Scientists are calling for urgent action on free-living amoebas – a little-known group of microbes that could pose a growing global health threat. Here’s what you need to know.

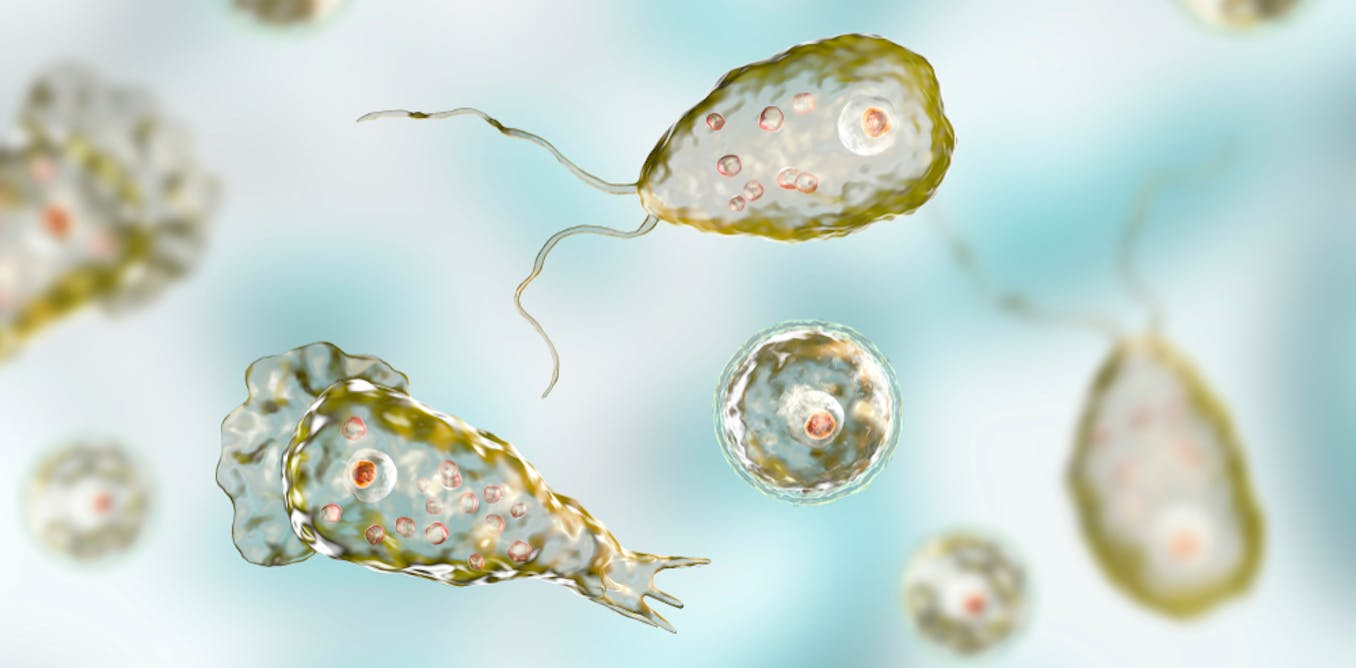

Free-living amoebas are single-celled organisms that don’t need a host to live. They are found in soil and water, from puddles to lakes.

What makes them remarkable is their ability to change shape and move using temporary arm-like extensions called pseudopodia – literally “false feet”. This allows them to thrive in an astonishing range of environments.

What is the ‘brain-eating amoeba’ and how dangerous is it?

The most notorious free-living amoeba is Naegleria fowleri, commonly known as the “brain-eating amoeba”. It lives naturally in warm freshwater, typically between 30°C and 40°C – lakes, rivers and hot springs. But it is rarely found in temperate countries such as the UK, due to the cold weather.

The infection happens when contaminated water enters through the nose, usually while swimming. From there, the amoeba travels along the nasal passages to the brain, where it destroys brain tissue. The outcome is usually devastating, with a mortality rate of 95%-99%.

Occasionally, Naegleria fowleri has been found in tap water, particularly when it’s warm and hasn’t been properly chlorinated. Some people have become infected while using contaminated tap water to rinse their sinuses for religious or health reasons.

Fortunately, you cannot get infected by drinking contaminated water, and the infection doesn’t spread from person to person.

Zaruna/Shutterstock.com

Why are these amoebas so difficult to kill?

Brain-eating amoebas can be killed by proper water treatment and chlorination. But eliminating them from water systems isn’t always straightforward.

When they attach to biofilms – communities of microorganisms that form inside pipes – disinfectants like chlorine struggle to reach them, and organic matter can reduce the disinfectants’ effectiveness.

The amoeba can also survive warm temperatures by forming “cysts” – hard protective shells – making it harder to control in water networks, especially during summer or in poorly maintained systems.

What is the ‘Trojan-horse effect’ and why does it matter?

Free-living amoebas aren’t just dangerous on their own. They can also act as living shields for other harmful microbes, protecting them from environmental stress and disinfection.

While amoebas normally feed on bacteria, fungi and viruses, some bacteria – like Mycobacterium tuberculosis (which causes TB) and Legionella pneumophila (which causes legionnaires’ disease) – have evolved to survive and multiply inside them. This helps these pathogens survive longer and potentially become more dangerous.

Amoebas also shelter fungi such as Cryptococcus neoformans, which can cause fungal meningitis. It can also shelter viruses, such as human norovirus and adenovirus, which cause respiratory, eye and gastrointestinal infections.

By protecting these pathogens, amoebas help them survive longer in water and soil, and may even help spread antibiotic resistance.

How is climate change making the problem worse?

Climate change is probably making the threat from free-living amoebas worse by creating more favourable conditions for their growth.

Naegleria fowleri thrives in warm freshwater. As global temperatures rise, the habitable zone for these heat-loving amoebas has expanded into regions that were previously too cool. This potentially exposes more people to them through recreational water use.

Several recent outbreaks linked to recreational water exposure have already raised public concern in multiple countries. These climate-driven changes – warmer waters, longer warm seasons, and increased human contact with water – make controlling the risks more difficult than ever before.

Are our water systems adequately checked for these organisms?

Most water systems are not routinely checked for free-living amoebas. The organisms are rare, can hide in biofilms or sediments, and require specialised tests to detect, making routine monitoring expensive and technically challenging.

Instead, water safety relies on proper chlorination, maintaining disinfectant levels, and flushing systems regularly, rather than testing directly for the amoeba. While some guidance exists for high-risk areas, widespread monitoring is not standard practice.

Beyond brain infections, what other health risks do these amoebas pose?

Free-living amoebas aren’t just a threat to the brain. They can cause painful eye infections, particularly in contact lens users, skin lesions in people with weakened immune systems, and rare but serious systemic infections affecting organs such as the lungs, liver and kidneys.

What’s being done to address this threat?

Free-living amoebas such as Naegleria fowleri are rare but can be deadly, so prevention is crucial. These organisms don’t fit neatly into either medical or environmental categories – they span both, requiring a holistic approach that links environmental surveillance, water management, and clinical awareness to reduce risk.

Environmental change, gaps in water treatment and expanding habitats make monitoring – and clear communication of risk – more important than ever.

Keeping water systems properly chlorinated, flushing hot water systems, and following safe recreational water and contact lens hygiene guidelines all help reduce the chance of infection. Meanwhile, researchers continue to improve detection methods and doctors work to recognise cases early.

Should people be worried about their tap water or going swimming?

People cannot get infected with free-living amoebas like Naegleria fowleri by drinking water, even if it contains the organism. Infection occurs only when contaminated water enters the nose, allowing the amoeba to reach the brain. Swallowing the water poses no risk because the amoeba cannot survive or invade through the digestive tract.

The risk from swimming in well-maintained pools or treated water is extremely low. The danger comes from warm, untreated freshwater, particularly during hot weather.

What can people do to protect themselves?

People can protect themselves from free-living amoebas by reducing exposure to warm, stagnant water. Simple steps include avoiding putting your head underwater in lakes or rivers during hot weather, using nose clips when swimming, choosing well-maintained pools, and keeping home water systems properly flushed and heated.

Contact lens users should follow strict hygiene and never rinse lenses with tap water. For nasal rinsing, only use sterile, distilled, or previously boiled water.

Awareness is key. If you develop a severe headache, fever, nausea, or stiff neck after freshwater exposure, seek medical attention immediately – early treatment is critical.

![]()

Manal Mohammed does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.