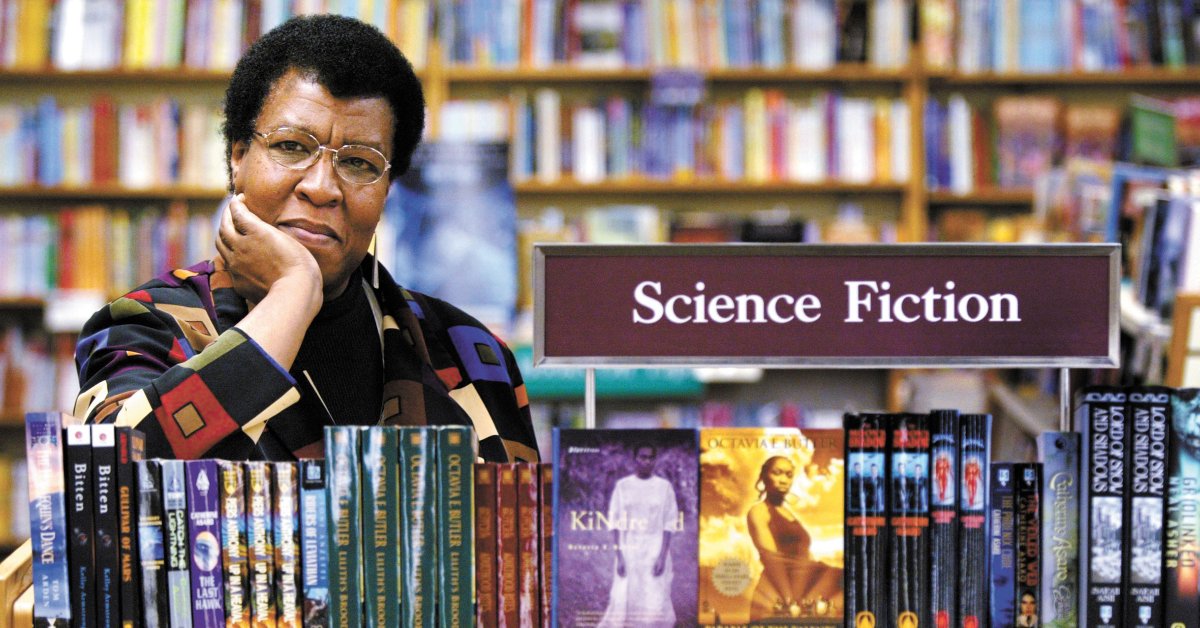

By the time Octavia Estelle Butler published Kindred in 1979, she had begun to solidify her place in the science-fiction genre—no small feat for a Black woman in a world dominated by white men and their stories of colonizing planets and alien invasions. She had achieved moderate success with her first three books, Patternmaster, Mind of My Mind, and Survivor—a series set in a far future world of telepathic humans and highlighting the power dynamics between masters and the enslaved. Kindred, her fourth novel, was a departure, a story in which a contemporary Black woman in an interracial marriage is summoned back in time to Maryland in 1815.

Back in 2001, I was an aspiring writer attending the Clarion West Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Workshop in Seattle. Butler had attended a Clarion workshop 30 years prior as a student, but now she was back to teach eager pupils like me. I, like many others, became a fan long before the T-shirts and the Butler-tried-to-tell-us social media posts. Having grown up with a healthy diet of science-fiction movies and TV shows as a child of the ‘80s, reading about Black girls and women in the future was validating. While Butler’s novels are certainly cautionary tales, she was not a fortuneteller. She was a lover of science, an inquisitive writer, and a keen observer of society. Butler simply paid close attention to human behavior.

The idea that human beings are hierarchical permeates Butler’s work, and it’s what she tried to explain to me during an in-depth conversation at a party in Seattle. I was a young, idealistic Pan-Africanist and feminist who believed that Black liberation could be achieved by dismantling patriarchy and white supremacy. Butler believed that humans crave dominance. Eradicate one group and another will take its place. This is also true for Black people and other marginalized groups, she told me. It was a hard lesson to digest, and it was an idea that she instilled in her teaching: We are a flawed species and in order to convey that in our stories, we had to study our surroundings and say something big about the world with close details. “Make people touch and taste and know,” she wrote in one of her journals. “Make people feel, feel, feel!”

Throughout the ‘70s, on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement, Butler wrote short stories where she imagined dystopian futures filled with power-hungry shapeshifters, vulnerable empaths, and parasitic aliens. Then, she turned her attention to the visceral past and placed a Black woman at the center of her own story. Kindred is where Butler’s lessons on writing with closely felt details and nuanced physicality are on full display. Time-travel stories had been a staple of science-fiction for decades, but we didn’t—and still don’t—often associate the genre with Black women’s bodies and slave narratives.

Slavery was the terrain of historical fiction, and the late ‘70s were a pinnacle for those stories. Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family was published in August 1976 and the miniseries premiered in January 1977. Americans confronted the horrors of slavery on their televisions in the form of young LeVar Burton’s defiant Kunta Kente. This was historical fiction at its best.

Kindred was something different. In it, Butler merged history with the present, and a contemporary Black woman’s body became a time machine—a device to fold time back on itself. Butler presented slavery as a haunting science that created monstrosities, much like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Dana Franklin, Kindred’s protagonist, must survive antebellum plantation life from the perspective of 1976’s racial politics. Here, the future is prologue. Dana stands at the junction between the monstrous past and the alien world of post-racial America—a perpetually elusive dream since the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. In Kindred, horror and science-fiction intersect. Yet, Butler described the work as a sort of “grim fantasy.” And now, 43 years after its publication, nearly 46 years after the premier of Roots, 16 years after Butler’s death, and in middle of yet another violent “racial reckoning” in America, that fantasy gets a TV series.

Read More: FX’s Kindred Is a Solid, Long Overdue Adaptation of Octavia E. Butler’s Masterpiece

I wonder what Butler would make of this, of her story about a Black woman traveling back in time to contend with not only the past and her ancestry but with her body reaching a new audience of millions of viewers in 2022. Today we know that intergenerational trauma, particularly for the descendants of slavery (both enslaved and enslavers), is a biological and psychological fact. We also know that a variety of ailments affect Black women at disproportionate rates. And somehow, Butler already knew all this when she wrote Kindred. She correctly observed that pain, torture, and dismemberment are horrors that leave scars on the psyche—scars that are inherited by future generations. She knew that only by intertwining the past with the present could we begin to connect the cellular dots. Butler’s much-praised foresight is not only evident in her Parable series, where a demagogue president, Christopher Donner, wants to “make America great again.” It plays a central role in Kindred, where she shows us that the traumas of the past can live in the body and impact the present and the future.

Even as stories of America’s horrific past are pulled from libraries and schools across the country, history continues to live on in our cells. Honest storytelling sheds light on generational trauma, and if we heed its warnings, it can be medicine and possibly an inoculation. As the descendants of enslavers and the enslaved, we are reminded that we can be both monster and alien in our cruelty towards each other and in our ability to adapt and change.

“God is change,” writes Lauren Oya Olamina, the teenage protagonist of Butler’s Parable series, as she forms Earthseed, a neo-religion and fringe community attempting to remake humanity amid societal collapse. In Kindred, the dystopia is slavery; change is the passage of time as a nation moves from war and emancipation to reconciliation; and god is Dana, a Black woman who stands at the precipice of it all—enslavement and freedom, biology and physics, science and memory.

More Must-Reads From TIME