(Johannesburg) – The conviction and sentencing of a leading opposition member to 18 months in prison with hard labor will have a broad chilling effect on the right to freedom of expression in Zambia, Human Rights Watch said today.

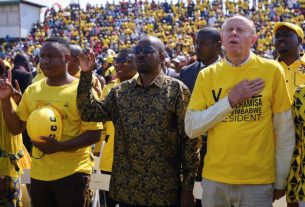

Raphael Nakacinda, secretary general of the main opposition party, Patriotic Front, was sentenced on May 17, 2024, for his 2021 remarks “defaming the president,” a criminal offense that the president abolished in 2022. President Hakainde Hichilema had earlier said that the law on criminal defamation of the president “inhibits the growth of democracy and good governance, impedes human rights and basic freedoms.”

“Sending a leading opposition figure to prison under a law that previous administrations have notoriously used to silence critics is a blot on President Hichilema’s record,” said Idriss Ali Nassah, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The administration should quash Raphael Nakacinda’s conviction, release him, and stop prosecuting political opponents and others under this revoked law.”

In December 2021, Nakacinda alleged that President Hichilema had summoned judges to his residence to intimidate and coerce them into passing judgments favorable to him in legal battles with the Patriotic Front. Hichilema’s spokesperson dismissed the allegation as “contemptuous,” and said that “law enforcement agencies must not hesitate to hold accountable those who will abuse basic constitutional freedoms to peddle malicious and baseless attacks against other members of the public.”

Nakacinda, 43, was sentenced under section 69 of Zambia’s penal code, which had made it a criminal offense for “any person who, with intent to bring the President into hatred, ridicule or contempt, publishes any defamatory or insulting matter, whether by writing, print, word of mouth or in any other manner.” Those convicted face up to three years in prison.

In 2022, President Hichilema assented to Penal Code (Amendment) Bill No. 25, which repealed section 69, effectively abolishing the crime of defaming the president. He later wrote on X (formerly Twitter) that he had repealed the law as part of his commitment to democracy as it is “the democratic right of every citizen to be able to exercise their rights.” According to media reports, the magistrate who sentenced Nakacinda said that she was aware that the law had been repealed but still convicted Nakacinda as a deterrence to others.

In Zambia, the charge of criminal defamation of the president has been used for decades to prosecute critics of the government and journalists. When elected president in 2021, Hichilema promised to amend laws that inhibit basic human rights and freedoms.

However, the media reported that in 2022 alone, at least 12 perceived critics and opponents of Hichilema had been arrested for insulting the president, some multiple times. For example, in September 2022 the authorities arrested Sean Tembo, president of a smaller opposition party, Patriots for Economic Progress, and charged him with “defaming the president.” He is facing another two charges for using insulting language against the president, a separate offense under section 179 of the penal code, in August and October 2023, to which he pleaded not guilty.

These charges raise concerns that President Hichilema intends to use the law, like his predecessors, to stifle critical voices and deter criticism, Human Rights Watch said.

The Chapter One Foundation, which promotes constitutionalism and the rule of law in Zambia, told Human Rights Watch that although the provisions on defaming the president were repealed, the repeal did not apply retrogressively. Cases that had been initiated before the repeal, such as Nakacinda’s, are still being prosecuted and convictions are being handed down.

“For the Nakacinda case, our concern stems from the fact that the government proceeded to prosecute a citizen based on a law that they acknowledge undermines Zambia’s democratic credentials,” the Chapter One Foundation said. The foundation expressed concern about “the deteriorating civil and political rights situation in Zambia. The delay in instituting structural reforms such as reviewing the Cyber Security and Cyber Crimes Act, for example, and its continued application to prosecute citizens that are critical of government, is of concern.”

Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Zambia ratified in 1984, those convicted of crimes must benefit from the imposition of lighter penalties that are adopted subsequent to the commission of the offense.

Human Rights Watch has consistently opposed criminal defamation provisions and prison sentences for nonviolent speech offenses. Human Rights Watch considers civil defamation provisions sufficient for the purpose of protecting people’s reputations, although they also can be abused.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that monitors compliance with the ICCPR, states in its general comment on freedom of expression that “imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty” for defamation. In addition, “all public figures … are legitimately subject to criticism.”

People in Zambia should be able to openly criticize the government without fear of reprisal. However, as Human Rights Watch has previously reported, ordinary people, journalists, human rights defenders, and political opposition members still face harassment for their perceived criticism of the authorities.

“Zambian authorities should stop harassing and prosecuting people to deprive them of their right to free speech and other fundamental liberties,” Nassah said. “Elected public officials in a rights-respecting democracy should have greater tolerance of criticism and scrutiny, and Zambians need to be able to exercise their basic rights without fear of reprisals.”