Coban is Grab’s real-time data streaming platform team. As a platform team, we thrive on providing our internal users from all verticals with self-served data-streaming resources, such as Kafka topics, Flink and Change Data Capture (CDC) pipelines, various kinds of Kafka-Connect connectors, as well as Apache Zeppelin notebooks, so that they can effortlessly leverage real-time data to build intelligent applications and services.

In this article, we present our journey from pure Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) towards a more sophisticated control plane that has revolutionised the way data streaming resources are self-served at Grab. This change also leads to improved scalability, stability, security, and user adoption of our data streaming platform.

Problem statement

In the early ages of public cloud, it was a common practice to create virtual resources by clicking through the web console of a cloud provider, which is sometimes referred to as ClickOps.

ClickOps has many downsides, such as:

- Inability to review, track, and audit changes to the infrastructure.

- Inability to massively scale the infrastructure operations.

- Inconsistencies between environments, e.g. staging and production.

- Inability to quickly recover from a disaster by re-creating the infrastructure at a different location.

That said, ClickOps has one tremendous advantage; it makes creating resources using a graphical User Interface (UI) fairly easy for anyone like Infrastructure Engineers, Software Engineers, Data Engineers etc. This also leads to a high iteration speed towards innovation in general.

IaC resolved many of the limitations of ClickOps, such as:

- Changes are committed to a Version Control System (VCS) like Git: They can be reviewed by peers before being merged. The full history of all changes is available for investigating issues and for audit.

- The infrastructure operations scale better: Code for similar pieces of infrastructure can be modularised. Changes can be rolled out automatically by Continuous Integration (CI) pipelines in the VCS system, when a change is merged to the main branch.

- The same code can be used to deploy the staging and production environments consistently.

- The infrastructure can be re-created anytime from its source code, in case of a disaster.

However, IaC unwittingly posed a new entry barrier too, requiring the learning of new tools like Ansible, Puppet, Chef, Terraform, etc.

Some organisations set up dedicated Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) teams to centrally manage, operate, and support those tools and the infrastructure as a whole, but that soon created the potential of new bottlenecks in the path to innovation.

On the other hand, others let engineering teams manage their own infrastructure, and Grab adopted that same approach. We use Terraform to manage infrastructure, and all teams are expected to have select engineers who have received Terraform training and have a clear understanding of it.

In this context, Coban’s platform initially started as a handful of Git repositories where users had to submit their Merge Requests (MR) of Terraform code to create their data streaming resources. Once reviewed by a Coban engineer, those Terraform changes would be applied by a CI pipeline running Atlantis.

While this was a meaningful first step towards self-service and platformisation of Coban’s offering within Grab, it had several significant downsides:

- Stability: Due to the lack of control on the Terraform changes, the CI pipeline was prone to human errors and frequent failures. For example, users would initiate a new Terraform project by duplicating an existing one, but then would forget to change the location of the remote Terraform state, leading to the in-place replacement of an existing resource.

- Scalability: The Coban team needed to review all MRs and provide ad hoc support whenever the pipeline failed.

- Security: In the absence of Identity and Access Management (IAM), MRs could potentially contain changes pertaining to other teams’ resources, or even changes to Coban’s core infrastructure, with code review as the only guardrail.

- Limited user growth: We could only acquire users who were well-versed in Terraform.

It soon became clear that we needed to build a layer of abstraction between our users and the Terraform code, to increase the level of control and lower the entry barrier to our platform, while still retaining all of the benefits of IaC under the hood.

Solution

We designed and built an in-house three-tier control plane made of:

- Coban UI, a front-end web interface, providing our users with a seamless ClickOps experience.

- Heimdall, the Go back-end of the web interface, transforming ClickOps into IaC.

- Khone, the storage and provisioner layer, a Git repository storing Terraform code and metadata of all resources as well as the CI pipelines to plan and apply the changes.

In the next sections, we will deep dive in those three components.

Although we designed the user journey to start from the Coban UI, our users can still opt to communicate with Heimdall and with Khone directly, e.g. for batch changes, or just because many engineers love Git and we want to encourage broad adoption. To make sure that data is eventually consistent across the three systems, we made Khone the only persistent storage layer. Heimdall regularly fetches data from Khone, caches it, and presents it to the Coban UI upon each query.

We also continued using Terraform for all resources, instead of mixing various declarative infrastructure approaches (e.g. Kubernetes Custom Resource Definition, Helm charts), for the sake of consistency of the logic in Khone’s CI pipelines.

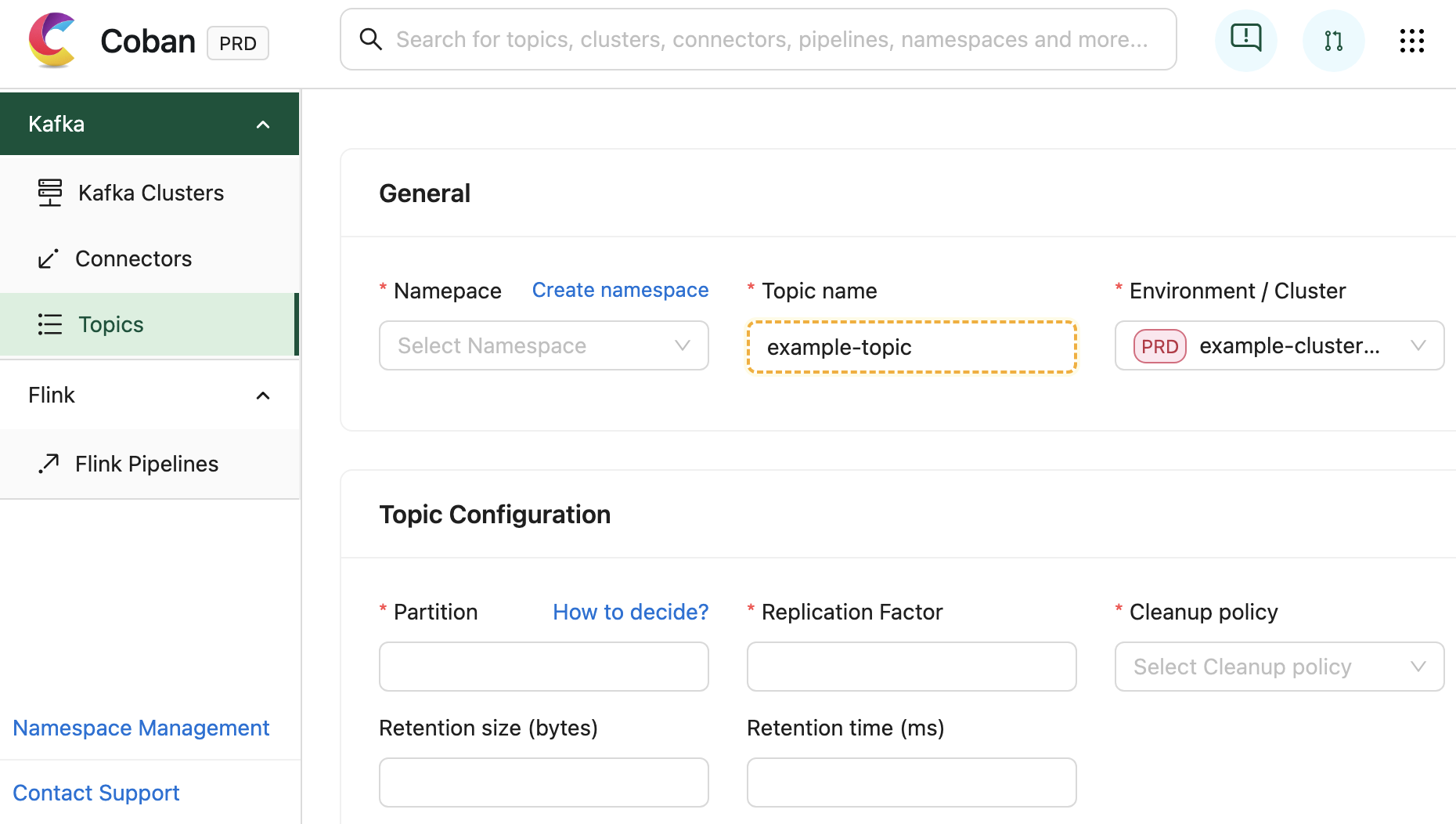

Coban UI

The Coban UI is a React Single Page Application (React SPA) designed by our partner team Chroma, a dedicated team of front-end engineers who thrive on building legendary UIs and reusable components for platform teams at Grab.

It serves as a comprehensive self-service portal, enabling users to effortlessly create data streaming resources by filling out web forms with just a few clicks.

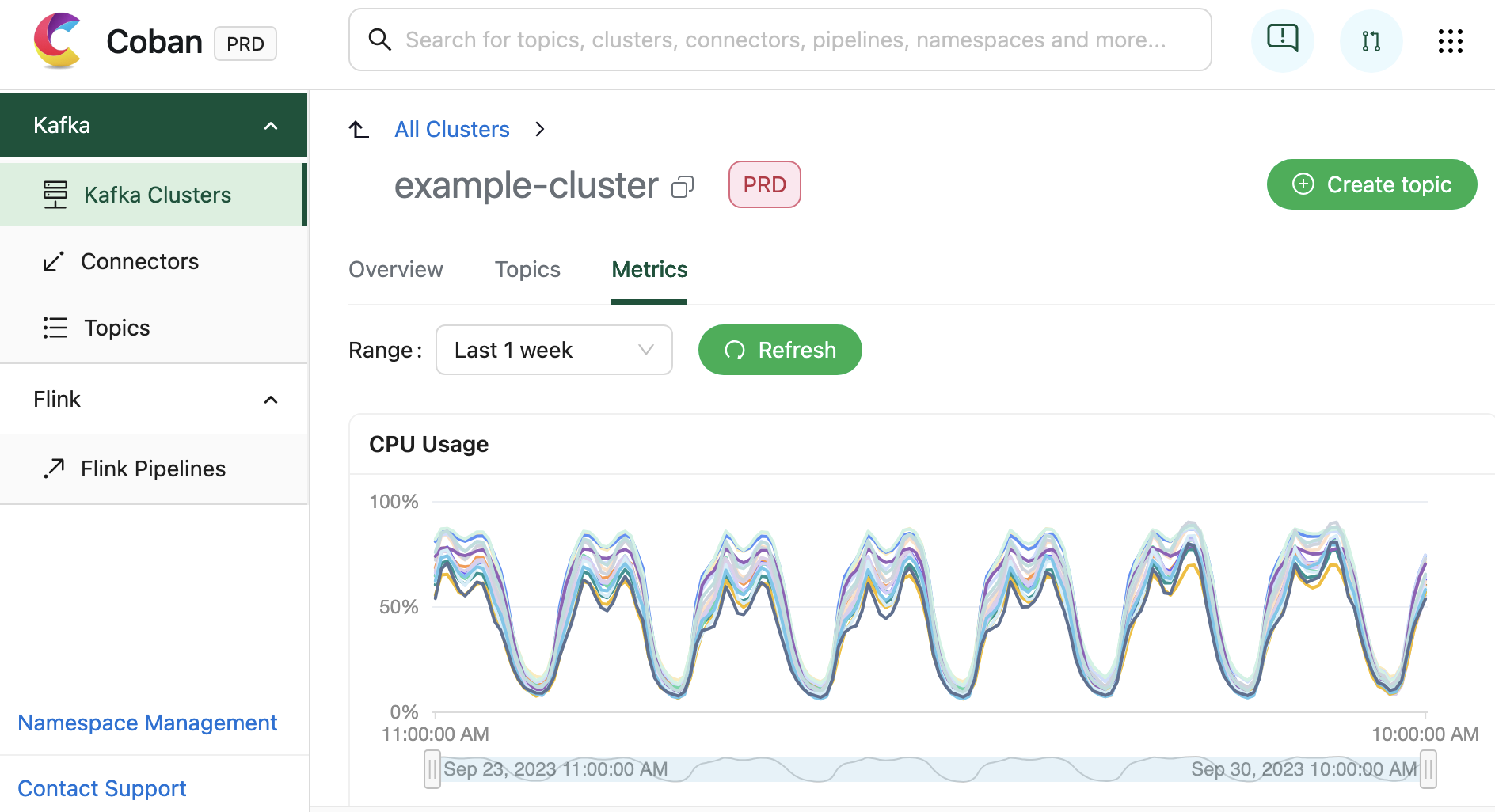

In addition to facilitating resource creation and configuration, the Coban UI is seamlessly integrated with multiple monitoring systems. This integration allows for real-time monitoring of critical metrics and health status for Coban infrastructure components, including Kafka clusters, Kafka topic bytes in/out rates, and more. Under the hood, all this information is exposed by Heimdall APIs.

In terms of infrastructure, the Coban UI is hosted in AWS S3 website hosting. All dynamic content is generated by querying the APIs of the back-end: Heimdall.

Heimdall

Heimdall is the Go back-end of the Coban UI. It serves a collection of APIs for:

- Managing the data streaming resources of the Coban platform with Create, Read, Update and Delete (CRUD) operations, treating the Coban UI as a first-class citizen.

- Exposing the metadata of all Coban resources, so that they can be used by other platforms or searched in the Coban UI.

All operations are authenticated and authorised. Read more about Heimdall’s access control in Migrating from Role to Attribute-based Access Control.

In the next sections, we are going to dive deeper into these two features.

Managing the data streaming resources

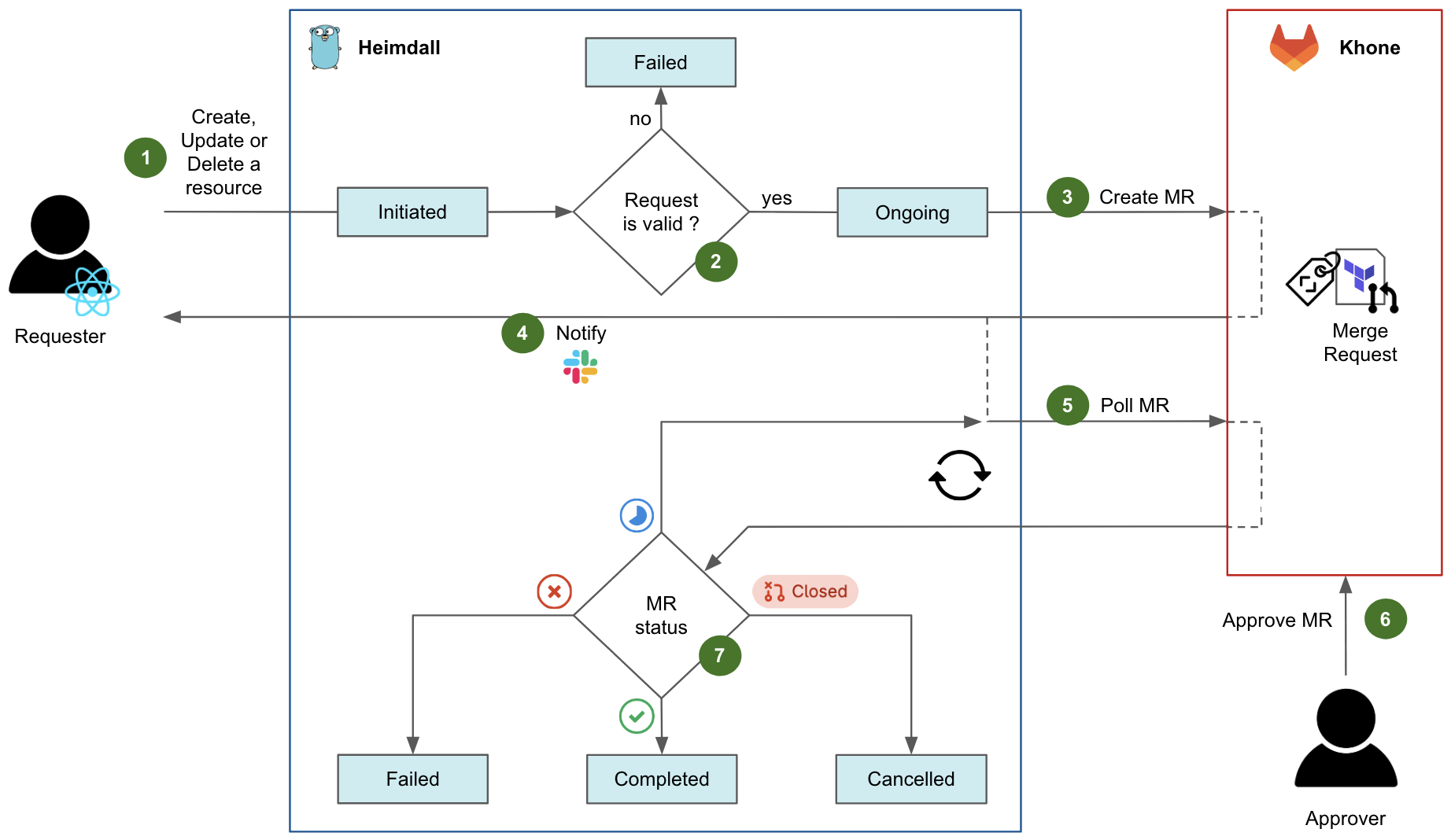

First and foremost, Heimdall enables our users to self-manage their data streaming resources. It primarily relies on Khone as its storage and provisioner layer for actual resource management via Git CI pipelines. Therefore, we designed Heimdall’s resource management workflow to leverage the underlying Git flow.

Fig. 4 shows the diagram flow of a typical request in Heimdall to create, update, or delete a resource.

- An authenticated user initiates a request, either by navigating in the Coban UI or by calling the Heimdall API directly. At this stage, the request state is

Initiatedon Heimdall. - Heimdall validates the request against multiple validation rules. For example, if an ongoing change request exists for the same resource, the request fails. If all tests succeed, the request state moves to

Ongoing. - Heimdall then creates an MR in Khone, which contains the Terraform files describing the desired state of the resource, as well as an in-house metadata file describing the key attributes of both resource and requester.

- After the MR has been created successfully, Heimdall notifies the requester via Slack and shares the MR URL.

- After that, Heimdall starts polling the status of the MR in a loop.

- For changes pertaining to production resources, an approver who is code owner in the repository of the resource has to approve the MR. Typically, the approver is an immediate teammate of the requester. Indeed, as a platform team, we empower our users to manage their own resources in a self-service fashion. Ultimately, the requester would merge the MR to trigger the CI pipeline applying the actual Terraform changes. Note that for staging resources, this entire step 6 is automatically performed by Heimdall.

- Depending on the MR status and the status of its CI pipeline in Khone, the final state of the request can be:

Failedif the CI pipeline has failed in Khone.Completedif the CI pipeline has succeeded in Khone.Cancelledif the MR was closed in Khone.

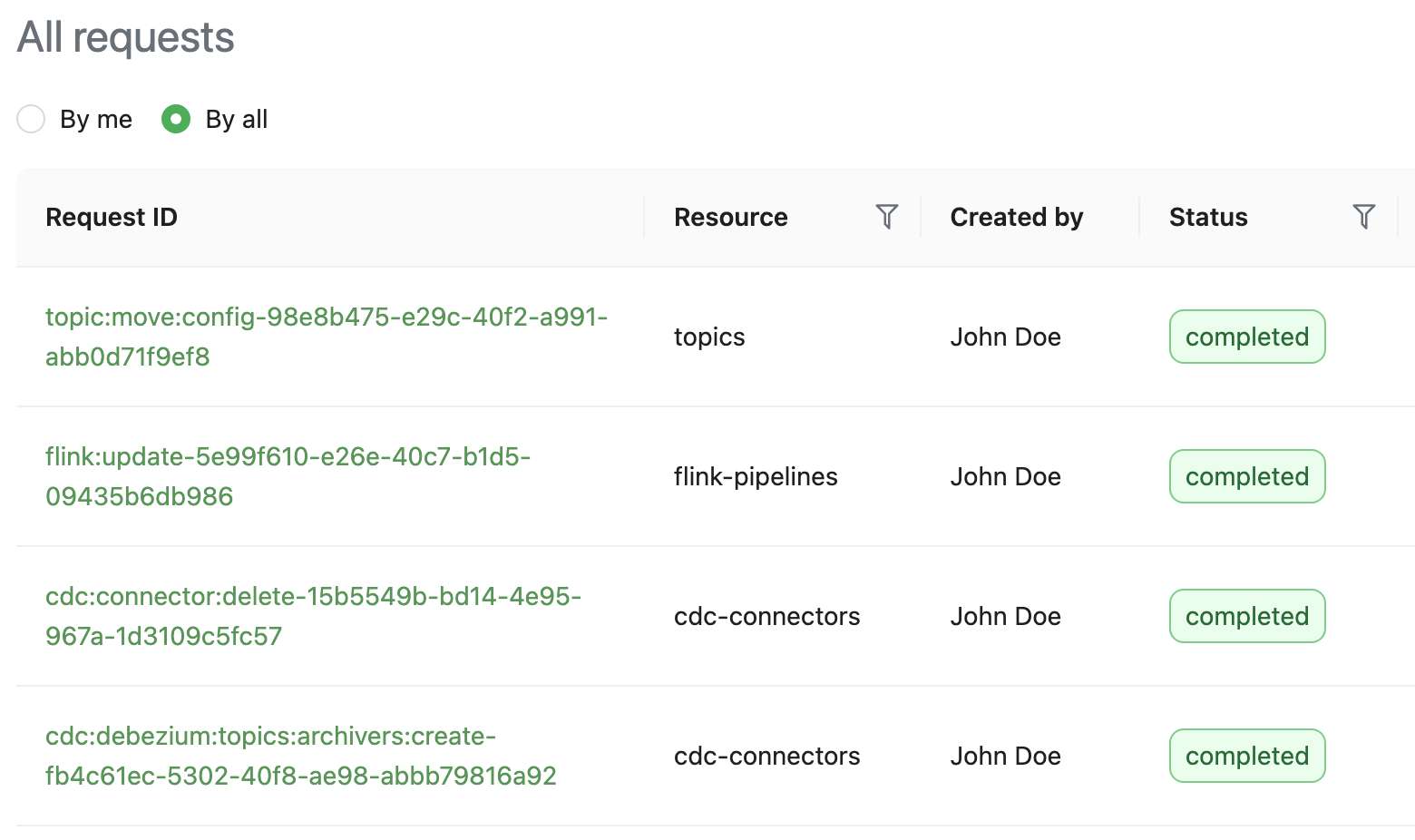

Heimdall exposes APIs to let users track the status of their requests. In the Coban UI, a page queries those APIs to elegantly display the requests.

Exposing the metadata

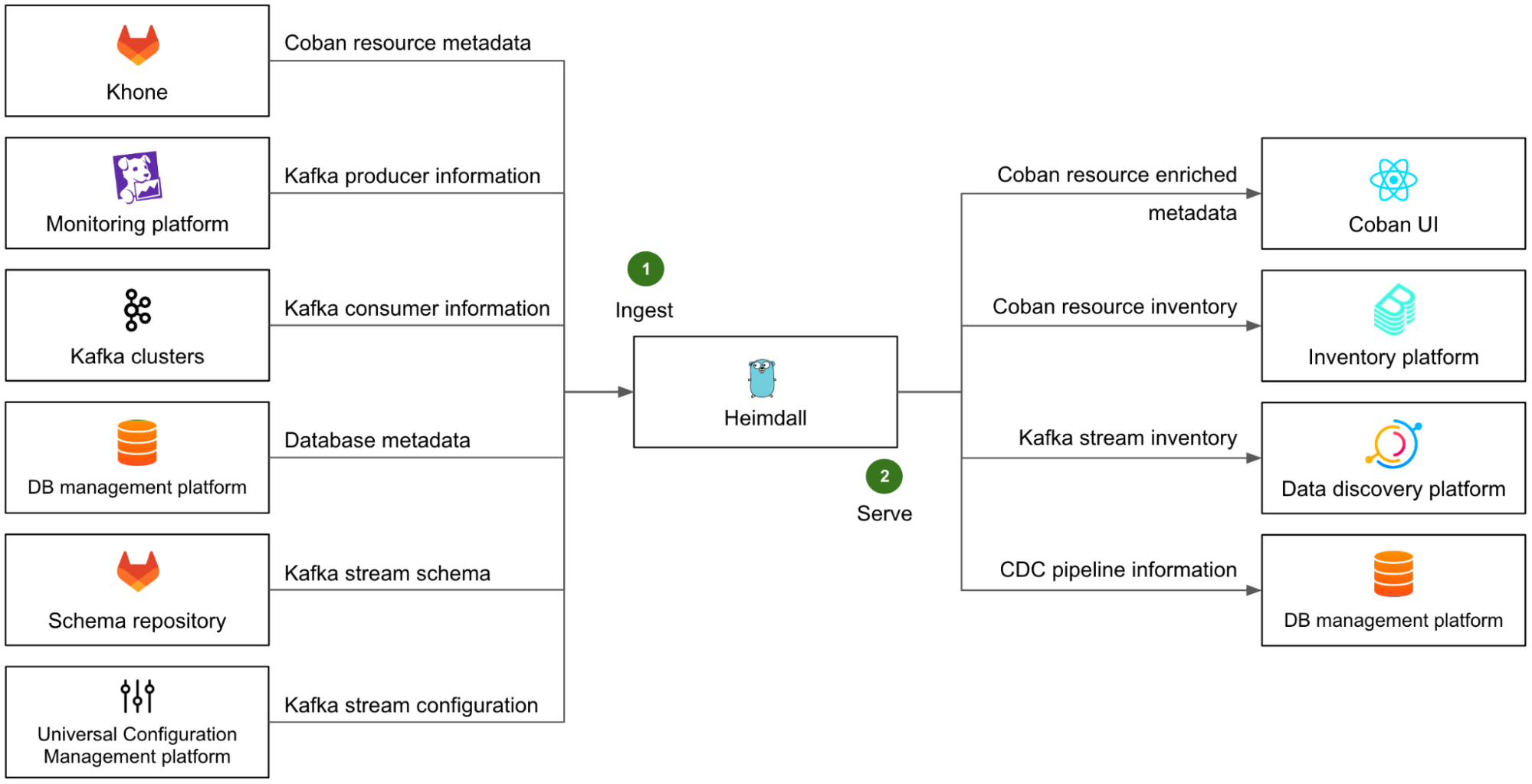

Apart from managing the data streaming resources, Heimdall also centralises and exposes the metadata pertaining to those resources so other Grab systems can fetch and use it. They can make various queries, for example, listing the producers and consumers of a given Kafka topic, or determining if a database (DB) is the data source for any CDC pipeline.

To make this happen, Heimdall not only retains the metadata of all of the resources that it creates, but also regularly ingests additional information from a variety of upstream systems and platforms, to enrich and make this metadata comprehensive.

On the left side of Fig. 6, we illustrate Heimdall’s ingestion mechanism with several examples (step 1):

- The metadata of all Coban resources is ingested from Khone. This means the metadata of the resources that were created directly in Khone is also available in Heimdall.

- The list of Kafka producers is retrieved from our monitoring platform, where most of them emit metrics.

- The list of Kafka consumers is retrieved directly from the respective Kafka clusters, by listing the consumer groups and respective Client IDs of each partition.

- The metadata of all DBs, that are used as a data source for CDC pipelines, is fetched from Grab’s internal DB management platform.

- The Kafka stream schemas are retrieved from the Coban schema repository.

- The Kafka stream configuration of each stream is retrieved from Grab Universal Configuration Management platform.

With all of this ingested data, Heimdall can provide comprehensive and accurate information about all data streaming resources to any other Grab platforms via a set of dedicated APIs.

The right side of Fig. 6 shows some examples (step 2) of Heimdall’s serving mechanism:

- As a downstream of Heimdall, the Coban UI enables our direct users to conveniently browse their data streaming resources and access their attributes.

- The entire resource inventory is ingested into the broader Grab inventory platform, based on backstage.io.

- The Kafka streams are ingested into Grab’s internal data discovery platform, based on DataHub, where users can discover and trace the lineage of any piece of data.

- The CDC connectors pertaining to DBs are ingested by Grab internal DB management platform, so that they are made visible in that platform when users are browsing their DBs.

Note that the downstream platforms that ingest data from Heimdall each expose a particular view of the Coban inventory that serves their purpose, but the Coban platform remains the only source of truth for any data streaming resource at Grab.

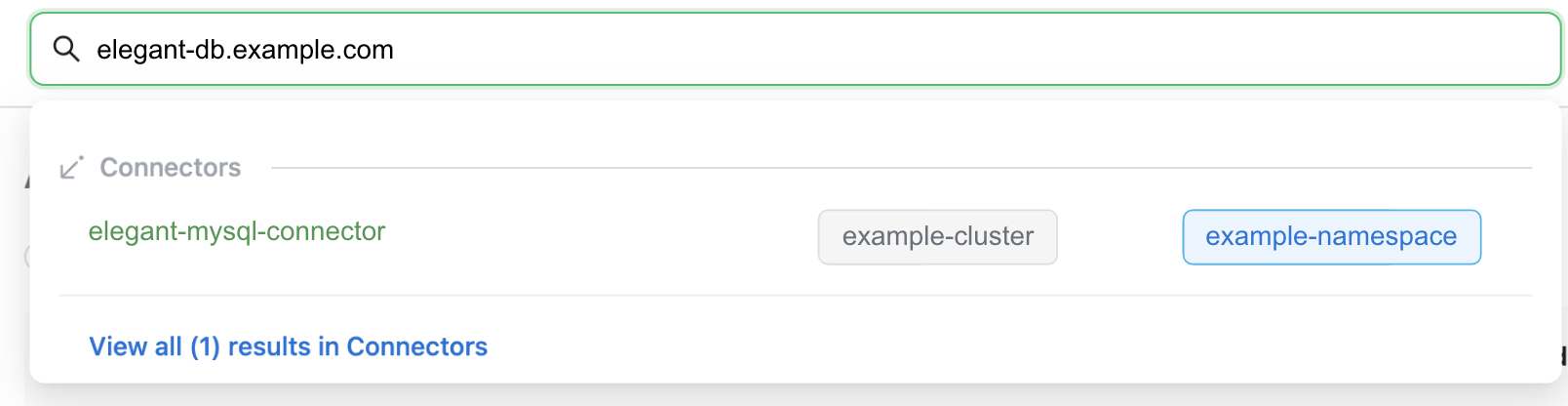

Lastly, Heimdall leverages an internal MySQL DB to support quick data query and exploration. The corresponding API is called by the Coban UI to let our users conveniently search globally among all resources’ attributes.

Khone

Khone is the persistent storage layer of our platform, as well as the executor for actual resource creation, changes, and deletion. Under the hood, it is actually a GitLab repository of Terraform code in typical GitOps fashion, with CI pipelines to plan and apply the Terraform changes automatically. In addition, it also stores a metadata file for each resource.

Compared to letting the platform create the infrastructure directly and keep track of the desired state in its own way, relying on a standard IaC tool like Terraform for the actual changes to the infrastructure presents two major advantages:

- The Terraform code can directly be used for disaster recovery. In case of a disaster, any entitled Cobaner with a local copy of the main branch of the Khone repository is able to recreate all our platform resources directly from their machine. There is no need to rebuild the entire platform’s control plane, thus reducing our Recovery Time Objective (RTO).

- Minimal effort required to follow the API changes of our infrastructure ecosystem (AWS, Kubernetes, Kafka, etc.). When such a change happens, all we need to do is to update the corresponding Terraform provider.

If you’d like to read more about Khone, check out Securing GitOps pipelines. In this section, we will only focus on Khone’s features that are relevant from the platform perspective.

Lightweight Terraform

In Khone, each resource is stored as a Terraform definition. There are two major differences from a normal Terraform project:

- No Terraform environment, such as the required Terraform providers and the location of the remote Terraform state file. They are automatically generated by the CI pipeline via a simple wrapper.

- Only vetted Khone Terraform modules can be used. This is controlled and enforced by the CI pipeline via code inspection. There is one such Terraform module for each kind of supported resource of our platform (e.g. Kafka topic, Flink pipeline, Kafka Connect mirror source connector etc.). Furthermore, those in-house Terraform modules are designed to automatically derive their key variables (e.g. resource name, cluster name, environment) from the relative path of the parent Terraform project in the Khone repository.

Those characteristics are designed to limit the risk and blast radius of human errors. They also make sure that all resources created in Khone are supported by our platform, so that they can also be discovered and managed in Heimdall and the Coban UI. Lastly, by generating the Terraform environment on the fly, we can destroy resources simply by deleting the directory of the project in the code base – this would not be possible otherwise.

Resource metadata

All resource metadata is stored in a YAML file that is present in the Terraform directory of each resource in the Khone repository. This is mainly used for ownership and cost attribution.

With this metadata, we can:

- Better communicate with our users whenever their resources are impacted by an incident or an upcoming maintenance operation.

- Help teams understand the costs of their usage of our platform, a significant step towards cost efficiency.

There are two different ways resource metadata can be created:

- Automatically through Heimdall: The YAML metadata file is automatically generated by Heimdall.

- Through Khone by a human user: The user needs to prepare the YAML metadata file and include it in the MR. This file is then verified by the CI pipeline.

Outcome

The initial version of the three-tier Coban platform, as described in this article, was internally released in March 2022, supporting only Kafka topic management at the time. Since then, we have added support for Flink pipelines, four kinds of Kafka Connect connectors, CDC pipelines, and more recently, Apache Zeppelin notebooks. At the time of writing, the Coban platform manages about 5000 data streaming resources, all described as IaC under the hood.

Our platform also exposes enriched metadata that includes the full data lineage from Kafka producers to Kafka consumers, as well as ownership information, and cost attribution.

With that, our monthly active users have almost quadrupled, truly moving the needle towards democratising the usage of real-time data within all Grab verticals.

In spite of that user growth, the end-to-end workflow success rate for self-served resource creation, change or deletion, remained well above 90% in the first half of 2023, while the Heimdall API uptime was above 99.95%.

Challenges faced

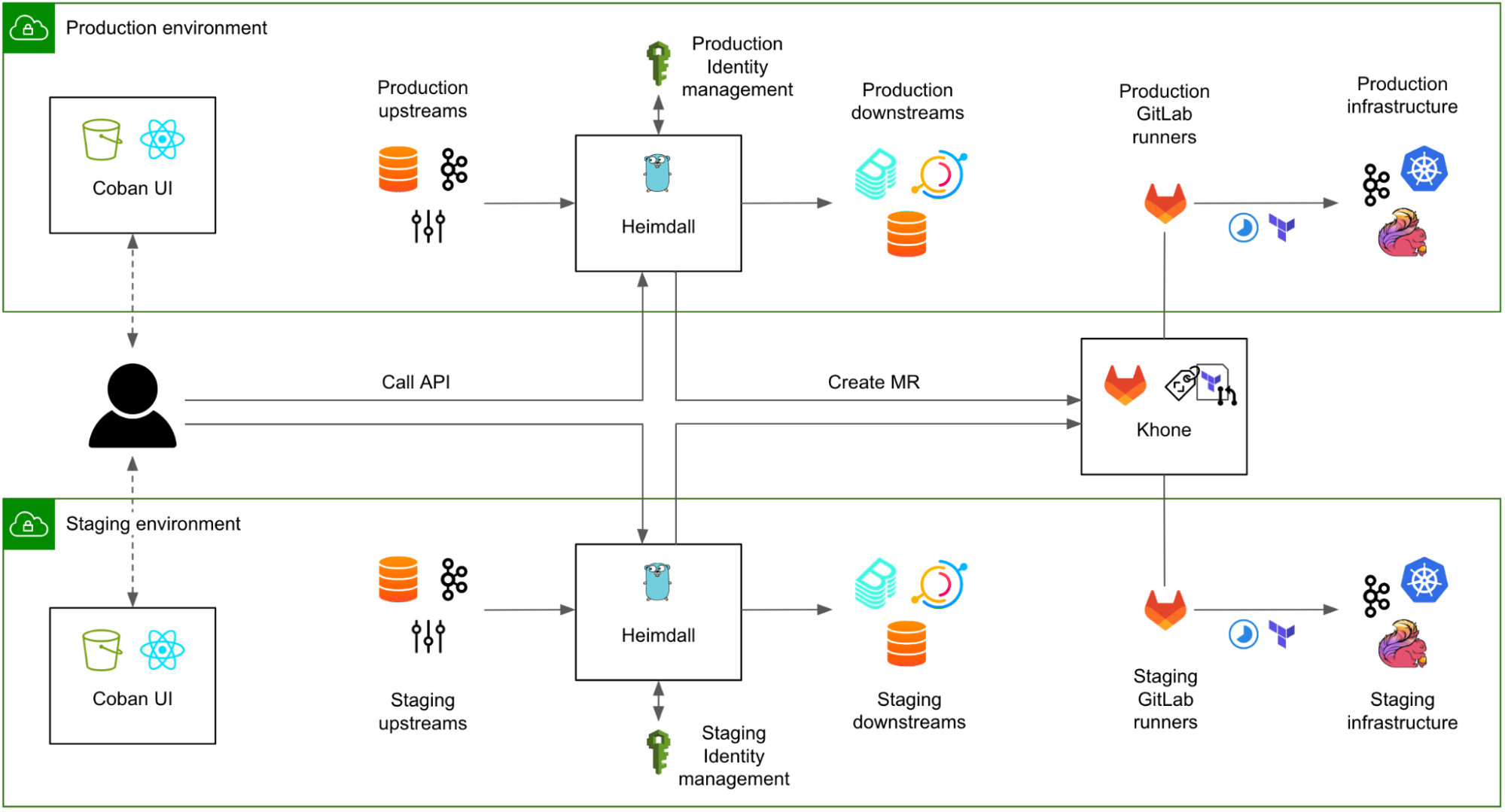

A common challenge for platform teams resides in the misalignment between the Service Level Objective (SLO) of the platform, and the various environments (e.g. staging, production) of the managed resources and upstream/downstream systems and platforms.

Indeed, the platform aims to guarantee the same level of service, regardless of whether it is used to create resources in the staging or the production environment. From the platform team’s perspective, the platform as a whole is considered production-grade, as soon as it serves actual users.

A naive approach to address this challenge is to let the production version of the platform manage all resources regardless of their respective environments. However, doing so does not permit a hermetic segregation of the staging and production environments across the organisation, which is a good security practice, and often a requirement for compliance. For example, the production version of the platform would have to connect to upstream systems in the staging environment, e.g. staging Kafka clusters to collect their consumer groups, in the case of Heimdall. Conversely, the staging version of certain downstreams would have to connect to the production version of Heimdall, to fetch the metadata of relevant staging resources.

The alternative approach, generally adopted across Grab, is to instantiate all platforms in each environment (staging and production), while still considering both instances as production-grade and guaranteeing tight SLOs in both environments.

In Fig. 8, both instances of Heimdall have equivalent SLOs. The caveat is that all upstream systems and platforms must also guarantee a strict SLO in both environments. This obviously comes with a cost, for example, tighter maintenance windows for the operations pertaining to the Kafka clusters in the staging environment.

A strong “platform” culture is required for platform teams to fully understand that their instance residing in the staging environment is not their own staging environment and should not be used for testing new features.

What’s next?

Currently, users creating, updating, or deleting production resources in the Coban UI (or directly by calling Heimdall API) receive the URL of the generated GitLab MR in a Slack message. From there, they must get the MR approved by a code owner, typically another team member, and finally merge the MR, for the requested change to be actually implemented by the CI pipeline.

Although this was a fairly easy way to implement a maker/checker process that was immediately compliant with our regulatory requirements for any changes in production, the user experience is not optimal. In the near future, we plan to bring the approval mechanism into Heimdall and the Coban UI, while still providing our more advanced users with the option to directly create, approve, and merge MRs in GitLab. In the longer run, we would also like to enhance the Coban UI with the output of the Khone CI jobs that include the Terraform plan and apply results.

There is another aspect of the platform that we want to improve. As Heimdall regularly polls the upstream platforms to collect their metadata, this introduces a latency between a change in one of those platforms and its reflection in the Coban platform, which can hinder the user experience. To refresh resource metadata in Heimdall in near real time, we plan to leverage an existing Grab-wide event stream, where most of the configuration and code changes at Grab are produced as events. Heimdall will soon be able to consume those events and update the metadata of the affected resources immediately, without waiting for the next periodic refresh.

Grab is the leading superapp platform in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter to consumers. More than just a ride-hailing and food delivery app, Grab offers a wide range of on-demand services in the region, including mobility, food, package and grocery delivery services, mobile payments, and financial services across 428 cities in eight countries.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!