The earliest signs of dementia are rarely dramatic. They do not arrive as forgotten names or misplaced keys, but as changes so subtle they are almost impossible to notice: a slightly narrower vocabulary, less variation in description, a gentle flattening of language.

New research my colleagues and I conducted suggests that these changes may be detectable years before a formal diagnosis — and one of the clearest examples may lie hidden in the novels of Sir Terry Pratchett.

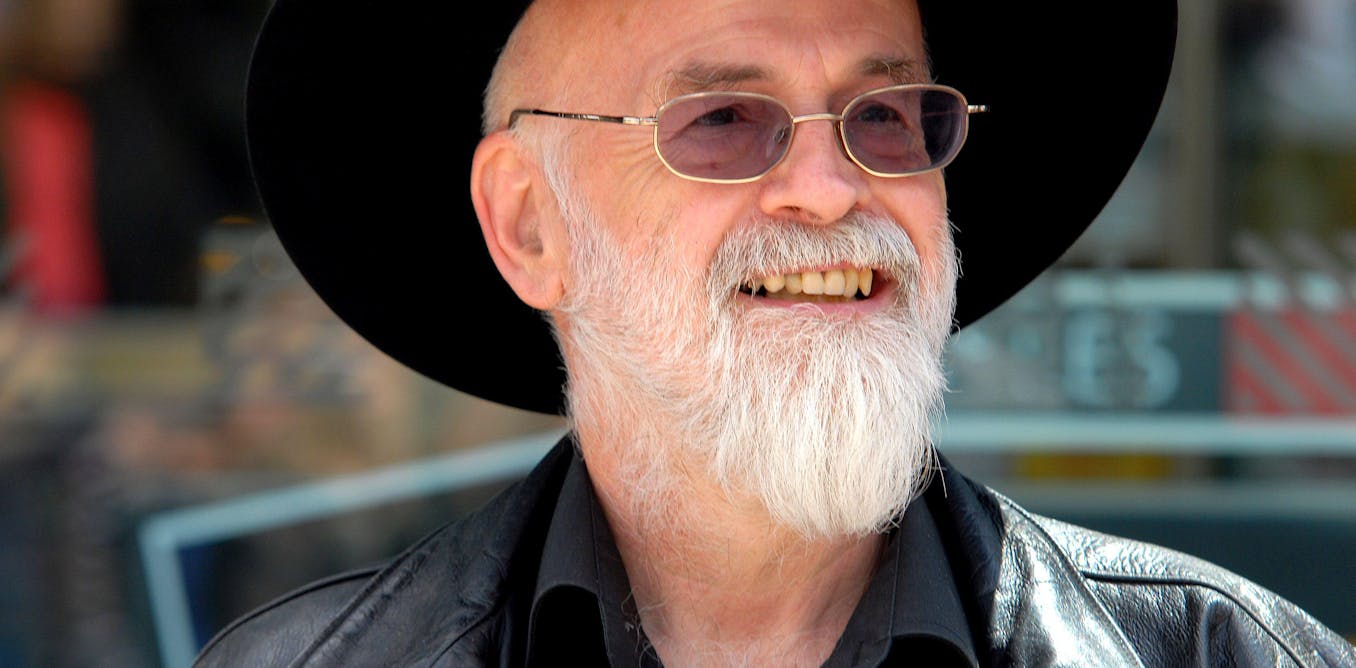

Pratchett is remembered as one of Britain’s most imaginative writers, the creator of the Discworld series and a master of satire whose work combined humour with sharp moral insight. Following his diagnosis of posterior cortical atrophy, a rare form of Alzheimer’s disease, he became a powerful advocate for dementia research and awareness. Less well known is that the early effects of the disease may already have been present in his writing long before he knew he was ill.

Dementia is often described as a condition of memory loss, but this is only part of the story. In its earliest stages, dementia can affect attention, perception and language before memory problems become obvious. These early changes are difficult to detect because they are gradual and easily mistaken for stress, ageing or normal variation in behaviour.

Language, however, offers a unique window into cognitive change. The words we choose, the variety of our vocabulary and the way we structure description are tightly linked to brain function. Even small shifts in language use may reflect underlying neurological change.

In our recent study, we analysed the language used across Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, examining how his writing evolved over time. We focused on “lexical diversity” — a measure of how varied an author’s word choices are — and paid particular attention to adjectives, the descriptive words that give prose its texture, colour and emotional depth.

Across Pratchett’s later novels, there was a clear and statistically significant decline in the diversity of adjectives he used. The richness of descriptive language gradually narrowed. This was not something a reader would necessarily notice, nor did it reflect a sudden deterioration in quality. Instead, it was a subtle, progressive change detectable only through detailed linguistic analysis.

Crucially, the first significant drop appeared in The Last Continent, published almost ten years before Pratchett received his formal diagnosis. This suggests that the “preclinical phase” of dementia — the period during which disease-related changes are already occurring in the brain — may have begun many years earlier, without obvious outward symptoms.

This finding has implications that extend far beyond literary analysis. Dementia is known to have a long preclinical phase, during which opportunities for early intervention are greatest. Yet identifying people during this window remains one of the biggest challenges in dementia care.

Linguistic analysis is not a diagnostic tool in itself, and it would not work equally well for everyone. Factors such as education, profession, writing habits and linguistic background all influence how people use language. But as part of a broader approach — alongside cognitive tests, brain imaging and biological markers — language analysis could help detect early risk in a non-invasive and cost-effective way.

Importantly, language data already exists. People generate vast amounts of written material through emails, reports, messages and online communication. With appropriate safeguards for privacy and consent, subtle changes in writing style could one day help flag early cognitive decline long before daily functioning is affected.

Why early detection matters

Early detection matters more than ever. In recent years, new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease have emerged that aim to slow disease progression rather than simply manage symptoms. Drugs such as lecanemab and donanemab target amyloid proteins that accumulate in the brain and are thought to play an important role in the disease. Clinical trials suggest these treatments would be most effective when given early, before significant neuronal damage has occurred.

Identifying people during the preclinical phase would allow people and their families more time to plan, access support and consider interventions that may help slow progression. These may include lifestyle changes, cognitive stimulation and, increasingly, new drugs to slow the disease progression.

More than a decade after his death, Terry Pratchett continues to contribute to our understanding of dementia. His novels remain deeply loved, but hidden within them is another legacy: evidence that dementia may leave its mark long before it announces itself. Paying closer attention to language — even language we think we know well — could help transform how we detect, understand and ultimately treat this devastating condition.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.