been such a determining factor, one would expect high mortality also among populations of sapiens that did not wear tight clothing or live in caves (in warm regions of Africa, for instance). As far as we know, this did not happen.

When trying to explain the disappearance of Neanderthals, it is vital that we integrate multiple lines of archaeological, paleoanthropological and genetic evidence.

These humans were not simply victims of their own technological clumsiness or of a hostile environment that they failed to cope with. They were an adaptive and culturally complex species that, for more than 300,000 years, survived multiple climatic changes – including other geomagnetic shifts such as the Blake event, which occurred about 120,000 years ago. Neanderthals developed sophisticated tools, dominated vast territories and shared many more traits with us than was assumed for decades.

So did the magnetic reversal of the Earth’s magnetic poles wipe out the Neanderthals? The answer is: probably not.