Standing on the hills looking out across flat green fields, linked by a network of hedgerows, copses and small settlements, the Somerset Levels looks like quintessential English countryside.

But this region’s rivers, drains, waterways and wetlands are integral to the levels’ history – an inhospitable, and at times perilously flooded, watery world, centuries ago only habitable during the summer months.

Right now, the levels are experiencing extensive flooding, stretching for miles on all sides of any roads that are still open to vehicles. Communities are trying to cope with a relentlessly wet winter halting transport, closing schools and leaving homes underwater, underpinned by a longer-term cycle of climate and sea-level change.

This part of south-west England, much of which is currently under water, used to be known as the “land of the summer people”. Historically, frequent flooding was the main reason for purely seasonal occupation in this area bordered by the Bristol Channel and the Mendip, Quantock and Blackdown Hills. Drier summers provided valuable grazing land and plentiful resources such as fish, peat, wildfowl and reeds, while the winter months brought heavy rain and floods, forcing communities to retreat to higher ground.

The climate here, although often wet, remained broadly similar to the rest of south-west England where year-round living was commonplace. So what exactly makes the Somerset Levels so prone to flooding and why does that matter now? The answer lies in its physical geography and how water from the sea, rivers, ice and rainfall has shaped the land over time.

Let’s go back to the end of the last ice age around 10,000 years ago. Although not under ice sheets directly, the river valleys of the Somerset Levels were inundated as the glaciers melted and sea levels rose. Dry land was only found on the nearby Polden Hills and on odd humps and mounds that rose as islands amid the sea – Glastonbury Tor is perhaps the most famous in today’s landscape.

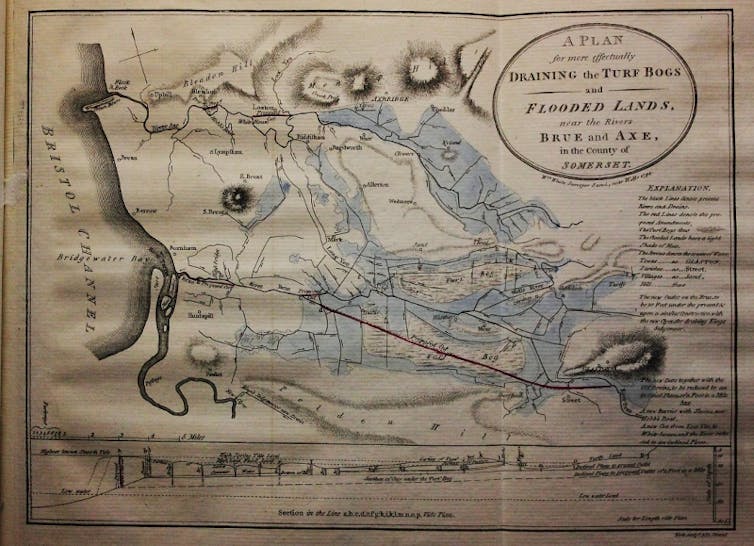

South West Heritage Trust, CC BY-NC-ND

It is these hills and islands that provided safe winter havens for local people. Over the following thousands of years, the sea retreated and advanced periodically, first exposing, then flooding, the low-lying land. Wetter periods were driven by a cooler and rainier climate, increased river flows, rising sea levels and overall slow sinking of the land as a result of “isostatic readjustment” – the balancing of southern England after the weight of ice lifted at the end of the last ice age.

In response to the changes, the environment shifted from marine to brackish and freshwater conditions, initiating the formation of peat bogs as plants died in oxygen-less underwater conditions.

By the Neolithic period (4000BC-2300BC) the Somerset Levels were a vast area of freshwater wetlands and reed swamps. Human-made wooden trackways crossed the impassable reed swamps, linking the drier hills and islands upon which hunters and farmers set up base. The tracks, preserved today in the peat, point to organised use of the wetlands likely during the drier months.

Through the iron age, encroachment of the sea made much of the landscape wet again, yet evidence of semi-permanent occupation is present in the preserved lake villages, constructed on artificial foundations of timber, clay, and rubble.

Romans exploited the Somerset Levels for salt production by evaporating salt from the salt water using clay ponds (salterns) heated by peat fires.

Medieval settlers diverted the main rivers to create canal systems that helped to reduce winter flooding and reclaim agricultural land as described by in the authoritative book The Lost Islands of Somerset: Exploring A Unique Wetland Heritage. Throughout history, seasonal adaptation was the key to successful living.

Draining of the levels

Large-scale and coordinated drainage of the Somerset Levels began around the 12th century and brought about a gradual end to seasonal occupation. River embankments were constructed to reduce tidal flooding and sluices were built to manage water flow.

A criss-crossing network of drainage ditches (known as locally as rhynes) was created to carry water off the fields and into the rivers – many of these are still visible today and play a critical role in flood risk management. From the mid-18th century and into modern times, engineering such as pumps and dredging (the removal of silt, mud and vegetation from river channels) were introduced to maintain a balance between water levels and productive agricultural land.

Today, pumping remains essential to manage flood risk. Dredging, however, remains a politically contentious issue and is only used as a carefully considered method in certain places. While dredging can benefit local flood risk in the short term, the longer-term implications for nature, water quality, downstream flood risk and economic cost are now widely known.

Read more:

Britain’s relentless rain shows climate predictions playing out as expected

Nicksarebi/Flickr, CC BY

Today, communities have settled permanently across the Somerset Levels but the risks of living here are ever present. Rivers, many of which remain artificially modified, drain from the surrounding hills into the flat, low-lying bowl of the levels where the peat and clay soils are highly water retentive.

At times of high tide and heavy rain, tide lock, where the sea rises higher than the river level, prevents inland floodwaters from draining into the sea. This causes water to back up, overwhelming pumps and exacerbating flooding. The climate is changing – for every 1°C of warming the atmosphere can hold around 7% more moisture, increasing the risk of extreme rainfall and flooding.

Future flood risk management will continue to combine traditional engineering with more natural processes. Measures such as developing flood storage areas, wetland creation, leaky barriers, woodland planting and changing how land is farmed help intercept and slow water flow, alongside the use of pumps, drains and sluices.

However, the devastating floods of 2013-14, were a stark reminder that not so long ago, the levels were the land of the summer people. As flooding takes hold again in February 2026, it’s not clear how long year-round occupation will remain viable on the Somerset Levels.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Jess Neumann works at the University of Reading as an associate professor of hydrology. She is a trustee of River Mole River Watch, a water quality charity who work with, advise, and receive funding from environmental and conservation organisations and agencies, water companies, commercial services, local authorities and community groups.