In Catalonia’s elections, held on 12 May, pro-independence parties lost the parliamentary majority that had allowed them to govern since 2015. It was their first electoral defeat in decades.

They lost to the Socialists’ Party of Catalonia (PSC, Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya), the Catalan wing of Spain’s ruling PSOE, with former health minister Salvador Illa expected to take over as president by the end of August.

This shift in public opinion begs the twin questions of whether the recent push for Catalan independence (known as the procés) has finally ended, and whether the electoral defeat of pro-independence parties means that the Catalan independence movement itself has reached an end.

A decade-long push for independence

While the Catalan independence movement dates back centuries, the procés is the name given to the surge of political support for this goal over the last 14 years or so. Its origins can be traced back to July 2010, when a Spanish Constitutional Court ruling annulled and amended some essential aspects of the new Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, which the Catalan people had previously backed in a June 2006 referendum.

Up to then, pro-independence parties had taken only a minority of the vote share (less than 20%), and their influence on Catalan politics was limited. However, from 2010 onwards, support for them grew exponentially, reaching a peak of 48% in the 2015 elections.

This new panorama marked the beginning of a profound change in the Catalan political system, as the then dominant moderate alliance Convergence and Union (CiU) began to lose electoral ground. The alliance broke up altogether when one of its member parties, Convergence (Convergència), was forced to adopt a stronger pro-independence stance after losing 10 seats in the 2012 elections, forming a new alliance with the pro-independence Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya).

Author’s own, data from Parliament of Catalonia

October 2017 – a timeline of the procés

With hardline pro-independence leader Carles Puigdemont at the helm, the 2015 electoral term saw independence take priority on Catalonia’s political agenda.

At the height of the procés (September-October 2017), the Catalan Parliament approved the Llei de referèndum d’autodeterminació (Law on the Referendum on Self Determination) and the Llei de transitorietat jurídica i fundacional de la República (Law on the Legal and Foundational Transition of the Republic) on 6 and 8 September, respectively. Both aimed to legally pave the way for Catalonia to break away from Spain.

On 20 September, the Guardia Civil searched various Catalan Government offices. This provoked an immediate reaction from the Catalan public, who gathered outside the gates of the region’s Ministry of Economy.

Days later, the main civilian leaders of the pro-independence movement – Jordi Sánchez and Jordi Cuixart – were charged with the crime of sedition.

On 1 October 2017, the now infamous referendum on self determination in Catalonia was held, with just over two million votes cast. Throughout the day there were multiple incidents of serious violence, as police used excessive force to seize ballot boxes and prevent voting.

Read more:

Spanish government crushes Catalan independence dreams – at a high price

On 27 October, the Catalan Parliament passed the declaration of Catalan independence. On the same day, Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy, with prior authorisation from the Senate, enacted Article 155 of the Constitution, immediately calling a snap election in the region.

On 29 October, several members of the Catalan government fled to Belgium. Shortly afterwards, the pro-independence leaders who remained in Catalonia were arrested and charged with the crimes of rebellion, sedition and embezzlement.

The rise of the Socialists’ Party of Catalonia

The 2024 elections have marked a radical shift in Catalonia’s political landscape. The PSC won by a comfortable margin, while support for pro-independence parties plummeted – in the 2015, 2017 and 2021 elections, they won absolute majorities of more than 70 MPs, but in 2024 they achieved a combined total of just 59 MPs.

So, does this mean the procés has come to an end?

Understood as a political movement, with specific actors pursuing the singular, unilateral goal of Catalan independence, the procés has indeed ended. More generally, it has ceased to be a political priority – continued confrontation with the Spanish state has been unproductive for Catalonia and politically disruptive for Spain. Indeed, Spain’s far right owes much of its success to a harsh rhetoric of opposition to Catalan independence, including proposals to ban separatist parties outright.

Dialogue and amnesty

The pardons granted to Catalan separatists through the recently enacted Amnesty Law have reduced tensions and made it possible to channel conflict off the streets and back into the political arena.

In recent years, Catalonia’s current president Pere Aragonès, of ERC, has pursued a pragmatic approach of opening up channels of communication and negotiation between regional and national governments. Specific mechanisms have been set up to to normalise political relations between Catalonia and Spain: the roundtable for dialogue between the Spanish and Catalan Generalitat, and the Generalitat-State Bilateral Commission.

Read more:

The Spanish amnesty law for Catalonia separatists, explained

Pro-independence politics isn’t going anywhere

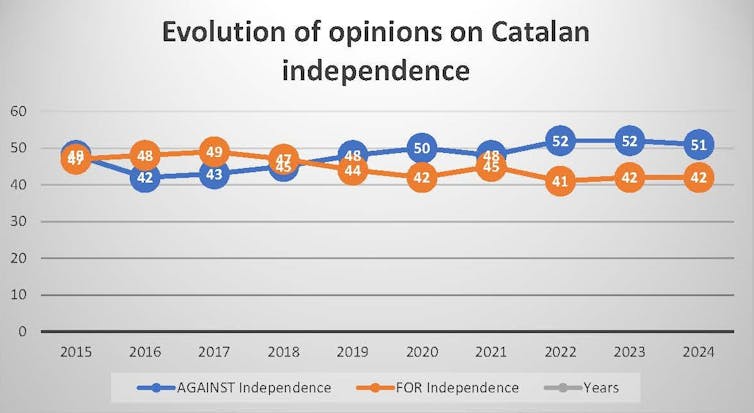

While the procés may be drawing to a close, the electoral defeat suffered by pro-independence parties in no way spells the end of the Catalan independence movement. As the table beneath shows, since the 2015 elections, pro-independence groupings have received a higher vote share than national, “constitutionalist” parties. The most recent elections – where pro-indepdendence parties garnered 39.4% of the vote share – are the only exception.

Author’s own

Political fatigue and apathy among part of the Catalan electorate in the 2021 and 2024 elections has been reflected in a sharp increase in abstention, which has particularly affected pro-independence parties.

Author’s own, made with data from Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió, Generalitat de Catalunya, 2015-2024.

While the procés may have ended, the independence movement is still very much alive and kicking – support for independence has dropped, but even at its current low ebb it has the backing of 42% of Catalonia’s population. This ingrained, structural phenomenon is unlikely to disappear any time soon, but it can be redirected into productive dialogue and negotiation.