The TV series Alien:Earth has introduced a number of new creatures to the much loved, albeit terrifying, Alien franchise.

But how realistic are the new aliens? That’s a question that we – a trio of scientists who are also great fans of the franchise and show – have tried to tackle with a ranking. To be clear, we are not trying to find flaws in the show. Like many fans we are simply having fun using science to analyse the creatures.

All species in the series draw inspiration from real living organisms and processes seen on Earth, but crank it up to the extreme. We therefore won’t explore all those parallels, but instead focus on how plausible the organisms are in terms of underlying processes such as physics, chemistry, metabolism and evolution.

1. The tick

Our most plausible creature is the large blood-sucking tick. On Earth, the deer tick Ixodes do swell to the size of a walnut when feeding, which is not too different from the Alien:Earth tick. In the show, we see it attack the jugular and quickly take on a couple of pints of blood.

The perhaps surprisingly quick death of the unfortunate prey most likely results from hemorrhagic shock due to how quickly the blood is lost. It is possible that some sort of chemical agent (perhaps an anticoagulant, as has repeatedly evolved in blood predators on Earth) is also injected. We do see a defence mechanism in episode five where the ticks release an airborne toxin to prevent them being removed from their host. Chemical defences like poisons and venom are common in animals and plants on Earth to deter predators.

In later episodes, we see it break containment (with the help of another alien) but we’ll assume it is simply seeking a body of water to lay its tadpoles in, rather than exhibiting intelligence. Horrifically, we see nothing that completely prohibits a life form like this.

2. D. plumbicare (the plant pod)

This creature, which as discovered and named in the show by the crew of the USCSS Maginot, benefits from not having been seen much (at the stage of writing, we have viewed the first six episodes). As the series progresses, it could move down our list. Initially, the character Kirsh questions whether it is flora or fauna. The science officer’s analysis ultimately shows they classify it as a carnivorous plant. Its green colour could indicate it also uses chlorophyll the way photosynthetic organisms like plants do on Earth.

Youtube, CC BY-SA

However, a near spherical body is in fact the worst structure for photosynthesis. It lacks any of the surface area enhancing adaptations you’d expect from a photosynthetic organism, such as leaves. This would be particularly important given it appears to hang underneath covering structures like cave roofs. Perhaps this is why it needs to capture prey: rather than evolving more efficient light capturing mechanisms, it instead alternates between photosynthesis and predation, depending on the resources available.

This is known as mixotrophy in science, but is a feature only of single-cell organisms on Earth. “Carnivorous” plants are not mixotrophs as they merely source compounds like nitrates, potassium and phosphorus from captured insects, rather than carbohydrates. Animals are heterotrophic, meaning they get energy by consuming other organisms.

Some organisms, such as corals, have bacterial symbiotes – “friendly” parasites – that can photosynthesise energy for them from the sun, which could be the case here.

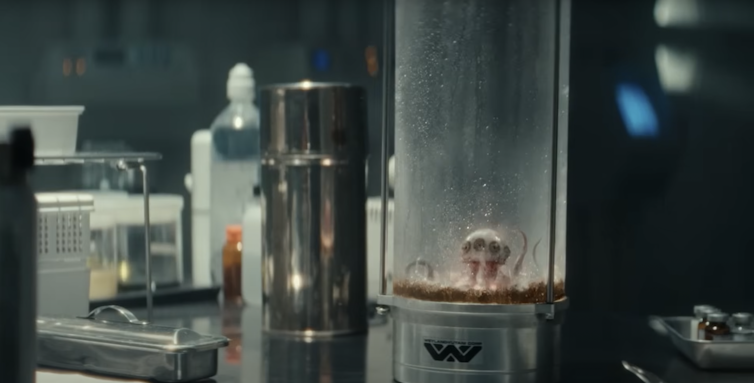

3. Trypanohyncha ocellus

T. ocellus is the lovable little eyeball octopus parasite. It attacks its host, removing an eyeball and then takes over entirely via connections to the brain.

youtube, CC BY-SA

This may seem like pure science fiction, but there are parasites on Earth that replace body parts and even control their host’s behaviour. However, the latter are usually relatively simple organisms, like the Ophiocordyceps fungus where taking over the brain of another animal is a necessary part of their life cycle. The behavioural changes these parasites induce are simple, such as moving the host towards light, water or the scent of a predator.

Toxoplasma gondii, for example, is a parasite that alters the behaviour of mice, making them less avoidant of the smell of cat urine. The infected mice are therefore more likely to be eaten by cats, which then spread long-lasting parasite spores in their faeces.

T. ocellus, in contrast, is very mobile, highly intelligent and strong, showing behaviour like monitoring situations and distracting humans. This behaviour is plausible with distributed ganglia (clusters of nerve cells) in the tentacles, similar to octopuses.

The length of these tentacles, however, exceeds that of similar structures on Earth, such as chameleon tongues, and is therefore somewhat implausible (but nevertheless incredibly cool). Our main issue here is why it needs to be parasitic at all – this is ultimately a formidable life form without requiring that.

4. The fly

First seen in episode 6, the fly appears to consume metal and metal ores and it pre-digests its food by spitting an enzyme, similar to flies on earth. Our main issue with it is that it’s unclear whether this is a supplement (such as iron and other trace elements in our diet) or a main energy source.

There is a process on Earth known as chemolithotrophy (literally “rock eating”) in which energy and biomass production can be harnessed by oxidation (removal of electrons from) of geochemicals – including iron, manganese and other metals.

On Earth, this is exclusive to single celled archea such as Ferroplasma and bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus, organisms generally associated with very slow growth. Multicellularity is energetically demanding, not to mention flying, meaning metal oxidation is not a very plausible energy source for the fly.

Of course, the metal could simply be a supplement, albeit a very large one, needed to create a metallic shell. Biomineralisation of iron compounds into the teeth of marine molluscs like chitons and limpets, who need hard teeth graze on rocky surfaces, is well documented.

A similar mechanism could explain the hard metals in the Xenomorph’s exoskeleton (which it needs to be able to scratch through the metal in a ship’s hull).

5. The Xenomorph

The Xenomorph might come in at the bottom of this plausibility ranking, but it takes the top spot in our hearts/chests. The main problem with it is its impossibly fast growth rate, transitioning from a relatively small chest-burster to a fully grown adult in a very short period of time.

Youtube, CC BY-SA

Very crudely, if we assume it has a similar metabolic efficiency to humans, and that it weighs roughly 100 kg, then it would need to consume and convert millions of calories of food (over a tonne of pork-like meat) in what seems to be a few days at most. Of course, it could have a much higher metabolic efficiency than humans, though it would always be bound by the conservation of mass and energy. You can’t acquire more biomass than you consume. And we never see it eat, not even its initial host.

Circumventing this would require an ultradense (entirely hypothetical) energy source that it carries with it from the egg (Ovomorph). But energy has to enter the system at some point, implying the Queen would have to eat or capture huge amounts of energy somehow.

Another issue for the Xenomorph is that, if it did need to eat the huge amount of creatures it kills, it would rapidly deplete any prey resource and there would probably be no stable ecosystem that could support it. However, in the expanded universe, it seems that the Xenomorphs are artificial beings, created from a bio-weapon intended to obliterate an ecosystem, leaving a clean slate. In which case, they seem very effective.

![]()

Thomas Haworth receives funding from The Royal Society and UKRI.

Jen Bright receives funding from BBSRC

Chris Duffy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.