Dr Joseph Cooper, from the British Trust for Ornithology, shares recent research conducted alongside colleagues which saw the development of models. These models provide the foundation through which butterfly abundance could be integrated into an urban biodiversity assessment tool, providing species- and community-level statistics to non-specialists from the urban planning and design sector.

The prevailing view on new housing is it is built at the expense of nature. Most of us now live in urban areas and, having gone through the COVID pandemic, understand the value of interacting with wildlife close to our homes. Yet, the more we build, the more we entomb residents into spaces where there is less access to nature.

How can we make housing developments more wildlife-friendly?

Non-specialists from the planning and design sector cannot be expected to know how to make developments wildlife friendly. If we want to build human-wildlife interactions into our living spaces, we need it to feature in the planning tools they use. To establish such a measure, we first need an understanding of the relationships species have with the urban environment.

England was our chosen study location, as the UK government has pledged to increase the housing stock whilst also introducing a legal requirement to improve biodiversity. New construction projects are judged on biodiversity targets through a digital tool called the Biodiversity Metric. There is growing recognition the tool undervalues gardens, urban shrubbery, and allotments, meaning developers have little motivation to design housing developments with spaces for regular human-wildlife interactions. Instead, they are encouraged to compensate for any biodiversity losses ‘off-site’.

A focus on butterflies

We focused on butterflies because:

- they can be sensitive to small changes in habitat

- are commonly seen in urban settings

- and can reflect the responses of other insects.

Counts of flying adults from 160 urban sites were obtained from the Wider Countryside Butterfly Survey (WCBS), a national citizen science recording scheme. The area around each survey route was broken down into the percentage each was covered by different types of land, such as housing, roads, and private gardens. A combination of Ordnance Survey mapping and satellite imagery was used to distinguish these different features.

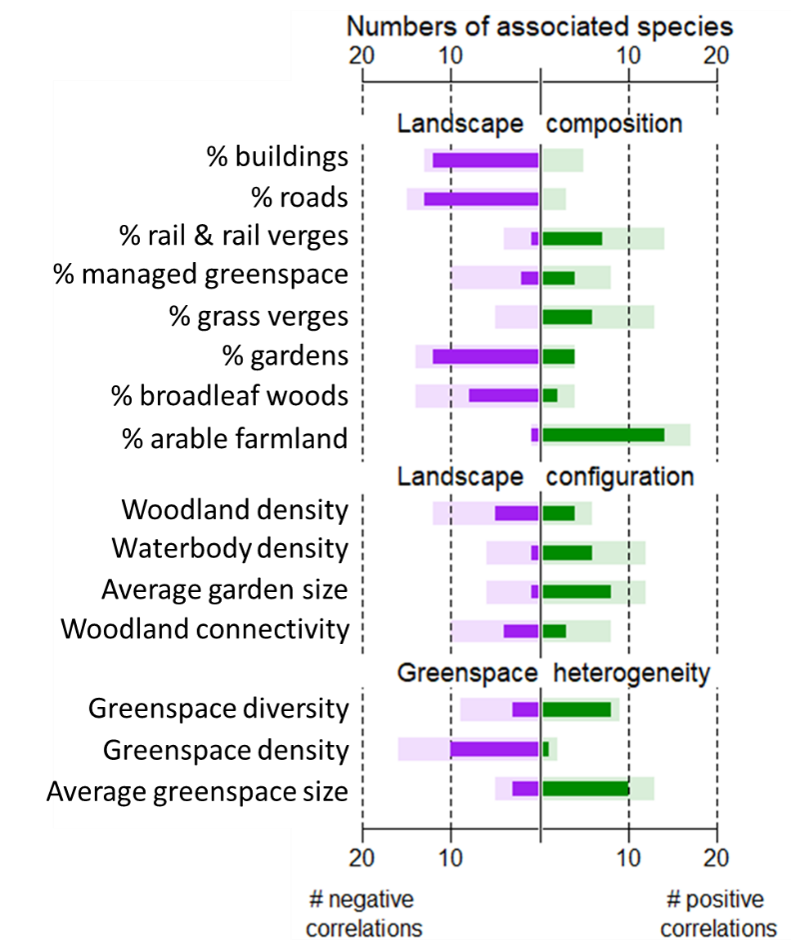

We also assessed the connectivity and diversity of greenspaces and woodland and reviewed the quantity of broader habitats in the wider landscape, such waterbodies and farmland. This information was analysed in statistical models, allowing us to quantify how 18 butterfly species responded to 32 different measures of urban environments.

Our results

The results could be greatly informative for wildlife-friendly development design (see figure). Most butterfly species had positive responses to greenspaces where management is less frequent, such as grass verges and railway embankments. These habitats were correlated with greater sightings of butterflies compared to the equivalent area of greenspace where the vegetation is more regularly cut.

One additional benefit of our approach is because we establish species-specific relationships, we can highlight those which behave in contrast to the wider butterfly community. For example, Holly Blue Celastrina argiolus, and Red Admiral Vanessa atalanta were found to thrive in built-up areas where there are number of smaller, private gardens.

How our findings can be implemented

Our ambition is to package the created butterfly models, alongside those from other taxa, into a new urban- environment biodiversity prediction tool. Practitioners should receive digestible species information, based upon the biophysical nature of their development site, and the configuration of habitats in their plan.

When used over multiple plans, the user should see which supports the most species or has the highest likelihood of encounters with particular species or species groups. This could help to arm developers in creating biodiverse spaces for us to live and reduce their use of off-site offsetting schemes.

It is true that many species will struggle to live close to human habitation. However, when building new housing is unavoidable, the next best solution is to design developments with regular wildlife interactions in mind. If we can reduce the barriers between residents and the natural world, we build more awareness and engagement on wider environmental issues. Perhaps then, the discourse around new housing can shift from “what have we lost?” to “look what we saw today!”.

We would like to thank all the WCBS volunteers, as without their efforts, this analysis would not have been possible.

Read the full article “Using butterfly survey data to model habitat associations in urban developments” in Journal of Applied Ecology