Many financial and political analysts are trying to assess the impact of President Donald Trump’s decision to fire U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Commissioner Erika McEntarfer on Aug. 1, 2025, the same day that an unemployment report conveyed weakness in the job market. Some of the strongest criticism of this unprecedented move has come from Republican-aligned and nonpartisan experts, including a former BLS commissioner Trump appointed during his first term and the American Economic Association, a nonprofit that has 17,000 members in academic, government and business professions. They have said that what Trump has accused McEntarfer of doing – “rigging” data“ – would be impossible to pull off.

The Conversation U.S. asked Tom Stapleford, a professor who has written a book on the political history of the U.S. consumer price index, to explain why this move could undermine trust in the indicators the government releases and why that could damage the economy.

What key data does the BLS release?

Founded in 1884, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes monthly and annual data about American consumers and workers. Historically, the BLS has focused on urban workers and consumers, while the Department of Agriculture covered farmers and agricultural work. But these days, the Bureau of Labor Statistics also collects some data reflecting rural areas too.

The bureau publishes monthly data on inflation, employment and unemployment, and compensation. It also measures productivity on a quarterly basis, and twice per year it issues reports on consumer purchases – what people buy and how much they spend in different categories.

These official statistics are often revised in the months that follow as the bureau adopts new methods or more data becomes available.

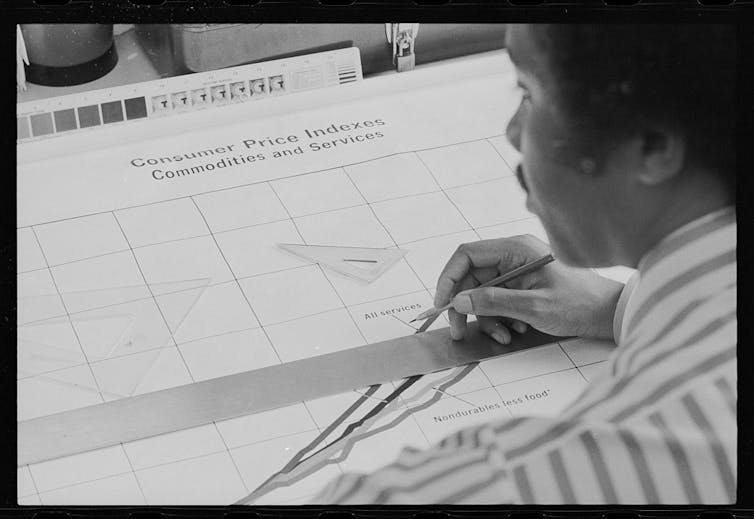

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

How can data affect markets and the economy?

The bureau’s data on inflation, employment, unemployment and compensation draws the most attention because it answers basic questions about the economy.

For example: Are prices rising? Are employers adding new jobs? Are people finding work? How much are workers getting paid?

Employment and unemployment may seem very similar, but they show you different things. BLS employment data tells you how many jobs there are, where they are and in what lines of work.

BLS unemployment data is about people. How many Americans are looking for work but can’t find a job? How many have part-time jobs but would prefer to work full time?

The BLS also collects, analyzes and releases inflation data that shows how price changes are affecting American consumers. The BLS consumer price index data is weighted so that changes in the prices of items that are a big part of household expenses will have a larger effect on the final results than other changes.

Each BLS statistic has a narrow focus, but, taken together, they can reveal a lot about economic conditions across the country and in specific states.

Businesses and investors look to BLS data as guides for trends that might affect companies or financial markets as a whole. If prices start to rise quickly, the Federal Reserve might raise interest rates, which reduces bond prices.

If job creation starts to slow, the country might be heading toward a recession, and employers might pull back on hiring and production or invest less in new equipment. Policymakers use BLS statistics to guide decisions about government actions, and everyone else may use them to judge whether politicians have succeeded in managing the economy well.

Of course, all of these uses depend on Americans being able to trust the numbers. The BLS goes to great lengths to secure that trust, publishing detailed descriptions of its methods and research papers that try to explain patterns in the data and test new approaches. Until recently, the BLS also had two unpaid advisory committees of economists and statisticians from companies, universities and nonprofits that analyzed BLS methods and offered advice.

However, the Department of Labor disbanded those committees in March 2025, stating that the committees “had fulfilled their intended purpose.”

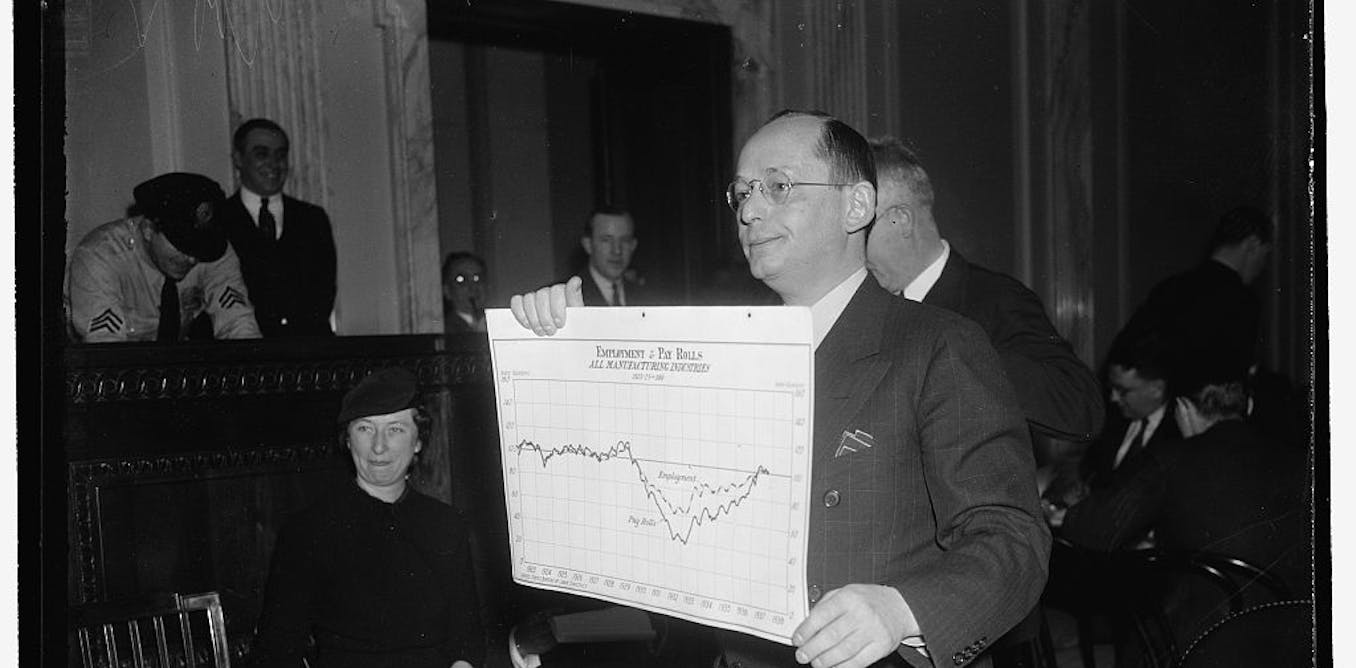

Library of Congress

What does the BLS commissioner do?

The BLS commissioner oversees all aspects of the bureau’s operations and serves as the primary liaison with Congress and the leadership of the Department of Labor.

Although some early BLS commissioners did not have advanced degrees, all commissioners since the 1930s have had Ph.D.s in economics or statistics, as well as substantial experience using or producing statistical data.

Unlike rank-and-file BLS staff, who are typically career civil servants, the commissioner is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate for a four-year term. Due to the timing of those terms, each commissioner’s tenure normally spans two presidential terms. The Senate overwhelmingly approved McEntarfer’s nomination, for example, in an 86-8 vote held in January 2024.

However, this appointment is at will, meaning that a president can legally remove a commissioner at any time.

Could the top BLS official fudge any data?

It would be very difficult for the commissioner to alter or falsify data on his or her own.

The data is produced collectively by a large nonpartisan staff who are protected by civil service regulations, so it would be impossible for the commissioner simply to change the numbers.

Nonetheless, the commissioner could shape BLS data indirectly. The commissioner could make certain data harder to access, devote fewer resources to some topics or close some data series altogether.

More significantly, creating national statistics is complicated: There is always uncertainty, and even experts will disagree on many issues. A sufficiently motivated commissioner could potentially nudge the data in favored directions simply by altering the methodology.

If BLS staff thought a commissioner was truly trying to manipulate the statistics, however, I would expect many of them would resign or protest publicly. And there’s no sign of that having happened under McEntarfer’s leadership. She has strong support from former BLS commissioners and leading economists.

What are some possible consequences?

I do not expect to see any immediate consequences from McEntarfer’s firing.

The acting commissioner of the BLS, William Wiatrowski, is a longtime BLS employee who has held this role before.

The rest of the bureau’s staff remain the same. Over the long term, the actions of whomever Trump appoints as McEntarfer’s permanent replacement will determine whether her firing was an aberration or the mark of a new relationship between the White House and the BLS that could eventually undercut trust in its statistics.

To strengthen confidence in the BLS, the new commissioner could reinstate the external advisory committees that the Trump administration has disbanded. But he or she could weaken confidence by making controversial changes, especially regarding employment statistics, that are criticized by leading professional organizations or that cause top BLS officials to quit their jobs.

I believe it’s unlikely that BLS statistics could be faked in ways that would deceive economists. But they could become much less useful, and that would be bad for the United States.