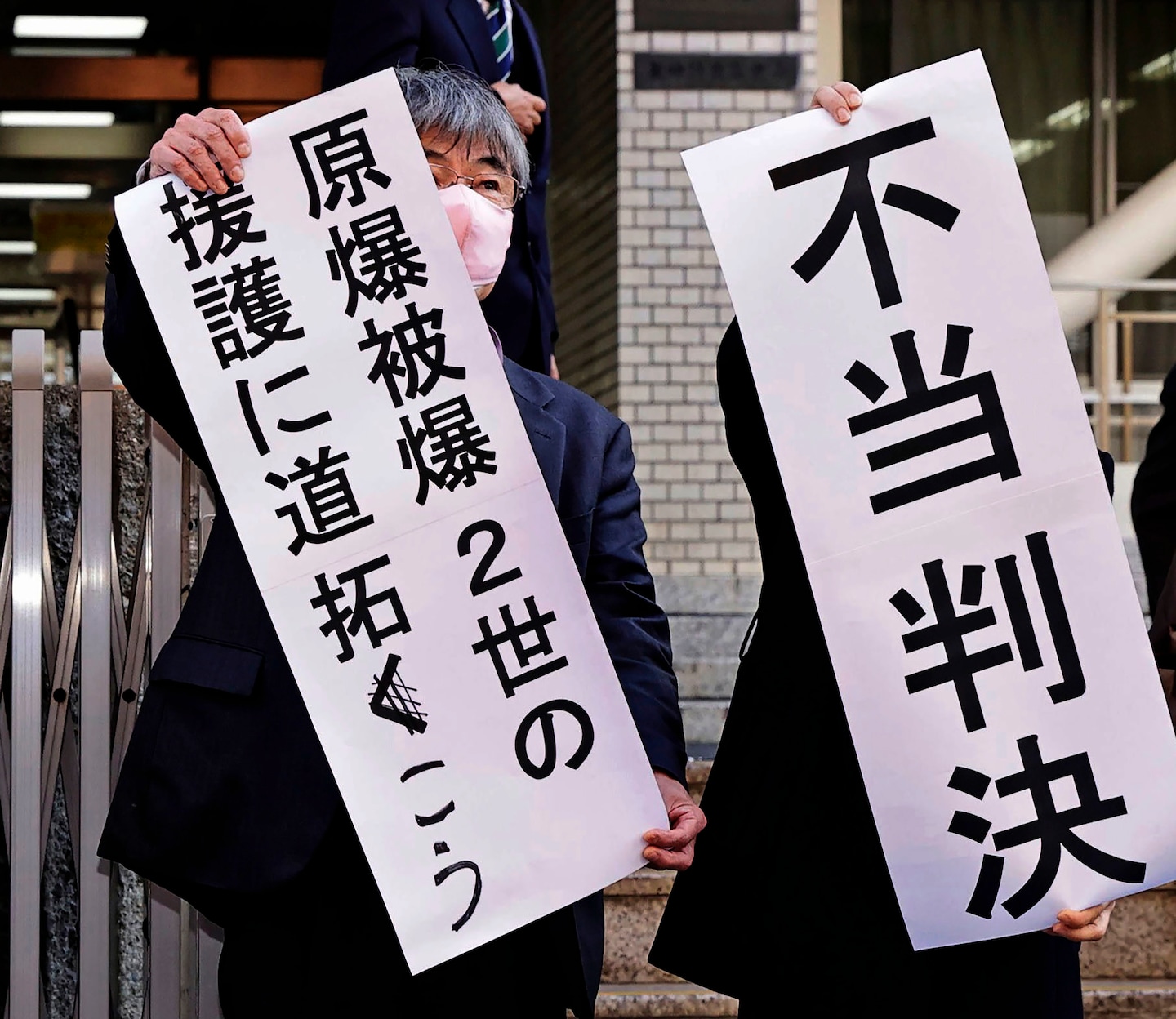

The Nagasaki District Court said Monday that a possible hereditary radiation effect cannot be denied, but there is no established scientific consensus and that the government’s exclusion of the plaintiffs from medical support is not unconstitutional.

The court, however, said it is up to the government to decide whether to expand financial support to include second-generation survivors.

The government has maintained that there is no scientific evidence showing hereditary impact of parents’ radiation exposure to their children.

The plaintiffs, aged in their 50s to 70s, sought 100,000 yen ($730) each from the government in damages, saying their exclusion violated constitutional equality. A similar lawsuit is pending at the Hiroshima district court, where a ruling is expected early next year.

The United States dropped the world’s first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, destroying the city and killing 140,000 people. It dropped a second bomb three days later on Nagasaki, killing another 70,000. Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, ending World War II and its nearly half-century of aggression in Asia.

Many survivors of the bombings have lasting injuries and illnesses resulting from the explosions and radiation exposure and have faced discrimination in Japan.

Their children, known as “hibaku nisei,” or second-generation survivors of atomic bombing, say they have constantly worried about possible hereditary effects of radiation from their parents’ exposures, and many have developed various forms of cancer and other health problems. They estimate their numbers at 300,000 to 500,000.

Currently, only the survivors and those who had prenatal exposures who were certified can receive government medical support for their radiation illnesses and cancer checkups. The government started providing free medical checks for their children in 1979 but cancer examinations are not included.

In his statement at the final court session in July, Noboru Sakiyama, who heads the plaintiffs, said he worried his pancreatic cyst may become cancerous because his mother, who was at a location just 7 kilometers (4.2 miles) from ground zero, died of pancreatic cancer. He also said many of his peers suffered discrimination at school, work and elsewhere, like their parents.

Sakiyama said the ruling was “disappointing” but vowed to continue their campaign to win government support.