The western US is a geologists’ dream, home to the Rocky Mountains, the Grand Canyon, active volcanoes and striking sandstone arches. But one landform simply doesn’t make sense.

Rivers normally flow around barriers. The Danube river, for example, flows between the Alps and the Carpathians, twisting and turning to avoid the mountains.

But in north-western Colorado, one river does the opposite.

The intimidatingly named Gates of Lodore marks the entrance to the 700-metre deep Canyon of Lodore that slices straight through the Uinta Mountains as if the range wasn’t there at all. It was created by the Green River, the largest tributary of the Colorado River (of Grand Canyon fame).

For more than 150 years, geologists have debated why the Green River chose such an unusual path, creating a spectacular canyon in the process.

Eric Poulin / shutterstock

In 1876, John Wesley Powell, a legendary explorer and geologist contemplated this question. Powell hypothesised that the river didn’t cut through the mountain, but instead flowed over this route before the range existed. The river must have simply maintained its course as the mountains grew, carving the canyon in the process.

Unfortunately, geological evidence shows this cannot be the case. The Uinta Mountains formed around 50 million years ago, but we know that the Green River has only been following this route for less than 8 million years. As a result, geologists have been forced to seek alternative explanations.

And it seems the answer lies far below the surface.

Drip drip

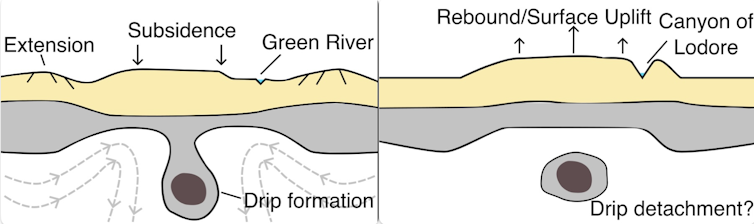

Colleagues and I have found evidence for a process in which part of the Earth’s crust becomes so dense that it begins to sink into the mantle beneath it. This phenomenon, known as a “lithospheric drip”, occurs deep in the Earth, but can have profound effects on the surface.

Drips often form beneath mountain ranges. The sheer weight of the mountains raise temperatures and pressures at the base of the crust, causing dense minerals to form. As these minerals accumulate, the lower crust can become heavier than the mantle it “floats” on. At this point, the crust begins to detach, or “drip”, into the mantle.

Smith et al (2026)

At the surface, this causes two things. Initially as the drip forms, it pulls the crust down, lowering the height of the mountain range above. Then as the drip detaches, the crust springs or rebounds back. The whole process is like pulling a trampoline down and then letting it go again.

For the Green River, this temporary lowering of the Uinta Mountains appears to have removed a critical barrier. The river was able to cross the range during this low period, and then, as the range rebounded, it carved the Canyon of Lodore as it continued on its new course.

A geological bullseye

Our evidence for the lithospheric drip comes from the river networks around the Uinta Mountains. Rivers record a record of past changes to landscapes, which geomorphologists can use to assess how the elevation of a mountain range may have changed in the distant past. The rivers around the Uintas show that the range had recently (in geological terms) undergone a phase of renewed uplift.

By modelling these river networks, we were able to map out the uplift. The result was striking: a bullseye-shaped pattern, with the greatest uplift at the centre of the mountain range, with things decreasing further from the centre. Around the world, this same pattern represents the telltale sign of a lithospheric drip. Similar signals have been identified in places such as the Central Anatolian Plateau in Turkey, as well as closer to the Uinta Mountains on the Colorado Plateau or the Sierra Nevada of California.

To test whether such a process was occurring beneath the Uintas, we turned to seismic tomography. This technique is similar to a medical CT (computerised tomography) scan: instead of using X-rays, geophysicists analyse seismic waves from earthquakes to infer the structure of the deep earth.

Existing seismic imaging reveals a cold, round anomaly more than a hundred miles below the surface of the Uintas. We interpreted this huge feature, some 30-60 miles across, as our broken-off section of the drip.

By estimating the velocity of the sinking drip, we calculated it had detached between 2 and 5 million years ago. This timing matches the uplift inferred from nearby rivers and, crucially, perfectly matches separate geological estimates for when the Green River crossed the Uinta Mountains and joined the Colorado River.

Taken together, these different bits of evidence point towards a lithospheric drip being the trigger that allowed the Green River to flow over the Uintas, resolving a 150-year-old debate.

A pivotal moment in the history of North America

When the Green River carved through the Uinta Mountains, it fundamentally changed the landscape of North America. Rather than flowing eastwards into the Mississippi, it became a tributary of the Colorado River, and its waters were redirected to the Pacific.

This rerouting altered the continental divide, the line that divides North American river systems that flow into the Atlantic from those that flow into the Pacific. In doing so, it created new boundaries and connections for wildlife and ecosystems.

The story of the Green River shows that processes deep within the Earth can have profound impacts for life on the surface. Over geological timescales, movements of country-sized lumps of minerals many miles below the surface can reshape mountains, redirect rivers and ultimately influence life itself.

![]()

Adam Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.