Olivia Vought, University of Michigan, discusses her article: Earlier snowmelt increases the strength of the carbon sink in montane meadows unequally across the growing season

In cold, mountain regions, the climate is warming, causing snow to melt earlier. In fact, winters are changing faster than the warmer seasons in many seasonally cold places. However, how these changing winter processes are cascading to influence ecosystems is still relatively unknown. In snow-covered, high-elevation places, snowmelt timing is critical for determining the length of the growing season. However, whether earlier snowmelt will cause plants to start growing earlier and increase overall carbon uptake or just shift the growing season earlier and not change overall carbon uptake, remains uncertain. If plants start growing earlier, they could maintain the same length of growing season if they have a fixed length of growth that ends after seed set, or if earlier snowmelt causes additional soil drying and decreased plant growth later in the growing season. Determining how the growing season length shifts in response to earlier snowmelt is important for understanding carbon cycling in response to a changing climate.

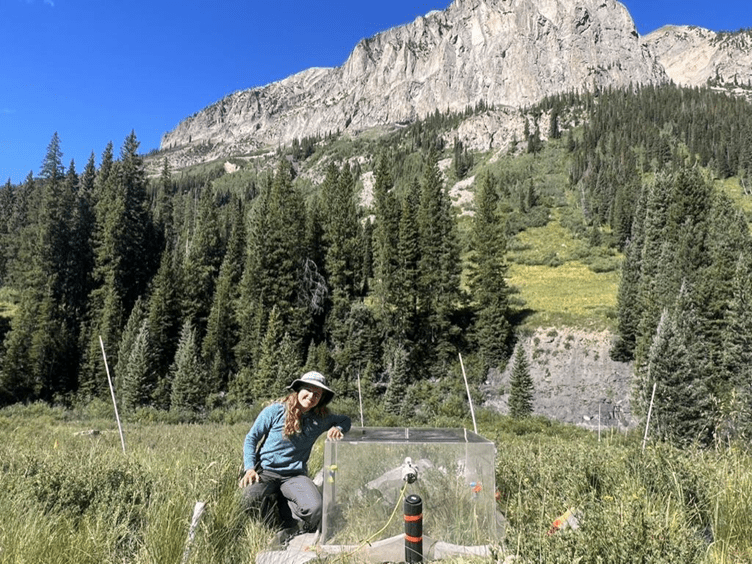

To determine the impact of earlier snowmelt on carbon cycling, we established an experiment near the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Western Colorado. We covered the experimental plots with black shade cloths, decreasing the albedo and causing the snow to melt approximately 12 days earlier.

The experimental setup: putting the black shade cloths on (left) and the completed experimental plots (right). Photo credit: Sophia Todorov.

In the earlier snowmelt plots, the snow melted away on May 16th on average, and on May 28th, on average, in the control plots. Starting in early June, we measured carbon fluxes and plant biomass in each of the plots biweekly. We assessed how gross primary productivity (GPP), ecosystem respiration (ER), and net ecosystem exchange (NEE) changed with earlier snow melt. NEE is the balance between GPP and ER and measures the strength of the carbon sink. We were curious whether earlier snowmelt changed the overall strength of the carbon sink.

To scale the five NEE measurements to a whole growing season assessment of carbon dynamics, we built a model that associated each of our in-field measurements with frequently measured data in the plots: soil moisture, air temperature, and light intensity. We then used the model to calculate cumulative NEE in the early, mid, and late parts of the growing season and summed the early, mid, and late season values to determine how earlier snowmelt impacted cumulative NEE across the whole growing season. We found that, on average, earlier snowmelt increased the strength of the carbon sink, with earlier snowmelt plots having greater carbon accumulation in the early and mid-season. Interestingly, this trend reversed in the later part of the growing season, with earlier snowmelt plots being a weaker carbon sink. This suggests that the growing season might be shifted earlier in the year with earlier snowmelt.

By identifying the pattern of carbon uptake in response to earlier snowmelt, we are helping to clarify one of the main questions regarding carbon management: will climate change result in more productive plant communities in cold places, or will productivity be offset by other limiting abiotic conditions? Here, we found that earlier snowmelt resulted in plots being stronger carbon sinks overall, with increased graminoid biomass in the early season helping to drive carbon uptake. However, with the shifting timing of the growing season, it will be increasingly important to understand how earlier growth and senescence are impacting species interactions.